Touring Edmonton with an outsider is the easiest way to get a handle on the authentic architectural identity that the city displays, beyond pointy pyramidal institutions and a swoopy art gallery. Just try explaining how it is the North and West Glenora are great neighbourhoods while hurling through traffic along 107 Avenue with its 7-lanes of asphalt and tokenistic sidewalks.

Communities throughout the city tend to be architecturally redundant, save for differentiating factors created by vast roadways and the building fashions of the day: large tracts of single detached housing with a small collection of apartments adjacent to a vehicle-oriented shopping plaza, all within walking distance to a public school.

This formula was repeated in the more than 40 inner-ring suburbs that sprang up around the rectilinear city core through the 1950s. Gone was the reliance on grid-like residential areas and axial commercial avenues to connect people to the places they work, shop and play.

This deliberate move was brought to Edmonton by the late Noel Dant: a respected English planner with an impressive academic and professional resume. In 1949 Dant was named the first Head of the City of Edmonton Planning Department, ushering in a fresh approach to the large planning problems of the day: lack of housing stock, a tremendous increase in vehicle traffic, and vast amounts of municipally-owned surplus lands requiring subdivision.

The new enthusiasm for town planning afforded a near carte blanche approach to neighbourhood development. As outlined by Troy Smith’s article Edmonton’s Suburban Explosion, the formula employed by Dant sought to create ideal communities through following considerations:

- Enough density to support a school at the centre of the community.

- Clear boundaries that provide the neighborhood with an identity and legibility.

- The heart of the neighborhood made-up of community oriented facilities, such as schools, parks that residents may walk to.

- Public green space for recreation and attractiveness.

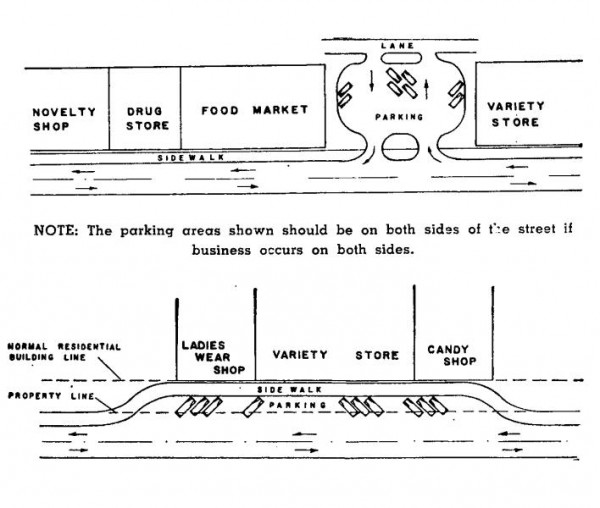

- Convenient shopping facilities should be provided but not necessarily at the centre of the community in order to discourage outside automobile traffic from entering the community.

- The curvilinear street pattern enables the local traffic to be directed in and out of the neighborhood efficiently while discouraging outside traffic from short cutting through.

Dant’s approach worked very well in terms of its ability to satiate the pressing concerns of civic leaders while establishing great communities to live in. Edmonton’s post-war neighbourhoods have long been considered desirable places to live, with proximity to public schools, park space, and easy access to transportation driving their demand. The formula set a precedent that was emulated throughout the city given the tremendous success achieved in accommodating the booming population.

In spite of today’s sustained demand for mature areas, it must be considered that Edmonton’s evolving planning problems are no longer fully addressed by the design of mid-century neighbourhoods. While the basic tenets of Dant’s formula remain valid, these communities appealed to both the needs and wants of citizens at the time they were conceived. Lifestyle was and will always be a large factor in the attractiveness of one community over another, and these municipally planned areas were well suited to the tastes of the day. This is reflected in everything from the wide residential lots, vast strip mall parking, and what are now considered kitschy and fading community shops and services (I think of Pa Peterson’s Ice Cream in Jasper Place).

With all of the rigor that was poured into the comprehensive neighbourhood plans of the 1950s, it seems likely that the outcomes achieved would represent what a planner of today might term sustainable. While density as a key factor in the placement of schools, place legibility, and directed traffic flow are underpinnings of any well-planned community, societal changes are difficult to anticipate and warrant a reexamining of the values upon which these areas were crafted. In short, neighbourhoods designed to Dant’s specifications boast good bones, but are in need of retrofitting to entice the sorts of new investment that drives demand for the schools, recreation centres and shopping plazas that have been in place for decades.

These areas deserve to be revisited with the same sensitivity to civic planning dilemmas and the needs of citizens in the same way. While limitations exist with regards to the placement of infrastructure and land use entitlements, it is possible to effectively alter key underpinnings of these areas, such as density.

Recent bylaw amendments have made way for the possibility of doubling the number of housing on select residential lots in mature areas, though these changes are greatly limited in their applicability to Dant’s communities. By design, Edmonton’s inner ring suburbs are comprised almost entirely of Single Detached Residential Zones (RF1), which is the City’s lowest-density zoning district and not subject to the new provision for the subdivision of 50-foot parcels of land into 25-foot lots. In spite of the limitation, the amendment underscores the fact that neighbourhood densities can be effectively intensified through progressive bylaw change.

Reinvestment has commenced in neighbourhoods across the city, with projects like Glenora Skyline or the Strathearn Heights Redevelopment. Such developer-led projects demonstrate an acute interest in growing the intensity of uses within mature suburbs. Unfortunately, these visions tend to run up against the planning regulations laid decades before. The result is the application of Direct Control Provisions, effectively writing new regulations for every development that is not viable if bound by standard zones.

This approach of planning through exemptions to accommodate growth runs in direct opposition to the philosophy informing the planners who crafted Edmonton’s suburban communities. This begs the question as to whether the regulations laid so long ago should be amended, written around with new regulations, or revisited in a holistic way. While one can only speculate as to what Dant himself would think of the present state of the City, the graceful way in which these neighbourhoods have grown, aged and fostered community stand testament to the power of well-considered comprehensive planning.