HALIFAX – Last week, Halifax Regional Council voted to ask the Province to grant the municipality the power to regulate political campaign donations in civic elections. It’s a wise move because Halifax’s elections are currently almost bereft of rules. The only requirement set by the province is for candidates to maintain a separate bank account for campaign funds and to disclose the identity of anyone who contributes more than $50. Other than that, there are no rules. In comparison, the federal and provincial governments and some cities place limits on who can donate and how much they can give, how much candidates can spend and what happens to surplus funds. A few jurisdictions have even enacted public funding programs, such as the provincial and federal contribution tax credits, to try and encourage a broader and more representative contributor base. Clearly the rules governing Halifax’s elections could be tighter, but is change necessary or desirable and, if so, what form should it take? To explore this question, Spacing Atlantic has launched a three part series to examine campaign finance in Halifax. The primary question I’m going to explore today in Part 1 is why should we care about campaign contributions at all? Part 2 will take a detailed look at where the money for political campaigns in Halifax comes from and Part 3 will consider what kind of rules we should look at enacting. So without further adieu, here is why should we care.

Corruption

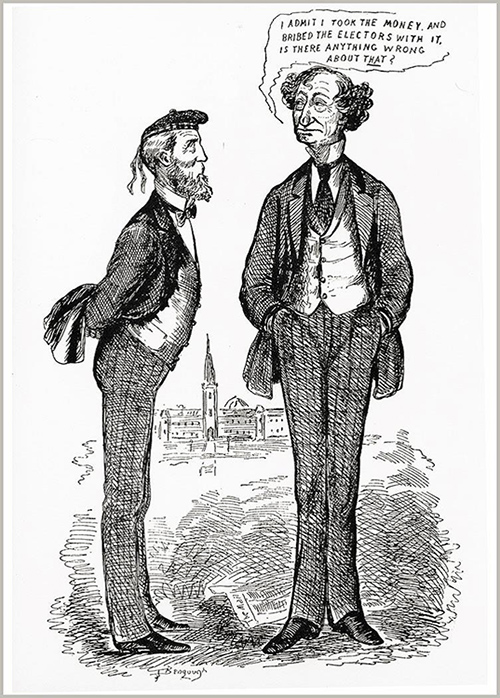

First and foremost, the mix of money and politics can be a toxic brew. There is always the fear that money is donated to secure political outcomes and that donors get “repaid” in the end. Because campaign contributions are an acceptable way to outright give politicians money, they have sometimes been used as a cover for actual bribes. It’s a story with a long history and one that is common throughout the world. Canada’s very first major political scandal involved campaign donations by railroad companies to Sir John A. MacDonald’s Conservative Party. Nova Scotia’s recent MLA expense scandal, although not related to campaign finance, once again reminds us that there are always a small number of politicians who are either in office for the wrong reasons or get seduced by greed once they get there.

Our councillors have generally been a trustworthy bunch. There haven’t been any campaign finance scandals at Halifax City Hall. There have, however, been allegations of shady dealings in the recent past. Former Councillor Dawn Sloane alleged in 2005 that she was offered a bribe by a local developer. Halifax Police investigated, but could not substantiate the claim. During the news coverage of the story, CBC spoke to two former councillors, Len Goucher and Jim Smith, who both said they had also been offered bribes during their time in office. I’m of the opinion that most politicians are in politics for the right reasons. I would be really surprised to learn that corruption was rampant at City Hall. Still, having a transparent and regulated campaign finance regime is a necessary defence to both weed out bad apples and remove temptation. Trust but verify as the old saying goes.

Public Confidence

It’s worth noting that corruption doesn’t actually have to occur for campaign funding to have a negative impact. We live in cynical times and if the public believes that politicians repay big contributors through favourable outcomes, or even just with greater access, than public confidence can be undermined. Simply the possibility or appearance of “buying” an outcome can be as damaging as the actuality. If the belief that contributions help secure favourable outcomes becomes engrained people with a great deal at stake in council decisions might even feel pressured to contribute. To maintain public confidence a transparent and regulated campaign finance regime is required.

Fair, Equitable and Competitive Elections

How campaigns are funded can also have an impact on the makeup of City Hall. If only certain types of candidates are able to raise money, and then those candidates are able to mount more effective campaigns than their opponents, systematic biases can build up over time. In a society with a great deal of disparity between those with the money and those without, wealth can threaten to crowd out other perspectives. In essence, no one needs to actually be bribed because campaign contributors act in their own self-interest to reward their allies, which then makes it easier for those candidates to be successful, skewing outcomes. My past research for my MA thesis indicates that a typical councillor will have significantly more cash available for their re-election campaign than their inaugural race and much of the influx of money for their second campaign comes from developers. Access to contributions is one of the advantages of office and it’s at least partly to blame for the huge advantage enjoyed by incumbents and the general lack of competition in local elections.

An Upward Trend

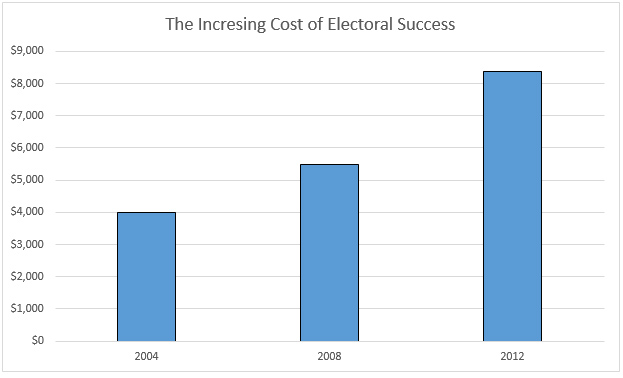

So there is reason to worry about the financing of elections from a perspective of limiting corruption, maintaining public confidence and creating a more vibrant democracy. The question then is should we care about this in Halifax? Is there enough money at play in our municipal elections to make it a real problem? Halifax’s 2012 election is significant not only for the reduction in council size from 23 to 16, but also for the sharp increase in fundraising.

The average amount raised by successful candidates back in 2008 was $5,490, which, when corrected for inflation, was not a significant departure from the approximately $4,000 raised in the 2000 and 2004 elections. In 2012 though, the amount raised shot up to $8,372, a significant 52.5% increase. The increase in contributions in 2012 is likely due to the recent reduction in the number of council seats from 23 to 16. The reduction in seats meant that several incumbents had to run against each other. Having incumbents square off created an unusually large number of competitive races and no doubt put upward pressure on fundraising.

My suspicion, however, is that the increase in fundraising in 2012 also reflects the fact that our councillors now represent more constituents than ever before. More constituents means campaigns are more costly due to the need for more brochures, more mailing, more signs and, potentially, more costly forms of advertising. Our council seats are now larger than our provincial ridings and the days of being able to physically knock on every door in a low-cost grassroots campaign are over. Increasing costs means an increased pressure to fundraise. We’re still a long way from the realities of big cities like Toronto or Calgary where candidates spend tens of thousands of dollars each, but, if 2012 reflects a new normal for Halifax, regulating campaign finance will become increasingly important as we move into a world of more costly professional campaigns.

Checkout Spacing Atlantic tomorrow for Part Two detailing where the money for the 2012 election came from.