Let me clear the air before I go any further: I don’t personally believe physical places (such as cities and regions) have become irrelevant. In fact, I believe that “being-in-the-world” is a fundamental part of being human and that our experience of physical place is primordial – that is to say, it always comes before our experience of imaginary, digital and other non-physical places. On a more pragmatic level, a great number of human beings live in places that are physically unsafe for one reason or another, and most of them cannot escape the physical reality in which they live (according to a 2005 UN report, more than 1 billion people live in slums worldwide). Hence, talk of the disappearance of physical place is mostly Silicon Valley rubbish, in my opinion.

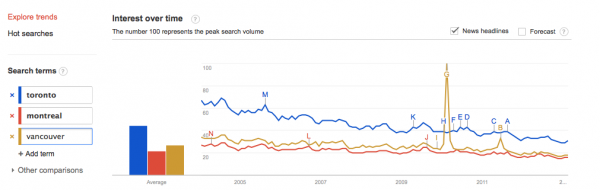

Except that one must reckon with certain troubling facts and empirical trends that raise serious questions about the place that places occupy in our lives. This trend, which I discovered (as many others before me I’m sure) while using Google Trends to collect data for my Ph.D. research, is staggeringly simple: the number of Google searches for several important physical places has decreased dramatically since January 2004 (the starting date of GoogleTrends); for example, out of the 110 largest metro regions in North America, 19 only were searched more often in December 2012 than they were in January 2004. This is in spite of the fact that the number of internet users has more than tripled over the same period while the number of tourists in a given year worldwide has increased by at least 200 million (from 755,000,000 in 2004 to 940,000,000 in 2010).

These trends are, in my opinion, troubling in and of themselves, but they are especially so considering recent findings that trends in Google searches correlate closely with real-world phenomena, such as the progression flu. In my own research, I use Google to look at the variation in something I call “regional awareness”, measured as the number of searches of a city’s name followed by “region” as well as preceded by “greater” (e.g., “Montreal Region” and “Greater Montreal”). Interestingly (but also weirdly), I found several statistically significant relationships between the number of Google searches for these two expressions and a number of regional variables (such the number of municipal governments per 100 000 people in a given region, the diffusion of spending power within a region or the growth rate of a region’s economy) even when controlling for population, median household income, educational attainment and several other socioeconomic and political variables. Of course, I cannot be sure that I am measuring what I think I am measuring (i.e., regional awareness), but one thing is certain: I am not merely measuring noise.

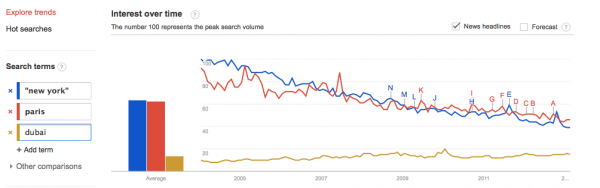

Similarly, when it comes to the decline in the number of searches for cities as varied as Toronto, Montreal, Paris, London and New York, one cannot “affirm” that it is due to the growing irrelevance of physical place. But I have to admit, none of the other hypotheses I can think of stand the test of evidence:

The Baidu hypothesis: One might think that the number of Google searches for physical places is due to the rise of other search engines, like Baidu in China. While it is true that Baidu now captures nearly 80% of all searches in China and that it is still growing, Google’s global market share has increased significantly between 2004 and now (from 56.5% in 2004 to about 83.46% now). Hence, the decline in the number of searches for cities and other physical places cannot be attributed to a general decline in the number searches.

The Dubai hypothesis: A relatively simple and sensible explanation for these trends might be that other cities are taking the place of London, New York and Paris in the “collective unconscious”. But intriguingly, the number of searches for cities like Dubai, Shanghai and Mumbai has actually not increased steadily – and certainly steadily enough to account for the sharp decline in the popularity of Paris and New York (see below) – which, by the way, remain quite a bit more popular than the aforementioned “new global cities”.

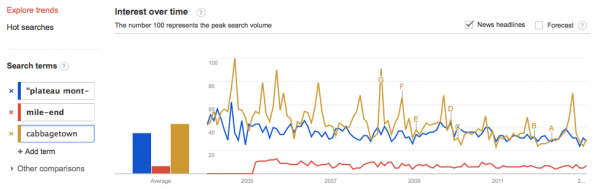

The glocalization hypothesis: One might argue that it’s simply a question of scale: the world is going glocal, and large cities might just be losing their groove, while “local” places are becoming more popular. If the trend below is any indication, however, that hypothesis also seems flawed. Indeed, the Plateau, the Mile-End and Cabbagetown (in Toronto) all seem to be slowly losing popularity.

The Smart Phone hypothesis: The last hypothesis that I seriously considered is the possibility that Google searches for physical places may be declining as a result of people’s use of smart phones to look for “place-related” information. But considering that the iPhone was only launched in 2007 and that the downward trend in searches has been going steady since 2004, it seems obvious that there is more to it than that. Sure, a billion smart phone users might make a dent in the number of Google searches. But my guess is that most of those smart phone users are also higher-than-average internet users…

I don’t have an answer for why this trend is showing up, but as I can’t think of a solid hypothesis to “explain it away”, I am stuck with the question that I start with: are physical places losing relevance – or perhaps just popularity?

If you have an alternative explanation to propose, by all means share it. I’d sure love to know.

Post-script: It is important to note that a vigorous (academic) debate about the physicality of place and the role of technology in mediating our relationship to the world has taken place in the 1990s, at the onset of the digital revolution. Nicholas Negroponte, among others, predicted, in 1995, that “digital living [would] include less and less dependence upon being in a specific place at a specific time” (p.165). In the phenomenological camp, a large number of scholars vehemently denounced what they saw as the imposition of a particular, technologised way of studying the world. Robert Rundstrom was particularly vehement when critiquing academic geographers’ newfound fascination for Geographic Information Technology: “[digital] geographical ‘re-presentations’ […] and other exotica are just a part of a much larger world of inscriptions used in Western technoscience to disenfranchise indigenous peoples” (p.51). However, there is one important difference between that debate and the contemporary discussion of the same issue: theirs was a largely theoretical exercise, whereas the contemporary discussion is based on solid, hard data. Therefore, while it is important to acknowledge that the debate has already been had, it is also important to reckon with the new available facts.

4 comments

Are we sure this has to do with cities? Terms like “Canada” and “China” are also declining in Google Trends. I’m not sure long-term trends in Google Trends are really meaningful in absolute terms, couldn’t they be due to changes in Google’s algorithm or choice of content to index?

Are Google Maps searches included in Google Trends? It seems to me that they are not, so the steady rise of Google Maps since 2004 could play a part in decreased Google searches for places.

I think one should be really careful in interpreting the data. It seems that the google trends graphs, as displayed, actually represent some normalized data. And for any point, they don’t represent absolute number of search queries: “This analysis indicates the likelihood of a random user to search for a particular search term from a certain location at a certain time.”

So it’s possible that terms are slightly declining over time – as your analysis shows – not as a result of fewer number of absolute searches, but people using google to search more for other terms. I am not sure whether this should be interpreted as a declining interest in the steady terms, or merely a change in the behavior related to how we utilize the internet. For example, the internet/search culture may have changed to tend to follow trending subjects much more. Or more searches nowadays may be by people being too lazy to put in the full names of web-addresses, resulting in more relative queries for website names minus the .com.

I would propose a set of control tests, if you will, to see whether declining search volume for a term relates to less interest. I have a feeling that searches for simple real-world terms like cities is declining in general. So I tried words like “bicycle”, “car”, “hammer”, but also “Canada”. They all seem to be slightly declining over time. For bicycle (in Canada) in particular that seems strange, because I know that the amount of cycling has increased over the years.

Another issue is making global graphs. Your first graph shows Montreal, Toronto, Vancouver, as “worldwide” searches, since 2004. Now if you change the graph to show search from Canada only, the decline over time is much less pronounced. And again this makes sense: most searches for those Canadian cities comes from Canada. But if you consider that in 2004, a larger percentage of the world population with access to intenet was Canadian compared to today, than the same number of Canadian google users searching for Canadian cities will result in fewer relative searches for those cities globally.

So If I take these ideas into account, and I search for a couple of US cities, only counting American users, and search Los Angeles, New York, Seattle, Chicago, Boston, I see them all declining by similar amounts as the previous tests, about 15-30%. It’s only New York that declined by more than 50%. So Yeah, interest for searching New York on Google appears to have declined.

It seems to me that it’s mainly due to the way Google has built its algorithm. Google “learns” your location over time, meaning one user doesn’t “need” to type its location over time. Unless you specify, Google assumes you’re in the same place/city as before.

So I ‘d think people are slowly (unconsciously?) learning that, so they don’t type their location as much.

My two-cents…