We currently dedicate an excessive amount of street public space for the movement and storage of automobiles. We can bring dignity to our streets where people live, work and play by reclaiming it for people. It has been shown that cities are significantly quieter when there are lower traffic volumes, or even when the vehicle traveling speeds slow down to a more humane speed (40-30kph). There are also fewer automobile related injuries and fatalities. It can also make us happier since we can spend more time outside and meet more of our neighbours.

So how can we reclaim some of this space? Pedestrian streets offer one way to do this, but it has been demonstrated that pedestrian streets in North America have failed in the past (see Buffalo’s Main Street, Ottawa’s Sparks Street, and other examples). Interestingly, many European cities of different sizes, climates and cultures feature widely-visited, vibrant pedestrian streets. These include Northbrook St. in Newbury, UK (pop. 31,331 in 2011), Calle San Jacinto in Seville, Spain (pop. 702,355 in 2012), Exhibition Road in London, UK (pop. 8.3 million in 2013). They also exist in various sizes either as a short section of one street or a network of car-free streets like those in Delft, Netherlands or the Stroget in Copenhagen. This article explores several of these successful pedestrian streets and breaks down several of the elements that make them work.

Single Street Pedestrian Zone

Northbrook St. is a pedestrian street in Newbury U.K that was established in 1998. The zone is only closed to automobile traffic from 10 am to 5 pm using electronic bollards. The absence of cars also allows markets to regularly set up two-three times a week.

After 15 years, the results are dramatic. Northbrook St. is a bustling and vibrant street full of people. The street is lined with outward facing fine-grained retail uses, which is critical for attracting people and ensuring its success. People are attracted to visual stimuli, therefore, having many small building fronts and many stores displaying their wares in the window present a wealth of details that will attract people’s attention inviting them to stay and linger (similar to the photo above). Fine-grained retail uses means that building facades are varied and interesting enough that our sensory experience is enhanced. Also critical for pedestrian streets is to have public or private places to sit. This can include formal seating—such as benches, movable tables and chairs—or informal seating, such as the steps of a stair, planters, or edges.

Shared Streets

Successful pedestrian streets do not mean you have to close the street to vehicular traffic completely. The Exhibition Road in London was an attempt to create a different kind of pedestrian street and is an example of a ‘naked street’—or a shared street—where access for all modes is provided, but the most vulnerable modes (walking and cycling) are prioritized. One of the more well known examples of a naked street is the Poynton intersection. All of the traffic signs and road markings are removed while street use and safety is regulated by the unpredictability factor of a street with no traffic control mechanisms telling you how to behave. Consequently, drivers are more cautious and alert as they navigate the street.

Exhibition Road can only be called a partial success as it is only on the south portion where people are present. What is the reason? Well, this is the only segment of the street that is lined by fine-grained ground floor retail and skinny building facades. The remainder of Exhibition Road is flanked by large museums and limited street facing retail uses that do not actively engage the street.

Wide open spaces with clear lines of sight permit people to feel like they can get away with driving through quickly. In order for a shared street to work properly, it needs to have edges that create friction to force drivers to slow down to human speeds. These can either be hard edges through the use of landscaping or design, or soft edges like having people present. Ensuring that you have fine-grained retail with many store fronts lining your pedestrian street will ensure there are plenty of people. These uses also invite people to stay and partake in many activities including people watching, shopping or eating.

Car-Free Centres

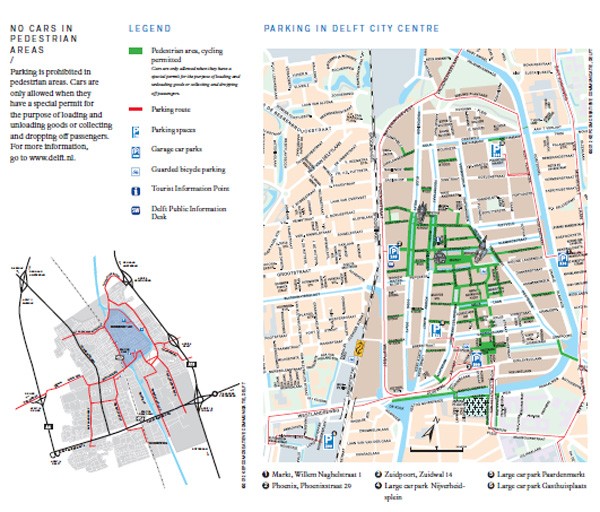

With a population of about 100,000 people, Delft is a relatively small Dutch city with a network of car free streets in the city centre. Like any other city in the 70’s, its city centre public spaces were dedicated as car-parks. Today, the city centre could be referred to as a place of “people-parks”. The lack of automobiles has a dramatic effect on the experience of the city, most noticeable is the quietness.

Delft took a slightly different approach to create their car-free status. The city built a series of parkades around the perimeter of the city centre. They also invested in digital wayfinding signage, directing people to the nearest parking garage and indicating the real-time capacity of available parking stalls. The wayfinding also indicates the walking distance from the parking garage to the city centre. Consequently, on-street parking is priced higher than the parking garages. Finally, the entire core is within 800 meters—or a 10 minute walk—from a local tram service and regional train station.

All of this encourages people to spend less time circling for parking and more time shopping within the core. While driving in the core is discouraged, people are still allowed to drive into there during the evening hours for critical deliveries and pick-ups, with the appropriate permit. Since the core is also more comfortable for walking and cycling, it provides significantly more capacity for people, while still maintaining walking distance access for those that need to drive.

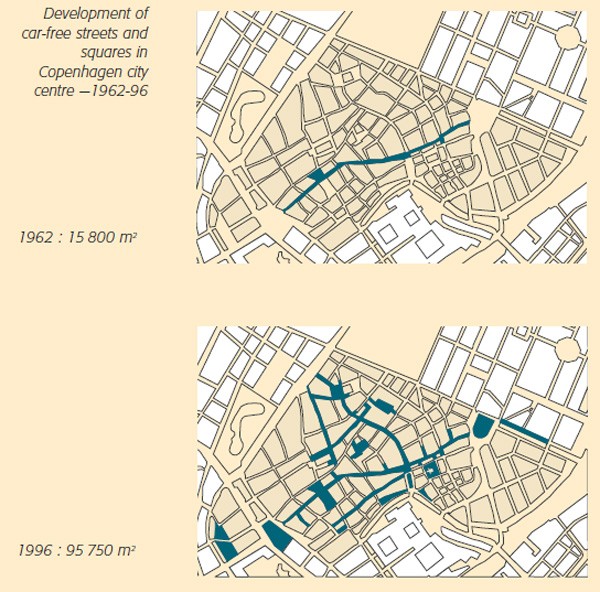

Pedestrian cores can also work at a larger city scale such as the Stroget in Copenhagen (pop. 569,557 in 2014). Starting as a temporary trial and created in 1962, the idea faced intense opposition from the adjacent merchants who thought it would kill their businesses. Over time, the Stroget expanded to include more streets and plazas, and grew to currently cover over 1.8 km of streets today. It is a great success with numerous new cafes, shoppers and street life. In the summer, the Stroget sees an average 80,000 (2008) people per day passing through its pedestrian network. In the winter, there is on average 48,000 (2008) people.

From these examples, it is clear there is no single way to create a pedestrian street. However, there are several key ingredients. It is important to create a comfortable, human-scaled environment that provides access for all modes but maintains a pedestrian speed. Access for automobiles can be provided either during off-hours or evening, or be tolerated in low volumes travelling at human speeds using designs that force drivers to “feel unsafe travelling at unsafe speeds.”

It is also important to have streets lined with fine-grained, street-facing retail uses with many store fronts that offer a wealth of activities and details. This is important for creating an interesting place where people want to stay and also speaks to the important of retail frontage dimensions when designing adjacent architecture.

It may also be important to take an incremental approach and starting small at first—i.e. only opening the street to people walking and cycling during day light hours, or only creating a small pedestrian street segment. It is better to create a small, high-quality pedestrian-only street than a large ambitious pedestrian-only street that doesn’t work. The larger the pedestrian street becomes the more issues one has to address, such as storing cars and providing crucial delivery access.

Keeping pedestrian streets smaller initially guarantees that the complexity and costs are lower. Furthermore, the impacts to vehicular traffic flow are likely to be negligible, as there are many alternative routes and there is greater vehicle access to the site. A small but successful pedestrian street is also more likely to seem fuller than a mediocre large pedestrian street…adding to its allure.

Pedestrian streets can also be set up with low costs as a pilot project, using nothing more than a temporary barricade to block or slow down vehicular traffic and create an inviting and comfortable environment. After a pedestrian street has gained success, it can always be expanded on to include more hours or more streets.

***

Slow Streets is a Vancouver-based Urban Design and Planning consisting of Darren Proulx and Samuel Baron that provides original evidence for people-oriented streets. We believe streets serve many uses beyond moving automobiles quickly.