![[re]Presenting Halifax](http://farm5.static.flickr.com/4138/4894951460_9fef579d4d_o.png)

![[Re]Presenting Halifax](http://spacing.ca/network/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/feature-representing-hfx-60.gif)

The [Re]Presenting Halifax series revisits historical and contemporary maps, diagrams and other interpretive readings of the Halifax region. See my first post for the full aims of this project and more information about contributing to the series.

HALIFAX – Halifax is well represented by the grid — a street pattern that is as symbolic of our British colonial past as the Citadel itself. And in many ways, the grid still serves us well today; the narrow blocks have contributed to Halifax having one of the country’s most walkable downtown cores despite it being situated on the side of steep hill.

But like any city, Halifax is not static nor immune to periods of growth, decay, destruction, [re]development and re-emergence. These natural processes of human settlement have produced a range of results – amputations, cancers, incisions, transplants and grafts in the urban tissue that both scar and reshape the city that we experience today. And depending on the resiliency of the system, the results can be immediate failure, slow decline or mutation. Throughout the life of the city, changes can extend or build on existing patterns, while others create notable exceptions to the surrounding ‘rules’.

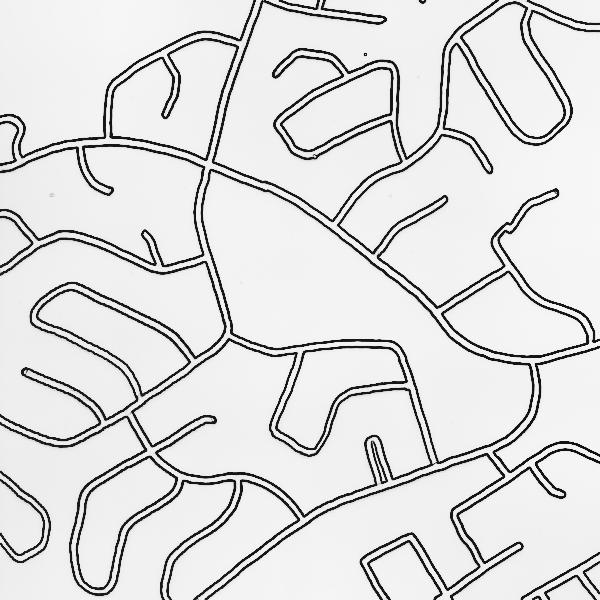

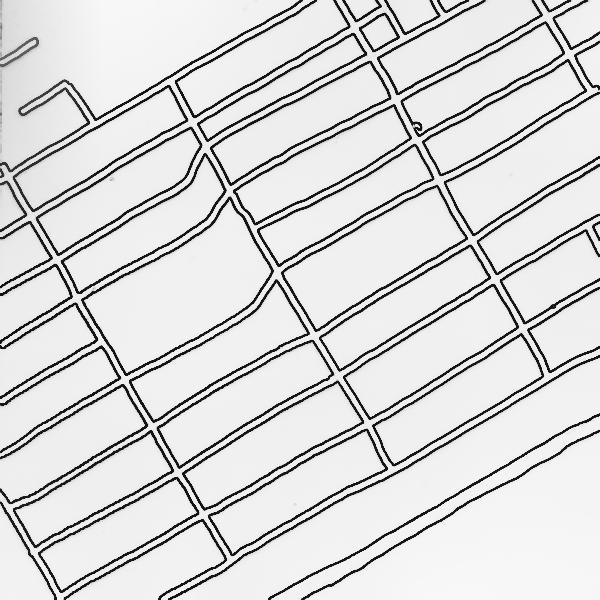

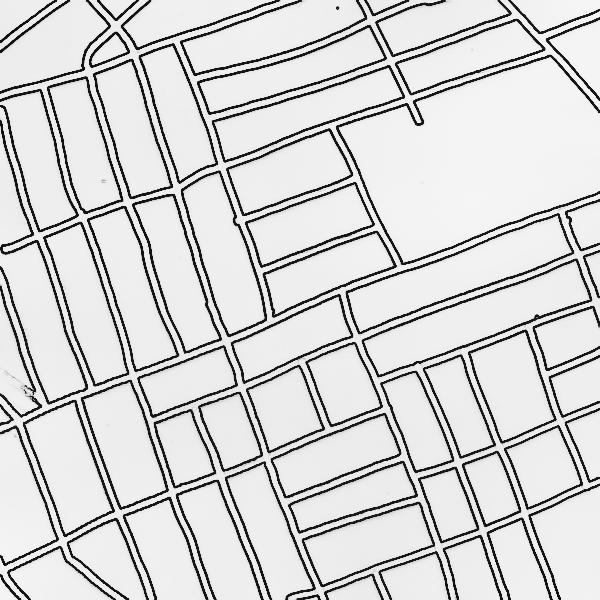

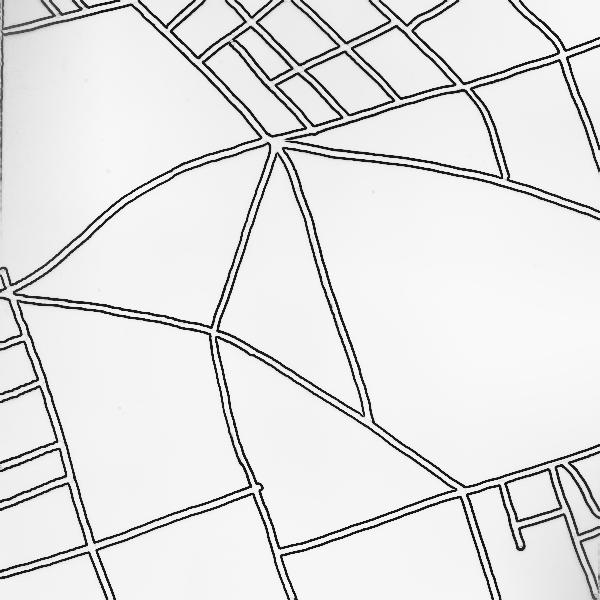

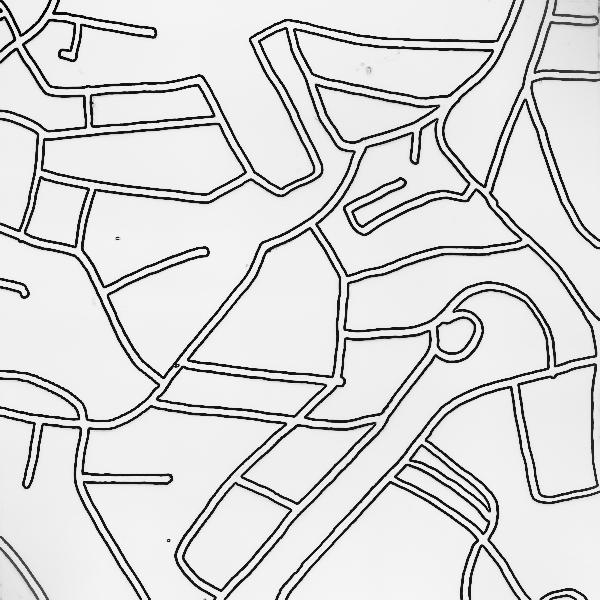

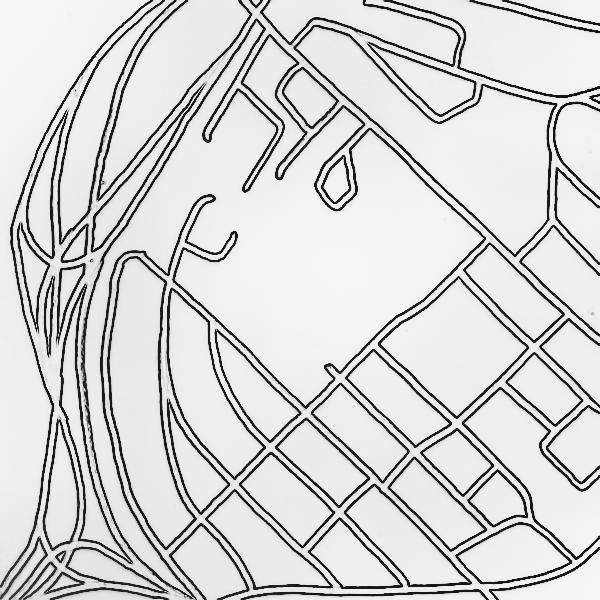

Presented below are a series of ‘tissue samples’ taken from the Halifax urban region. All are drawn at the same scale — each being one square kilometre extracted from the surrounding territory. They are simple representations of space, showing only the road structure, which —despite the region’s dominant natural topography — is arguably the main structuring element most often used in planning processes (along with other anthropogenic objects such as trunk sewers).

These simple, pseudo-schematic representations of the city can reveal both a ‘pattern language’ for Halifax, as well as numerous notable places of exception. For those who are most familiar with the street network and traverse these areas regularly, points of segregation, fragmentation, congestion may be evident from the street patterns themselves, while other points of activity and conflict may appear as nothing more than a point of intersection among many others.

For this reason, it is important to remember that this is but one layer purposefully extracted from all other contextual qualities. And while it may suggest the success of certain circulation patterns over others, it is but one piece of a much bigger and more complex picture. It begs the question: why do we continue to structure our city primarily through standard streets? Are other types of connective paths more appropriate and successful in creating urbanity?

Without making specific comments on the samples themselves, I would suggest that this is too often the way the city is described — a shallow analysis of something much deeper. Using only roads gives the impression of a high level of connectedness in each sample space, but the situation on the ground is often much different. How different would each sample space appear if represented with other spatial and social elements, relationships, phenomena? Knowing that most maps show only a fraction of the conditions present in the space, what are the most important layers when discussing the future of the city? In an urban context, is the road network still the best base layer from which to identify and project the future form on the city? If not roads, what other basic identifying or vital elements would you use to facilitate a conversation about the present condition and future potential of Halifax?

![[re]Presenting Halifax](http://farm5.static.flickr.com/4101/4894951340_bcabdded49_z.jpg)

4 comments

I’d kind of like to see a zoning map… like on Sim City. Also, a culture map would be pretty neat to plot out in Halifax.

Also, transportation infrastructure (not necessarily roads) should be the primary layer to project future city planning. Gotta get to your home/business somehow.

It would be interesting to compare the deacde in which each ’tissue sample’ was proposed or built. The lengthy history of the city has made it a veritable museum of city planning trends that are uniquely present in each of these well taken samples.

The ‘street’ network will continue to be the dominant structuring element of cities and the dominant transportation element as well, not just for cars but for pedestrians, bikes, buses, wheelchairs, streetcars, etc. Consider just how simple yet powerful the grid structure is, it still defines many old North American cities, even after momentous changes. Like Dustin pointed out street pattern and block size gives you powerful clues about when areas developed and what planning principles were popular at the time.

Where the ‘street’ network looses its dominant structuring role is when roads are built in place of streets – road which are exclusively or almost exclusively for the automobile. The spaghetti noodles in the North End map show what I mean. This isn’t a place, this is an on-ramp. This destroys instead of adds to the cities structure. I’d be interested to see what the pattern language of newer commercial areas like Bayer’s Lake or Dartmouth Crossing look like with only the streets shown. Again you would not see a place, but a spot without structure where automobiles happen to be stored.

Good comments.

While the street may remain dominent in existing pieces of the city, what about in new areas – emerging trends in landscape and ecological urbanism suggest a move toward landscape as the defining structuring system. If this is indeed the case, can or should natural features that have been long removed be reintroduced into the “old” city?

This difference between road and street is an interesting argument worthy of more discussion. People like A. Smithson, Van Eyck, etc. have been arguing since the 60s that we no longer understand what “the street” is and have repeatedly failed to create new streets. Their response were new building typologies such as mat-buildings and an emphasis on path based design. I would argue that one of the most important factors in creating streets is plot size/narrow street frontage. Rather than getting bogged down in discussions around density, perhaps we should be more concerned with intensity of use and mix – such as that which is achieved using a very narrow plot structure.

I think that looking at a place like Dartmouth Crossing we would actually see a highly structured and planned place – and it, instead, would be the plot structure that would look very unstructured due to their size and fragmentation. There is little continuity in building type, homogeneous programming, etc. But at the same time, I don’t think is trying or wants to be part of the city – it is something completely different and impossible to compare.