As the new BC/Yukon regional director of the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada, I recently had the privilege of meeting in June with my fellow board members in Charlottetown, PEI. With the RAIC currently reaching out to members in Atlantic Canada as part of an ongoing membership engagement—one which has now traveled coast to coast, with the intent of discussing the new RAIC chapter and network model in each of the four Atlantic Provinces—the board and myself were invited to be part of these initial conversations. This provided a rare opportunity to look at this small port city with my Metro Vancouver, west-coast eyes.

While there, I serendipitously found myself reading Small Cities, Big Issues, a new collection of social work case studies on the marginalization of people in small, mostly British Columbia cities, where the issues once thought to be exclusive to Metro Vancouver are now showing themselves in Kamloops, Nanaimo, and Prince George, to name only a few examples. As defined in the book’s introduction, a small city’s population is typically somewhere between 10 and 100 thousand people, and at just 36,000 souls, Charlottetown is a prototypical small city.

Walking within its small downtown, alongside the offices for Electronic Arts and a Starbucks on Queen Street (its ceremonial central axis terminating at the harbour’s edge) it was a pleasant surprise to be greeted by strangers passing on the side streets mere steps from the main thoroughfare. For Charlottetown is the archetypal small city at its best, and perhaps represents the best Canadian exemplar of the ancient Greek polis, with its downtown streets home to both its city hall and legislative assembly—their Members of Parliament living on the same streets as their provincial and municipal counterparts.

Founded in 1764, Charlottetown is perhaps best known as having been the site of the famous pre-Confederation meeting in its Government House in 1864, an event which would directly lead to Canada’s Confederation in 1867. What is perhaps less known is that after having laid out many New World settlements, Charlottetown was a chance for the early town planners and surveyors to learn from their past mistakes. After the site was selected in 1765, the general surveyor Charles Morris was sent from Halifax to tackle the task of laying out the capital city for what was then called St. John’s Island—the name Prince Edward Island would not be adopted until 1798.

On his heels came Thomas Wright, who expanded Morris’ ideas in 1771, laying out 500 building lots of equal sizes, with wide streets running north from the harbour, four public squares, and a central square for government, court, market, and church. Unlike most of the other major (small) cities in the Atlantic Provinces—such as Saint John, St. John’s, Halifax, and Moncton—Charlottetown remains one of the few where the church spire continues to be the tallest and most dominant structure in the city’s skyline, not unlike a small city in Europe.

Having traveled often by ferry to the island when I was growing up in the Maritime provinces, I was pleased to see the city is currently going through a renaissance made possible in part by its 12.9-kilometre Confederation Bridge linking it to the rest of Canada, as well as its new cruise ship terminal now receiving up to 80 ports of call a year. The new influx of cruise ship tourists has necessitated the transformation of the waterfront between the terminal and downtown—similar to the transformation of the port city of Saint John in New Brunswick, host to last year’s RAIC Festival of Architecture. Many new amenities in Charlottetown include a love-lock gate and public piano to play along its waterfront boardwalk.

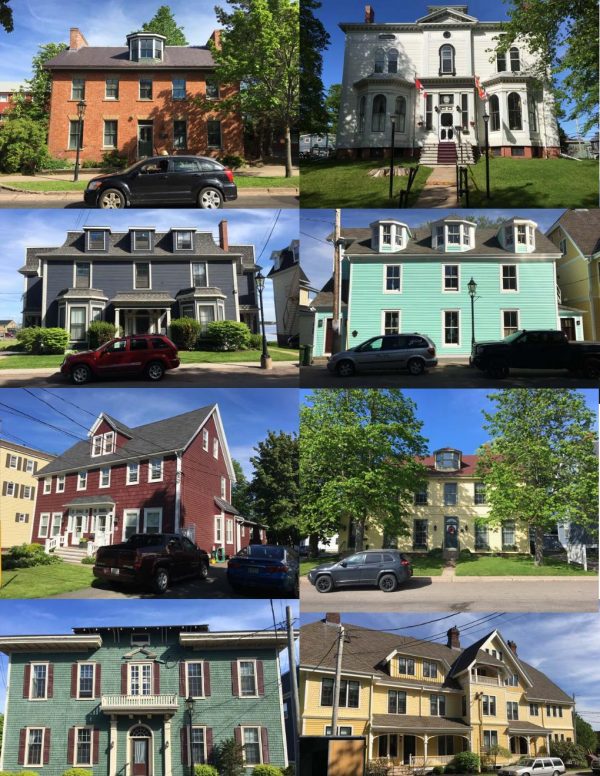

But without question, the true treasures of Charlottetown are the plentiful and multi-coloured wood frame houses surrounding the downtown, locked in time perhaps like no other city. With a few notable brick exceptions, such as the Merchantman and former CPR train station and roundhouse buildings, the remaining building stock in Charlottetown are still as they were originally laid out in 1771, with its original inner-city building fabric still intact and predominantly made up of the Edwardian and Queen Anne-style houses popular in their day.

As for the municipal and provincial buildings in the city centre, as would be expected they decry the predominantly British, and later Loyalist, tastes of the time—the American Colonial style for Government House, now home to the province’s Lieutenant Governor, and Neo-classicism for the Province House, the seat of the provincial legislature. For the city hall, a slightly more progressive architectural style was opted for with the selection of the Romanesque Revival style, built in 1888. And in 1964, the Brutalist style Confederation Centre of the Arts opened in the downtown core, designated a World Heritage site in 2003.

While in Charlottetown, the RAIC Board had the good fortune to sit with the president and members of the Architects Association of PEI and have a frank discussion about how the city is faring now that the Confederation Bridge has been open for two decades, along with the weekly arrival of cruise ships over the summer. With a modest cruise ship terminal capable of mooring up to two ships at a time, I believe there is a great opportunity for the development and design communities to collaborate and realize a terminal more distinctive than the simple decorated shed currently provided, complete with requisite gift shops and free wi-fi.

There is also the opportunity, I believe, for a new PEI chapter of the RAIC to promote architectural excellence and design in Charlottetown, perhaps by offering architecture history walking tours in which an added layer of the city’s history could be provided, told through its architecture—perhaps even showing those already converted to Anne of Green Gables that a new perspective on the island’s heritage architecture is possible, one that also includes the city’s pre-colonial past, beginning with the history of its Indigenous population, as it rightly should. And by speaking to the numerous architectural gems that surround the city centre, a newly established local RAIC chapter network could momentarily distract the tourists from their smartphones, to see with eyes that do not see.

What was most astonishing to learn from the president of the AAPEI was that while Charlottetown may be the political and economic centre of the island, it is surrounded by 44 smaller, rural towns in which the remaining 120,000 residents on the island live. This makes it the most densely populated province in Canada despite it also being the smallest. And with much of the province being made up of the traditional lands of the Mi’kmaq, truth and reconciliation is ongoing in this province just as it is across the rest of Canada, with the exception that the Maritime provinces have an even more complex history than their younger, western counterparts.

It is important now more than ever that we advocate for the responsible design of our built environment, along with good stewardship in the construction and maintenance of our buildings, especially those constructed over two centuries ago, like many in Charlottetown. With the vast geographical expanse of Canada, the regional directors of the RAIC have the ability to advocate from coast-to-coast, and with the launch of a new chapter and network model there is a real potential to actualize in the public imagination the value that architects and architecture can contribute to mitigating, and perhaps even overcoming, our current climate crisis.

***

Sean Ruthen is a Metro Vancouver-based architect and writer.