This week we look at another transit plan for Vancouver in the context of the freeway debates of the 1960s. Created by the British Columbia Research Council for the Department of Highways, Rail-Rapid Transit for Metropolitan Vancouver examined the feasibility of including a rail-rapid transit system as part of its plan for a freeway and bus rapid transit system.

This week we look at another transit plan for Vancouver in the context of the freeway debates of the 1960s. Created by the British Columbia Research Council for the Department of Highways, Rail-Rapid Transit for Metropolitan Vancouver examined the feasibility of including a rail-rapid transit system as part of its plan for a freeway and bus rapid transit system.

By John Calimente, re:place Magazine

The late 1950s and early 1960s were a time of massive freeway and bridge construction in the Lower Mainland, led by Minister of Highways Phil Gaglardi, in office from 1952 to 1968. In short order, the Oak Street Bridge (1957), George Massey Tunnel (1959), Ironworkers Memorial Bridge (1960), Upper Levels Highway (1960), freeway conversion of Highway 99 (1960), Annacis Island Bridge (1961), the Trans-Canada freeway through Burnaby (1963), and the Port Mann Bridge (1964) were completed. The freshly-built freeways encouraged new arrivals to live in the suburbs and commute to work, increasing traffic and causing transit mode share to drop. Automobiles dominated discussions of transportation at a time when average transit usage was dropping rapidly in Canada, from 220 rides per capita in 1945 to just 70 rides per capita in 1967. Vancouver’s city centre became congested with traffic during peak periods, as more people took to their cars. A Downtown Parking Corporation was proposed along with the widening of major arterials.

While Vancouver had grown into the third largest metropolitan region in the country, it comprised 10 separate municipalities with no governing body to create a regional transportation system (even the GVRD wasn’t created until 1967). The province took responsibility for highway building in eight of these municipalities, save for Vancouver and New Westminster, who were left to determine policy and finance construction on their own. In 1954, Vancouver established the Technical Committee for Metropolitan Planning, consisting of the City, surrounding municipalities, and the provincial government. It created the 1959 opus ‘Freeways with Rapid Transit’, that advocated for a $450 million master plan that would carve four freeways through Vancouver, converging downtown. The freeways would cut along the Arbutus Corridor from the south and along First Avenue from the east, to meet up in downtown Vancouver before crossing to the North Shore along the Lions Gate Bridge route.

The idea was that “freeway buses” would be utilized on these freeways to get commuters to and from work. An issue of BC Electric’s Buzzer from March 1959 featured on the Buzzer Blog promotes this plan. Rapid transit at the time meant buses on freeways, since according to Vancouver’s Director of Planning at the time, “the volume of rapid transit passengers would be insufficient to make a rail system practical.” Of course, they were assuming that only a small fraction of the population would choose to take public transit over the automobile. This was at a time when the metropolitan population of 650,000 was scattered over 10 municipalities, with about 370,000 in Vancouver.

It was into this milieu that Rail-Rapid Transit for Metropolitan Vancouver was created in 1962. As the huge cost of the 1959 freeway plan became clear, the Department of Highways commissioned the BC Research Council to study the feasibility of a rail-rapid transit system. However, it started with the flawed premise that freeways would be built through Vancouver, rather than rail transit substituting for freeways. The report states that the Highway Planning Committee had developed a plan “for a system of freeways, together with a bus-rapid transit system operating on the freeways, to meet the mass transportation requirements of the area”, but that the BC Department of Highways wanted to examine the feasibility of “including a rail-rapid transit system in the overall scheme.” As well, the report used the technical data from that 1959 freeway study, which had already concluded that commuter volumes would not be high enough for rail transit. But it still makes for interesting reading.

Its conclusions are laid out at the beginning of the report.

- Although no route justified rail rapid transit in 1962, “a short length from the central business district to Boundary Road can be considered by 1980.”

- There was “no evidence that the rail-rapid line would attract more passengers than a bus-rapid line on its own right-of-way.”

- On a positive note, it states that “subway trains would act as a downtown distributor facility and remove the need for elevated bus rights-of-way with bus stations or moving sidewalks.”

- The estimated number of transit passengers in 1980 leaving the Central Business District would be 17,650 at peak times, with 120,000 round-trip passengers on the average weekday.

- The total capital cost of a rail line to Boundary Road would be $71.7 million on its own private right-of-way, or $66.2 million in the median mall of “the proposed East-West freeway between Hastings and First Avenue.” If the line were located on the BC Electric Railway Company alignment further south, the cost would rise to $89 million.

- Looking at the lines with similar passenger volumes in Cleveland and Chicago, “the line east to Boundary Road is worth including in the detailed evaluation of the overall Vancouver plan.”

- A rail line south on the Arbutus alignment was not considered justifiable, even by 1980

- Rail transit at the First Narrows was not justifiable in the foreseeable future

- And finally, “Rail-rapid transit is not considered an economical means of transportation when transit densities are under 10,000 persons per peak-hour one-way.”

Two rail lines alignments were considered. The first was an east-west route to Boundary Road either between Hastings and 1st Avenue, or along this alignment only up to Victoria Drive, where it would join the BC Electric right-of-way. The report notes that if this alignment were used, “it allows for later extension to New Westminster (or further) if this should ever be required.” The other would be a north-south route along Arbutus, terminating at 41st Avenue. One assumes that there would have to be rather large bus loops constructed at the ends of these lines, but this is not mentioned in the report. Downtown stations would be located at Robson, Seymour, Cambie, and Main. Interestingly, these station locations are pretty much duplicated now on the Expo and Canada lines.

As for the freeway-bus, it would eventually require a terminal with grade-separated access streets or ramps. However, since there was no terminal location convenient for the whole of downtown, “an elevated bus-loop or moving sidewalks on structure at second-floor level have been suggested.” I guess walking around downtown hadn’t been invented yet. The report goes on to admit that for the freeway-bus system to work, “a system will have to be engineered for the CBD which has not been used in any other city.”

Rail-Rapid Transit for Metropolitan Vancouver was followed in 1964 by A Review of Transportation Plans, which regurgitated the findings of the 1959 and 1962 studies, as well as proposing a 20-year financial formula for freeways, funded by all three levels of government. The famous Vancouver Transportation Study of June 1967, with its proposals for a north-south freeway and and east-west freeway cutting through Chinatown, were met with huge public protests when city council approved its recommendations. Strange that city officials didn’t think that there would be any objection to a 9-metre high, 80-metre wide 8-lane freeway demolishing local neighbourhoods.

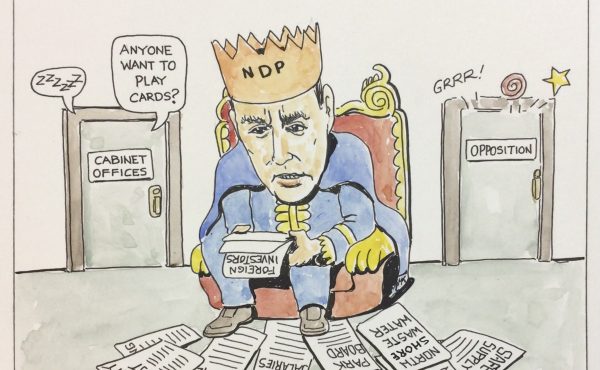

The announcement by Federal Transport Minister Paul Helleyer in October of 1967 that the federal government would not contribute towards any freeway construction in Vancouver was the beginning of the end of grandiose freeway plans for the city. While Vancouver city council approved in principle the design of a third crossing between the North Shore and downtown, Vancouver had trouble raising the $12.2 million necessary for approaches to the tunnel. The vote in December 1971 to spend $3.4 million on the approaches from general funding set off another round of protests, led by the Citizens’ Committee for Public Transit, which gathered 20,000 signatures on a petition for a plebiscite on the issue. The announcement in April of 1972 that the federal government was shelving the third crossing until after the federal election, as well as the election of the pro-transit TEAM council in Vancouver and the NDP in the provincial election three months later, spelled the end of freeway plans in Vancouver.

With all of the freeway proposals for Vancouver flying around between 1959 and 1972, it is truly remarkable that only the Georgia Viaduct was completed (although the Granville Bridge must have been built in 1954 with the assumption that it would eventually connect up to a freeway). Odds are that if the province had provided funding in the late 1950s or early 1960s, Vancouver would already have its downtown freeway. I didn’t find a definitive answer as to why only Vancouver and New Westminster were left to their own devices, but it’s clear that this was a big reason why they didn’t become like every other freeway plagued city in North America.

***

John Calimente is the president of Rail Integrated Developments. He supports great mass transit, cycling, walking, transit integrated developments, and non-automobile urban life. Click here to follow TheTransitFan on Twitter.