The Museum of Vancouver —through its Maraya Project—provided a rare glimpse of the behind-the-scenes world of international city building reflected over the time and geography of the works of designer-developer Stanley Kwok. Under discussion the evening of April 19 was the products and impacts of his career’s two defining, influential, and strikingly similar waterfront mega-projects: Vancouver’s North False Creek, and Dubai’s Emaar Marina.

What started off as a send up to the venerable city builder’s life, times and works, with co-presenter and local architecture critic Trevor Boddy, transformed into a discussion of the nature of city building itself and its effect on urban cultures.

Kwok’s projects have influenced the development of Vancouver since he emigrated from Shanghai and graduated from architecture at St. George College in Hong Kong. As an architect in Vancouver, Kwok rallied his connections to become one of the guiding forces on the restructuring of the redevelopment of the False Creek rail yards and the redevelopment that would eventually surround BC Place on the northern shores of False Creek.

False Creek as a development and planning project is one of the most influential on contemporary Vancouver. The community of podium and tower lots connected through development agreements to associated public amenities—such as the seawall, parks, and social housing —reflects how Vancouver is commonly branded as a development model.

Trevor Boddy has been a long time supporter of this model of city building, and speaks with reverence to Kwok’s works. For his part, Mr. Kwok regarded his works as effective projects within the context of their time: ones that should be viewed as “good or bad for the city” depending on the measure of success.

The Maraya (“mirror” in Arabic) Project at the Museum of Vancouver is exhibiting until May 20th 2012 and intends to provide a platform for reflection and debate about Vancouver’s urban culture.

Over the course of the discussion, Boddy emphasized the ability for a mirror to distort or clarify what is reflected. In response, Kwok accurately added “depending on how it is polished”.

The Maraya exhibit presents the two waterfronts in photograph and video form, as well as with an interactive online component that allows one to track, link, compare and contrast these similar urban landscapes. However, despite the parallels that can be drawn, the paths that led to each development as well as the contexts and systems within which they exist are as different as they are the same.

This being the case, it is worth looking more closely at both large-scale projects located 12,000km apart. In this feature, we will be examining the development of the North Shore of False Creek and Kwok’s roles in the process. The second part will focus on how Kwok and other Vancouver designers have impacted Emirati urban development and design.

The Development of False Creek North

Transpo86 “Exposition and BC Place”

Kwok’s impact on False Creek North is complex and multi-faceted. He managed to connect himself early in the redevelopment planning processes of the former Canadian Pacific Rail yards that became BC Place, The Expo lands, and later Concord Pacific. In the 1980s, Kwok worked as a liaison between the Chinatown community and the development teams before, during and after Expo ’86.

Sounding as though he still feels that this may have been a lost opportunity, Kwok described some of the original plans for BC Place as intending to be a “Downtown of the Province” and more than just a stadium site. With the construction of gaming and stadia developments as the primary commercial activity on the site, other urbane activities were not given the opportunity to flourish and engage the city in a meaningful way.

After Expo had ended, however, plans for the Exposition site changed direction and the Province looked at selling the site as a whole instead of administering the project piecemeal, as originally anticipated. At the time, Kwok was well in place with connections to—and discussions with—billionaire Li Ka-Shing. Li, with foresight for what was to come, was looking to invest outside of Hong Kong before the 1996 handover to China and was eventually able to purchase the entire North False Creek development site from the Province for a fraction of the land cost. He would would later transform the holding into Concord Pacific—one of the largest single urban redevelopments in North America.

The Lagoons “Blue Plan”

One of the early major planning exercises for False Creek North was the “Lagoons Plan”, that included artificial inlet lagoons separating islands of development from the structure of the downtown. This scheme proposed the development of an artificial waterfront on what is currently Pacific Boulevard. The plan, however, was criticized by reviewers and the public for having an “elitist” nature where tower clusters on islands were separated from the city by their moat-like inlets.

The Parks “Green Plan”

The “Green Plan” developed in response to criticism of the “Lagoons Plan” and transformed the water inlets into green after doing the water well testing; park open spaces that broke up the clusters of tower development while connecting them to one another other—and the downtown core—through a shared and accessible public amenity provided throughout the development. As seen in the image above, this plan closely resembles what was agreed upon and ultimately built.

Density In Question

The debate that has preoccupied and surrounded Vancouver developments, especially the mega-projects of False Creek, has been the introduction and appropriate placement of density. False Creek North provided a testing ground for a model of densification with amenity concessions to provide the recreation spaces as well as housing. The development is now the standard by which we look at the impacts of high-density living and developer contributions. It is the poster child of the Vancouverism.

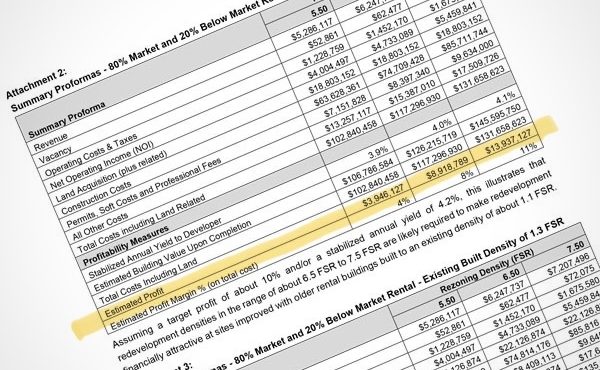

During the discussion, Kwok reiterated — as he stated during the early stages of the development to then Mayor Mike Harcourt — that no matter what the design outcomes of the North False Creek development were to be, the central rationale had to be maintained: “If the project can’t make money… it can’t be built in the first place.”

Kwok remembered a design gaming exercise he played with stakeholders in the site’s planning process, where he placed tiles representing units of residential space needed to reach the developments’ expected return on investment. The gaming allowed the stakeholders to alter the location of building height, “by chopping off the tops of stacks, but making sure that they were redistributed” elsewhere.

Kwok also talked about the tower-over-podium design that had become the hallmark for False Creek. He suggested the original intention was to have larger podiums with uses wrapped around a core of structured parking, instead of taking it below grade and waterline, at a much higher cost. However, with the City’s zoning policy, the floor plate of any level above ground parking would be counted towards the buildings’ total density, making it prohibitive to build in that way. This issue still affects nearby development sites, such as the Olympic Village and False Creek Flats.

Involving the Public

The project underwent a number of iterations and reviews – some counts were at 120 separate review, design panel, and public meetings. However, despite being considered by many to have been railroaded through the approvals process, for the size and scope of project that it was, North False Creek was grassroots in comparison to Kwok’s other waterfront mega-project. Dubai Marina had a single owner / developer for a site roughly the same size of False Creek in its developed entirety.

Comparatively, the review process was less publicly involved, as it had a grand total of zero public events and processes. The Emaar development company and the parent state agency was the sole stakeholder necessary in the Emirate. We’ll explore the design issues and outcomes of Dubai Marina next time and look at how Vancouver has impacted culture and development in the Middle East.

***

Join us for the second part of this In Depth Feature—Stanley Kwok and the Two False Creeks: Part Two – Mirrors, Mirages and Vancouverism in the Middle East— where we will examine how Kwok and other Vancouver designers have impacted Emirati urban development and design, as well as, how the process and outcomes reflects back on Vancouver.

**

Brendan Hurley is a local urban design planner who focuses on planning for adaptive neighbourhood change. His work has taken him around the world, but is strongly rooted in his native Vancouver. Living and working out of the heart of downtown, he remains keenly focused on the region’s development and history. Brendan is acting as Assistant Editor of Spacing Vancouver, but also consults as director of the UrbanCondition design collective.