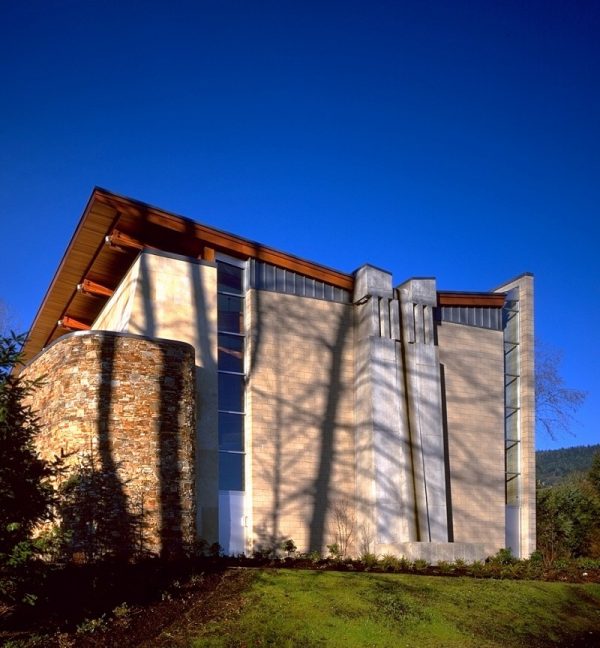

While an architecture student at UBC in 1998, our class was asked to go out around Vancouver and photograph examples of ‘weather registers’, instances in the built environment where nature was overgrowing the architecture. As it happened, my apartment building was undergoing an envelope restoration, an ubiquitous sighting at the time to say the least. Suffice to say, I had a pretty easy assignment. Others took pictures of moss grown roofs and cracked concrete slabs. However, a select few took pictures of a recently built synagogue on the north shore. The architects of the building had designed one façade to be dominated by a massive rainwater sluice which, at that time, was just beginning to water stain the concrete on the synagogue’s east facade.

This poetic piece of architecture, the Har-El Synagogue in West Vancouver, turned out to be the work of Acton Johnson Ostry Architects—a then seven-person, five-year old office which had, by that time, already established itself both locally and nationally, being recipients of several architecture awards from the design community (four alone for the Har-El Synagogue). By combining the skillful siting of the building with immaculate attention to material detail, along with a confidence in their ability to deliver their client’s vision, the firm had, in a short time, developed a tripartite mastery of cultural, tectonic, and, business acumen in architecture.

Fast-forward twenty years and though the firm has changed in terms of its size, location, and name, the song has remained for the most part the same. And with just recently having celebrated the twenty five years since the firm was founded, the office has produced for the occasion a handsome monograph, appropriately featuring twenty-five of their projects. More than just a marketing piece though, the book is a thoughtful product of the firm’s finest achievements in its quarter century, complete with a humourous introduction in which its ad hoc formation is revealed, where the appearance of a busy office was staged, complete with a receptionist, while they were being interviewed by what was to become their first client.

That project would become the Chief Matthews Primary School, and it is the first project featured in the book—a formidable point of departure, as it would prove to be a catalyst for other prominent architects to likewise work with other local Nations to realize new schools and community centres. The remainder of the book is a testament to the firm’s uncanny ability to create both socially and environmentally responsible architecture for numerous building types—schools and community centres, synagogues and churches, restaurants and multi-family high-rises are all featured in their twenty-five year retrospective. And most recently, two projects have challenged the status quo in how we think about the residential high-rise building, both environmentally (Tallwood House) and socially (The Duke).

In the case of Tallwood House, the firm accomplished the feat of realizing what was at the time of completion in 2017, the tallest contemporary wood building in the world, while providing much needed student housing at UBC. As one of the newest additions to the campus’ sustainable building portfolio, Tallwood House was developed as part of the Tall Wood Building Demonstration Initiative launched in 2013 by National Resources Canada and Canadian Wood Council that aimed to demonstrate that mass wood structures are economically viable for high-rises.

As the first building to be realized in the Brock Commons complex, Tallwood House provides accommodation for 404 students, while being a living laboratory for UBC students and faculty. The wood framing is a hybrid of three major products: cross laminated timber (CLT) for the floors, glulams for the columns, and concrete for the first floor podium and cores. And if you had been on campus during the initial construction of the building as I was on one occasion, you would’ve been able to see the two reinforced concrete cores, standing precarious at 18 storeys each, prior to the wood elements being built up around it.

And as other architects are exploring the possibility of building wood tall, Tallwood House stands as a high-water mark, as well as an ethical challenge to the development industry to build more environmentally-minded structures. For as our climate crisis worsens and the general populous continues to become educated on what the underlying causes are, the masses will demand no less from the developers, making it possible for us to overcome the challenges of building tall in wood for a future where we can minimize the embodied energies used in the production and construction of buildings. Though Passive House has picked up on this trend, it has done so only from an energy consumption standpoint. Tallwood goes one step further, providing a solution more bred in the bones of the building itself.

And similarly with The Duke—one of the firm’s most recently realized projects, and the last one featured in the monograph—Acton Ostry Architects continues to push the envelope of what a building can be, this time with a social agenda rather than an environmental one. Realized for Edgar Development Corp, Acton and Ostry worked closely with their client to ensure the project did not get caught up in the City of Vancouver’s current planning miasma, providing a nimble response to concerns brought up by both the neighbouring residents and the planning department. The result is one of the most successful market rental high-rises to be realized in the city to date.

At 14 storeys tall, the building’s most evocative feature is its trapezoidal shaped central atrium, running up the extent of the tower, the open corridor around it acting as a social condenser for the building’s occupants, with a colourful palette of front doors combined with a well-conceived and executed guardrail detail. With the client being a relative newcomer to the local development scene, there was a willingness on their part to allow the architects some leeway in which they could communicate: allowing details that would typically be value-engineered away. And of course, at the end of the day, the proforma for affordability was achieved, despite its postal code being in central Vancouver.

Other highlights of both the monograph and the office’s portfolio include the restoration of the old Salt Building, constructed in the 1930’s in southeast False Creek, located at the centre of a new vibrant community on the site of the former Olympic Village for the 2010 Winter Games. With the microbrewery pub Kraft having made itself right at home, the one hundred taps featured provide for a captive audience who can now partake the decades old heavy timber framing, much of it preserved from the original structure.

AOA have also completed several restaurants for the Cactus Club, including a unique signature building on English Bay, on a much coveted site that many would’ve said could not be built upon. Here again Acton and Ostry were able to demonstrate their ability to overcome the roadblocks of onerous permitting processes and NIMBYism, resulting in one of the chain restaurant’s most popular locales.

Beyond the Tallwood House at Brock Commons, AOA has also been able to realize several other projects for the University of British Columbia, including the campus’ new Aquatic Centre and a new training facility for the Whitecaps and Thunderbird varsity soccer teams. All of these projects—along with the schools, churches, fitness and community centres—all attest to the desire for Acton Ostry Architects to foster social sustainability, one in which buildings can give back and enrich the lives of their occupants.

This social responsibility also extends to the office itself, where they continue to nurture the interns that have come and gone through their doors (and who are all named in the closing pages of the book). It is clear that they understand that by mentoring the next generation of architects, much as they were mentored by the likes of Peter Cardew and Richard Henriquez, they likewise can give back and ensure a future generation of thoughtful architects.

And as both Russell Acton and Mark Ostry look ahead to the next quarter century to see what challenges lay before them, at only twenty five years young they know they can and still have much more to accomplish.

***

Sean Ruthen is a Metro Vancouver-based architect and writer.

One comment

Sean Ruthen continues to produce the most interesting and insightful reviews of architecture and architects.