One of the sturdiest tropes of political rhetoric and punditry is that elections, especially those that end minority governments, are a burden. Voters are called upon to engage in taxing behaviours, like paying attention, forming opinions, and getting to a voting station or a mailbox. Apparently, we’re often too busy, irritated or preoccupied to exercise the franchise.

But once in a while, voters really are just up to their ears in crappy distractions — pandemics, climate disasters, foreign policy calamities, etc. – and the adrenalin-sapping rituals of a campaign do legitimately represent one more damn thing. Rightly or wrongly, that’s going to be the asterisk on Election 2021: wasn’t necessary, and perhaps Justin Trudeau and his federal Liberals will pay the ultimate electoral price for their arrogance.

I’d argue, however, that this election is not only necessary, but critically important — an opportunity (in theory) for us to take stock of what we’ve all learned during 18 months of global crisis and apply that hard-won knowledge to the next one, which is, really, upon us already.

It is apparent that the election no one wanted has been dominated by wedge issues (guns, vaccine mandates) and Maxime Bernier’s Deplorables acting deplorably. There’s also been some serious and important debate about affordable housing and daycare, with the latter providing a pretty crisp indication of where the electoral fracture lines can be found.

Yet there’s no question in my mind that the most pressing and urgent matter — the subject that shouts for focus, resources and determination — is climate change. Without dismissing the importance of debates about childcare, etc., climate deserves to be the ballot question on Sept. 20. It is, to paraphrase the old cliché, the emergency in the room.

The case isn’t difficult to make: As of next year, we’ll have about two majority terms of Parliament left before the first Paris deadline of 2030. Canada’s carbon record remains atrocious — with plenty of blame to be apportioned – and it is simply impossible to ignore our contribution to global warming, both here and abroad, via our energy exports.

We tell pollsters that the climate crisis is one of our top-of-mind issues, yet we are far more equivocal when asked if we’re prepared to make sacrifices to confront it. Trudeau’s minority Liberal government has advanced a somewhat ambitious plan, but it’s nowhere close to being sufficient, and their record includes highly problematic choices, like pipeline investments. In the next few years, Canadians will need a government that’s willing to make difficult and unpopular decisions to respond to warming, just as the current government made difficult and unpopular decisions to confront the pandemic.

The lessons about the connection between these two disasters is obvious.

In so many ways, we weren’t ready for Covid-19, and thus one of the critical learnings from the last 18 months is that we need to become much more prepared to respond to the catastrophic implications of warming that we’ve seen play out in the past several months. Attaining that kind of readiness requires a strong electoral mandate.

The climate platform contrast between Justin Trudeau’s Liberals and Erin O’Toole’s Conservatives can be distilled to a few key details: $170/tonne for carbon by 2030 (Liberals) vs $50/tonne and an immediate roll back to $20 from the Conservatives. In winning the leadership, O’Toole talked a lot about how a Conservative Party that doesn’t confront climate can never win. But his platform — and indeed the party’s hesitation when it comes to endorsing climate science –reveals both ambivalence and a lack of seriousness. How else to characterize a gimmick like the Personal Low Carbon Savings Account? That scheme is not policy. It’s an electoral tactic.

Beyond these top-line details, the Tories’ platform still expresses the fantasy that there’s an economic future for western Canada’s oil and gas sector, which accounts for 10% of the economy but scarcely 0.1% of all jobs in the country. The rapid acceleration of the electric vehicle market, plus a growing number of jurisdictions promising to ban internal combustion engines, suggests clearly that this sector’s days are numbered, and the heady era of $100/barrel oil will never return.

In the U.S., which is the destination for so much of our exported energy, the Biden Administration’s highly ambitious climate policies (e.g., a new plan to boost solar from 4% of generation to 40% by 2030), plus a range of other regulatory reforms targeting the American electricity sector, further doom the future of the oil patch.

Several years ago, former Bank of Canada governor Mark Carney began warning of the huge financial risk of “stranded assets” for the fossil fuel sector — essentially, large identified reserves that are accounted for on the books of these giant corporations, but will have negative value as energy markets go green. This scenario no longer seems either unlikely or especially remote. Giant institutional investors are hearing these messages and redirecting their capital.

In other words, Canada faces not just the physical shocks of climate change – more mind-boggling heat waves, deadly forest fires, destructive floods, etc. – but also the imminent collapse of a non-trivial chunk of the economy, the opening chords of which have been clearly heard in Alberta and Saskatchewan in recent years.

A natural disaster plus a social and economic disaster.

One would hope that political parties and their leaders have the capacity to look beyond the next electoral cycle and consider the long-term well-being of their constituents. Sometimes, that outlook requires hard choices, and there’s nothing I can see in the Conservative platform which suggests a willingness to face the facts of 2030 or 2035.

The Liberal and NDP climate plans aren’t perfect, but there’s more in both to indicate a willingness to advance difficult reforms and large-scale investments capable of weaning Canada of its economic and social addiction to fossil fuel extraction – and, to do so before global markets move on, leaving a trail of financial devastation in their wake.

The fundamental lesson of the pandemic is that it is better to take preventative action instead of waiting in a state of denial for disaster to strike. And if it takes an irritating campaign to surface these insights about who can and can not govern through crisis, I can live with that.

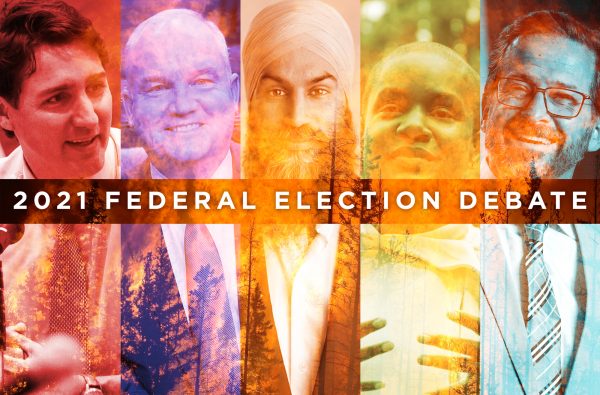

photos courtesy of each party

One comment

That’s the problem: if we make Trudeau pay with his job for this choice, how many of the rest of us end up getting made to pay along with him and in what cost?