Can city design be good? Few would doubt that they can, yet an honest answer must be tentative. It must pry into city planning, objectives, and the relations between objectives, reality, decisions, designs and achievements.

So started the essay Quality in City Design written by well-known urban theorist Kevin Lynch in 1966. The piece is a wonderfully candid and comprehensive discussion about the city-wide planning and the complex variables that necessarily intersect to produce a city plan of value. In the end, he could still give no definitive answer to his initial question: a testament to the type of problem the city is.

Given that the piece was written over half a century ago and the explosive knowledge we’ve gained since that time, one would assume that Lynch’s insights would be either out-dated or significantly expanded upon. Sadly, this is not the case. His work is equally relevant now and cities—their design, governance, and processes—remain a baffling puzzle, despite millennia of history.

As the local and global impacts of cities increase, however, it is that much more important to clearly outline what we know about city planning, as Lynch did in his time, in an attempt to inform good decision-making. This is particularly relevant now as many cities, including Vancouver, are attempting city-wide plans.

Within this context, this series will attempt to answer a similar question as Lynch, reframed for the present: Is it possible to create a good contemporary city-wide plan, and if so, how? It will aspire to be as eloquent, candid and succinct as Lynch and use his original framework as a scaffold. I will have succeeded if, by the end, it shows why someone who dedicated his life’s work to the understanding of cities failed to answer such a seemingly basic question.

What is a city?

Those of us who live in cities seem to believe we understand what they are, so this is a worthwhile place to start. A quick search to find the definition of what a city is results in a very foggy journey into vague words. In truth, the term ‘city’ is an arbitrary category used to differentiate diverse settlement types ranging from a small grouping of dwellings to the expansive megalopolis and beyond.

The “city” lies somewhere within this continuum and our inability to clearly describe its attributes and how it works underscores the intense challenges of city-wide planning and design, in general, let alone good planning and design.

Of particular relevance now, and relating to the topic of defining the city, is the issue of boundaries. Countless ancient cities had walls and structures defining their limits explicitly. This delineation made the physical distinction between “city” and “non-city” clear but also masked the fact that most, if not all, didn’t function economically, politically and socially in full isolation.

Here, even in these very early days of cities, we see the seeds of a fundamental challenge to city-wide planning: the city is more than a physical artifact. Well-known urban historian Lewis Mumford once wrote:

The city in its complete sense, then is a geographic plexus, an economic organization, an institutional process, a theater of social action, and an aesthetic symbol of collective unity.

And this does well to give us an inkling of the breadth of what the city is. It’s a built environment. A network. A process. A social theatre. An aesthetic artifact. A symbol. And many others can be added. The city is an infrastructure. A type of media. A creative engine. An ecosystem. The list goes on.

Does this really relate to the nitty-gritty of planning and designing a city? Definitely. The definition of what cities are and how they work is now more ambiguous than ever. Cities are increasingly co-dependent and systemic—that is, they are interconnected across diverse scales, overstepping legal municipal boundaries.

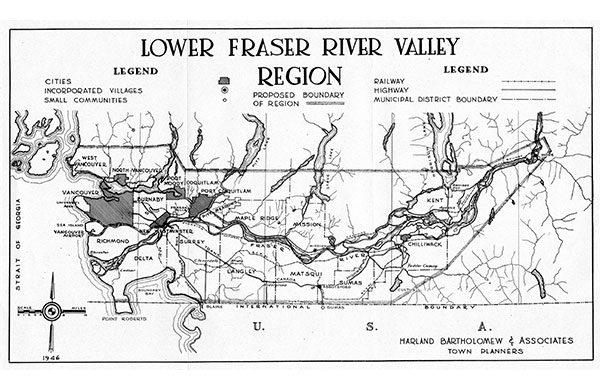

Can one truly consider the City of Vancouver, for example, in isolation from its surrounding municipalities? The lived experience of the city doesn’t end at its official city limits. As a very mundane example, I’m fortunate enough to live in a wonderfully walkable Vancouver neighbourhood that I take full advantage of. However, I play hockey in Burnaby, ski on the North Shore, work in Richmond and UBC, and hike regularly throughout the Lower Mainland, the Fraser Valley and Fraser basin. My private practice takes me all over the Lower Mainland and beyond…let alone my regular visits to friends and family at the other end of the country.

Moreover, cities are tied to global economic and social networks that affect daily life. Let’s look at a popular current municipal example, housing affordability. Although its impact is highly localized, the issue is intimately connected to global flows of money and capital. Yes, certain steps may be taken at the municipal level to temper its effects, but long-term solutions are necessarily multi-scalar and complex. The massive explosion in social housing of decade ago resulted, not from a singular municipal intention, but from the intricate alignment of greater social values, economic wealth, political backing and financial mechanisms, to list just a few of the elements.

The above serves well to ground us in the contemporary reality facing those endeavouring to plan a city. Simply put, current urban environments are increasingly and unpredictably complex. They are part of an expanding and interconnected social, economic, environmental and physical system, and are continually changing and ill-researched because there are no historical precedents. Where five cities reached a population of one million people between the first urban settlement thousands of years ago and 1800, we now live in a world where cities over five million people are a dime a dozen.

With this as a foundation, Part 2 will look more closely at common planning initiatives and their relationship to contemporary city-wide planning processes.

***

In case you missed it:

- Planning City-wide: A Primer – Part 2

- Planning City-wide: A Primer – Part 3

- Planning City-wide: A Primer – Part 4

- Planning City-wide: A Primer – Part 5

- Planning City-wide: A Primer – Part 6

- Planning City-wide: A Primer – Part 7

- Planning City-wide: A Primer – Part 8

**

Erick Villagomez is one of the founding editors at Spacing Vancouver and the author of The Laws of Settlements: 54 Laws Underlying Settlements across Scale and Culture. He is also an educator, independent researcher and designer with personal and professional interests in the urban landscapes. His private practice – Metis Design|Build – is an innovative practice dedicated to a collaborative and ecologically responsible approach to the design and construction of places. You can see more of his artwork on his Visual Thoughts Tumblr and follow him on his instagram account: @e_vill1.