HALIFAX – Metro Transit is busy redesigning HRM’s transit network, based on the Moving Forward Principles that were approved by Regional Council in January. The first Moving Forward Principle is to increase the proportion of resources dedicated to high ridership services. The goal is to focus on busier routes. In this column I’ll talk about the factors that drive transit demand, and what that means for where and how service could be deployed in a new transit network. I hope people will join the conversation by posting comments, or by commenting on Twitter with me, @SeanPlans, and @SpacingAtlantic.

Different neighbourhoods have different transit demands. Clearly rural areas with few people have less demand for transit than the inner city. More people equals more potential riders. A crucial point, however, is that per capita transit demand increases with density, which is the concentration of people living or working in a given area. As density increases, the proportion of residents who want to use transit increases. Why?

First, as density increases, you need to provide more service to keep up with demand. Imagine two hypothetical neighbourhoods, identical except for their density. Neighbourhood A has twice the density of Neighbourhood B. In Neigbhourhood B, there is enough demand to fill a bus every thirty minutes. In Neighbourhood A, with twice the density, there is enough demand to fill a bus every fifteen minutes. Fifteen minute service, however, is much more appealing than half hour service. Therefore, a higher proportion of residents in Neighbourhood A would choose to ride the bus, generating even higher demand for transit. Higher densities require better transit service to meet demand, and better transit service encourages more people to use transit.

Second, low density areas are usually places where driving is easy. Parking is often plentiful and free, since there’s more space. Large parking lots and long distances make walking less appealing, and most people walk to transit stops. In high density areas, driving is more difficult: parking is tougher to find and expensive. Transit is often more convenient or cheaper than fighting through traffic or cruising for parking. Additionally, low density areas often have curvy streets and cul-de-sacs, which make it difficult to provide good transit routes. High density areas generally have street grids that favour long, straight, efficient transit routes.

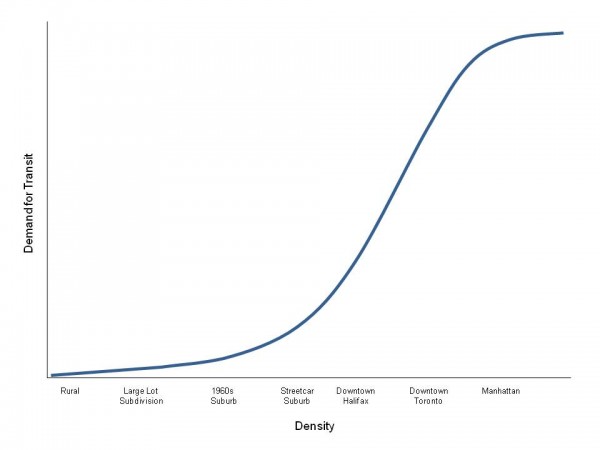

There’s a wide spectrum of urban density. Transit consultant and author Jarrett Walker provides a great overview of the relationship between density and demand in this talk in Toronto. I adapted his graph, below. The demand for transit increases quickly once density reaches a certain threshold. At very high density demand doesn’t grow as quickly. In places like Manhattan, Hong Kong or Paris, the density is so high that many trips are quickly made on foot. Everything is at your doorstep – literally.

Many areas of HRM have good transit demand. Others have very low demand. Regardless of demand, the cost to run a small vehicle is similar to the cost to run a large vehicle. Driver costs – wages and benefits – can make up 70% or more of the cost of transit service. A route with high ridership brings in more revenue from fares than a route with low ridership. High ridership routes require less subsidy from HRM (hardly any transit agencies or transit routes cover their expenses through fares). Focusing on high ridership routes is also the best way to attract the most new riders to transit. High ridership routes can justify more frequent service and more service hours, making transit more convenient and more attractive to a larger portion of travelers.

Many areas of HRM have good transit demand. Others have very low demand. Regardless of demand, the cost to run a small vehicle is similar to the cost to run a large vehicle. Driver costs – wages and benefits – can make up 70% or more of the cost of transit service. A route with high ridership brings in more revenue from fares than a route with low ridership. High ridership routes require less subsidy from HRM (hardly any transit agencies or transit routes cover their expenses through fares). Focusing on high ridership routes is also the best way to attract the most new riders to transit. High ridership routes can justify more frequent service and more service hours, making transit more convenient and more attractive to a larger portion of travelers.

The layout and details of a new transit network in Halifax won’t be made public until the fall, when Metro Transit unveils a draft network. Until then, we can only speculate on where and how service will be deployed. HRM has indicated removing service is a political decision that will be made by Council, not Metro Transit; however, a commitment to higher ridership routes has already been made. I think that Metro Transit will likely stay away from removing service from too many areas. What they will likely do is shorten routes, consolidate routes and lower frequencies where transit demand is lacking. This will allow them to shift resources to higher quality routes with more frequency and reliability. How this unfolds remains to be seen, but there will likely be some heated political debates about what kind of service goes where.

Focusing on busy, high ridership routes will help attract new riders and lower the subsidy that Metro Transit receives from HRM. But what about those people who already rely on transit to travel? Will shifting towards busy routes leave some riders without acceptable service? Next column: balancing the social benefits of transit with other transit priorities.

Sean Gillis is a professional urban planner and amateur transit nerd. He is a member of the grassroots advocacy group ‘It’s More than Buses.’

Photo by Wilson Hum