A Community Planning Board (CPB) can be an effective democratic platform to support meaningful citizen engagement and push forth social justice and equity in planning. While neighbourhood associations or residents associations may address similar issues, a community planning board or advisory group can focus on the intersection of top-down planning and neighbourhood planning. CPBs need to address the growing concern about resident participation in the planning process, and advocate for significant improvements to reactionary and unequal public participation processes. These boards can serve to engage residents on planning issues and to help communities identify contentious issues in order to better communicate them to their elected officials. Incrementally, they can begin to influence larger policy and structures by evaluating limitations to participatory practices, beginning the process to reclaim participatory processes in Toronto. Even though planning boards have no official or legal power, they can still be effective by leveraging their political and social power to represent a collective voice, rooted in social justice.

Participation on a planning board can help foster inclusion among community members, function as an educative tool, strengthen democracy, support local leadership, increase civic awareness/knowledge, and increase government and organizational accountability. The very ability to participate in local affairs can increase feelings of empowerment and self-confidence. However, a community planning board can face legislative, political, structural and administrative limitations. For example, CPBs can easily be co-opted by political or externally imposed objectives. In New York City, boards have been criticized as being an arms-length organization of the City, seeking approval for developments that fall in line with a councillor’s agenda, as opposed to maintaining their own community vision. Without clear expectations, or an agenda rooted in social equity and justice, planning boards can exercise exclusion and corruption, meeting the desires of the status quo while further distancing marginalized populations.

Despite potential limitations, CPBs can be effective platforms to increase urban literacy, allow for a shift in power, and set forth a neighbourhood vision. Planning boards can help to decentralize decision making processes. They break up and diffuse power, while providing a platform for community residents to discuss the physical and social development of their community. The power that CPBs can leverage does not come from any legal structure or powers, but from their political and social influence. Planning boards often gain power and a ‘voice’ due to development pressures and real estate market changes happening in their community. The capacity to participate and have influence or power only becomes a reality with development pressures, allowing the CPB to potentially negotiate changes to its neighbourhood.

The Centre for City Ecology and Social Planning Toronto have been working in the Kingston Galloway/Orton Park (KGO) community, alongside community members, to explore the formation of a community planning board for the neighbourhood. The proposal received the support of local Ward 43 Councillor Paul Ainslie, to recognize the implementation of a pilot project in KGO. The goal of the CPB is to begin discussions and visions for their community in advance of development pressures, with the intention to address growing concern about resident engagement in the planning process, advocating for significant improvements to reactionary and unequal public participation processes. In Toronto, there is no legal requirement for the city, private or community groups to consult and/or work with planning boards. This places a board at an interesting crossroad. On the one hand, a planning board could politicize and reclaim participatory practices and community planning. On the other hand, the board could become a depoliticized, market-driven entity, supporting the status-quo. The former is definitely a struggle to achieve but it can lead to greater social transformation, not only for the residents and members involved in the process, but potentially for community planning and participatory practices at large. The latter could lead to a community planning board that perpetuates existing power struggles, further marginalizes community members, and provides minimal short-term benefits for its residents. Board members need to keep in mind that they are a community-based organisation and not an extension of the City, allowing themselves to really explore and identify progressive ways to address neighbourhood planning issues.

There is greater potential for active community boards if they are located in Toronto’s downtown neighbourhoods, where there is a higher exchange value for land (such as social housing blocks that have become ‘hotspots’ for mixed-use development like Regent Park, or communities facing transportation-infrastructure developments such as along Eglington Ave.). Particularly in Kingston Galloway, a CPB’s power becomes evident when there is interest in their community by someone else, meaning that power will come with development and ultimately gentrification. Only once there are development pressures can the CPB exercise its power to try to influence the future of the community, and to mitigate some of the negative effects of development. The proposed community planning board in Kingston Galloway/Orton Park is in the best position to begin this process, prior to increasing developmental pressures in the area. The board has the opportunity to set the ground work for neighbourhood planning through the creation of a strong vision and operating structure that can help mitigate the negative impacts of gentrification.

As development pressures begin to rise in the community, the board has the opportunity to organize resistance to gentrification before it changes the composition of the neighbourhood, and sooner or later, the board itself. Creating a board with a strong mandate rooted in social justice will ideally help mitigate future social power dynamics as the neighbourhood gentrifies. A long term mandate that places residents at the forefront and seeks to use development as a means for social transformation can lead to a very powerful community planning board. For a planning board to be successful, it must reclaim the politics in participatory planning, moving beyond itself to seek long-term social justice for its residents. This is, of course, not a simple endeavour. They must begin to set their agenda and invite the government to respond. Community members must start to think of themselves as the subject of policy and not the object of it.

Mojan Jianfar, is a passionate city builder, with an interest in systems design and innovative practices. She is a facilitator and workshop designer, focusing on innovative and creative ways to engage participants in urban affairs. She is the Director of Projects and Partnerships with The STEPS Initiative and a member of the Professional Advisory Committee piloting a Community Planning Board in Kingston Galloway/Orton Park, which was also the basis of her MES masters research paper. Find her on Twitter @mojanj or email at mojanj@gmail.com.

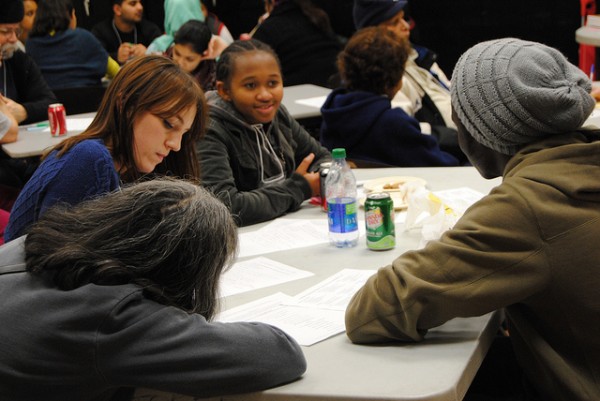

Photos courtesy of the Centre for City Ecology

2 comments

Be careful of the NIMBYs. Not in my backyard?

You want a place to live? Good that gives me a chance to extort you. Why? Because I can.