Jasper Avenue, Whyte Avenue, 124th Street, Alberta Avenue, 95th Street, 97th Street, 109th Street. What do all of these streets share in common?

The quick answer is their likely inclusion in most Edmontonian’s top list of favourite streets or avenues to eat, shop, wine, dine, and take in arts, culture, and festivities. They arguably contain the most diverse range of the city’s small independent businesses: small ethnic and specialty grocers, high-brow coffee and low-brow diners, bakeries, bistros, theatres, cultural associations, neighbourhood pubs and bars, community services, festivals and markets. They host and express established and emerging cultural and sub-cultural identities of our neighbourhoods: take Chinatown or Little Italy, or the resurgent energy and diversity of Alberta Avenue, as examples. They are streets and avenues where young entrepreneurs and new Canadians perceive a community demand or desire and try to fill it while making a living.

These streets and avenues do indeed share a meandering list of good things in common, but a historic thread of urban history weaves these and other interesting streets and avenues of Edmonton together:

They are all former streetcar routes.

Although harder to fathom when wedged between massive trucks aggressively tailgaiting down the Henday, Edmonton like most Canadian cities, was first and foremost a streetcar city.

There is a renewed academic interest in the role the streetcar played in the urban form of today’s cities. In Vancouver, it is widely acknowledged that its most popular public walking streets coincide with historic streetcar routes. Despite the many decades since the streetcar last operated, it is credited with giving Vancouver its ‘good bones’. Patrick Condon, Chair of Urban Design and Landscape Architect at the University of British Columbia, author of Seven Rules for Sustainable Communities, is an outspoken planning advocate for “the streetcar city”. Condon notes:

“the streetcar established the form of most U.S. and Canadian cities. That pattern still constitutes the very bones of our cities — even now, when most of the streetcars are gone. […] Virtually all of the city of Vancouver’s richest social settings are on streetcar arterials. While the high-rise neighborhoods of Vancouver are justifiably famous, almost all of the rich street life of the downtown core still occurs on the streetcar arterials of Granville, Robson, Denman, and Davey Streets. Beyond the core lie miles and miles of very active streetcar arterials. These streets are typically thronged with pedestrians, in numbers that rival the much higher density areas of New York City. “

I spent ten years in Vancouver’s West End walking mainly its former streetcar arterials without the connection. As a returnee less informed about the history of my hometown, I was curious to know if the same urban paradigm applied to Edmonton: what is the extent of Edmonton’s historic streetcar system, and does it share the same relationship to urban vibrancy today?

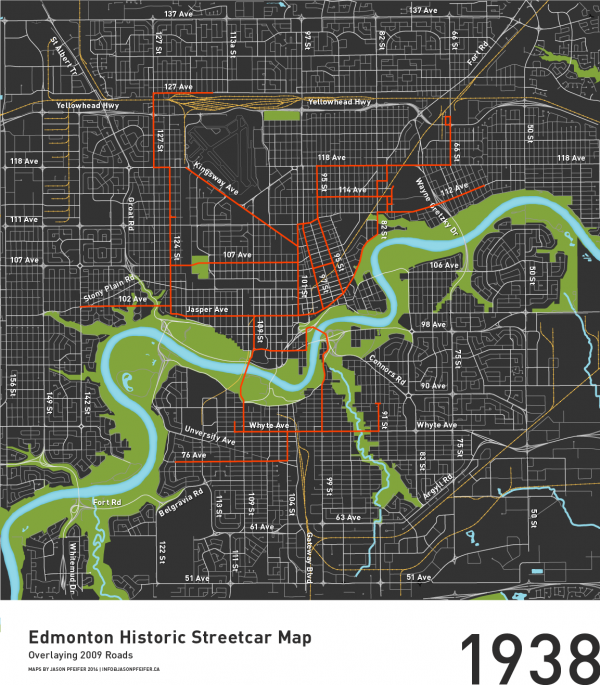

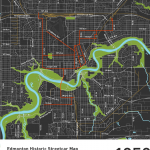

Leaning heavily on Edmonton’s Electric Transit, The Story of Edmonton’s Streetcars and Trolley Buses from our fabulous EPL, I recreated digital versions of Edmonton’s streetcar system (by the specific years published in the book), and overlaid them on the contemporary road and rail network. Published first today on Spacing Edmonton; the results are intriguing:

The streetcar of yesteryear served a list of neighbourhoods considered favourites today: Oliver, Glenora, Strathcona, Westmount, Belgravia, Highlands, Alberta Avenue, Bonnie Doon, Garneau, Belgravia, and more. So what is it about the streetcar as a method of mobility, that influenced the urban form of the city? In Seven Rules Condon has a great parable describing “a day in the life” in the early streetcar age of Vancouver, which is a recommended read but let me summarize:

- Pre-dating the age of widespread automobile ownership, developers owned land at too great a distance for people to travel on foot from jobs in the central area.

- In order to make the land saleable, developers built, owned, and operated streetcar lines that dramatically decreased travel time.

- The citizen’s next expectation after getting to the new neighbourhood was proximity to essentials like food and clothing. Developers wisely lined streetcar arterials with a variety of commercial shops.

- In order to prevent financial losses on operating the streetcar, houses had to be built at densities high enough along major streets to have enough fare-paying riders (at least 8 houses per acre).

- A five-minute walk from a home to a streetcar (and shops) became a formula that worked well for the commuter, and hence developer.

The resulting quality that, according to Condon, is somewhat unique to North American cities is a set of interconnected public spaces that are linear in form. This is contrasted with the more traditional planning focus on activating ‘nodes’ or destinations, and less emphasis on the linear spaces which connect them.

It would be remiss not to acknowledge the negative perceptions that some of these streets have or have had in the past. I am admittedly old enough to recall some of these streets as the city’s ‘seediest’ areas. This isn’t to suggest that the streetcar street is some form of urban panacea, but rather that as public spaces they are a prominent expression of a neighbourhood – whether its illness or health.

Interesting prologue: The streetcar for a very brief period in 1913 extended all the way down Perron street in St. Albert before catching fire in 1914. If plans come together, St. Albert might see rail return 30-40 years from now.

Works Cited:

Condon, Patrick. “2.” Seven Rules for Sustainable Communities.

Hatcher, Colin K., and Tom Schwarzkopf. Edmonton’s electric transit: The story of Edmonton’s streetcars and trolley buses. Toronto, Canada: Railfare Enterprises Ltd., 1983.

Jason Pfeifer is an Edmonton based Landscape Architect and Urban Designer, and Principal of PD+A Studio, a boutique service-oriented interdisciplinary design firm.

7 comments

Great exploration piece and wonderful to see the mapping – I do think there is a a correction to be made to the line on 114 Ave, a nudge one block north would place it correctly – it ran along 115 Ave just as the Route #3 bus does today, and the remains of the old streetcar building infrastructure can still be found at the east end of 115 ave and the present day LRT tracks. http://www.edmonton-radial-railway.ab.ca/_documents/StreetcarRoutes.pdf

There seems to be some conflicting information out there! Hopefully we’ll resolve this soon.

The resources we were able to find indicated it was down 114 (Spruce) Avenue: http://www.tundria.com/trams/CAN/Edmonton-1945.png

Also see 1917 on the timeline here: http://www.edmonton-radial-railway.ab.ca/streetcarhistory/streetcarsystem/

Hi Colin,

Hmmm, yes double-checked my sources as well, and have 114th.

However, very interesting as I did mention that 114th curiously is one of the few that seems odd to have been a streetcar street given its character today and lack of indicators. Definitely possible it is incorrect.

between 116th ave and 117th ave there were cromdale offices and cromdale car houses and shops. Between 115th and 116th looks like there was a power substation, which as far as I know from Google Earth still exists, is that it? And at the north end of the oval track there there’s a car turnaround that ran down 78st. until it met up with Jasper. Edit: the buildings I am referring to are on 80th street.

Thanks for raising this. 114th ave has always seemed like an oddball since I’ve started looking into this, especially since it ran there for a good period of time as well.

I’ve got Ken Tingley’s “Ride of the Century” here in front of me. On p. 88 he reproduces a 1924 map credited to ETS and it clearly shows double tracks on 114 Ave. between 89th and 79th. 114 today looks too narrow to have had even one track on it. I wonder if the two tracks ran where the trees are now, sort of like the way they used to run down the middle of Whyte were trees are today.

But 115th now sure does look more like a streetcar artery.

An interesting additional note is that the line along 76 ave was a recreational service bringing people to (now drained) McKernan Lake for swimming in summer and skating in winter.

Jason, I echo Colton. You’ve done excellent work updating the Hatcher & Schwarzkopf maps and introducing the old streetcar routes to a new generation. One thing that struck me when I saw them was that Norwood Boulevard didn’t have a line east of 95 Street. It makes sense given the narrowness of this segment of road but also seems incongruous given the great urban fabric between 92 and 95 Streets. For the last number of years Councillor Caterina has been working to get people to pay attention to Norwood Boulevard. Your maps helped me realize that its lack of investment started much earlier than I had supposed.

Hi Erik,

thanks for the comments. I’m maybe a little confused because to my knowledge Norwood Boulevard is essentially 111th avenue until it migrates north to 112th, and, the east-west Norwood line does terminate its eastern direction at 95th on my maps, where there’s a line that goes north to 118th avenue along 95th street. Am I perhaps misinterpreting something? Looking at it now though, it’s clear that 111th should be labeled. Is it officially renamed to Norwood Boulevard now or is it 111th?

Regardless, I’ve just emailed The Edmonton Radial Rail Society seeking the discovery of an authority on the matter, who will scrutinize and resolve discrepancies in the data sources.

I will correct anything inconsistent in the images and point out the edits made at the end of this article.

In the near future, I plan on creating another version of the map showing the extents of the line when it went out to St. Albert for a brief 6 months. There are still traces of the St. Albert line in property lines and perhaps even the landscape, something which I plan on exploring more after the melt.

Erik, interesting observation! Though I question whether or not Norwood Boulevard had the commercial support we’d expect along streetcar lines. I would like to believe that the proximity to the streetcar still could provide enough support for businesses. Stony Plain Road in Jasper Place immediately comes to mind.