We are currently experiencing a noetic turn, from a speech-based to a data-based civilization. In the historical analogue world, the relationship between things, words, and images were irreversible. Today, relationships between data and words, images and sound have become reversible. This media-ontological shift also changes the rules of the game in political semantics.

- Peter Weibel, from the Introduction

Author: Floyd E. Schulze, Jovis Verlag publishers, 2023

If you’ve ever wondered what the Simpson’s house may have looked like had it been designed by Frank Lloyd Wright or Le Corbusier, look no further then graphic designer Floyd Schulze’s newly released Hey Computer! Though diminutive in size—roughly 6″ x 4″, or postcard-sized— it packs a punch with its 400 pages of 343 AI-generated images. Opening with a brief introduction by the head of Design, Data, and Society Group at Technische Universiteit Delft— Georg Vrachliotis—he and Schulze acknowledge much of what we currently understand about generative AI will be obsolete in six months. In the meantime, they do their best to give us a breakdown of where we currently find ourselves in the discussion of AI-generated imagery.

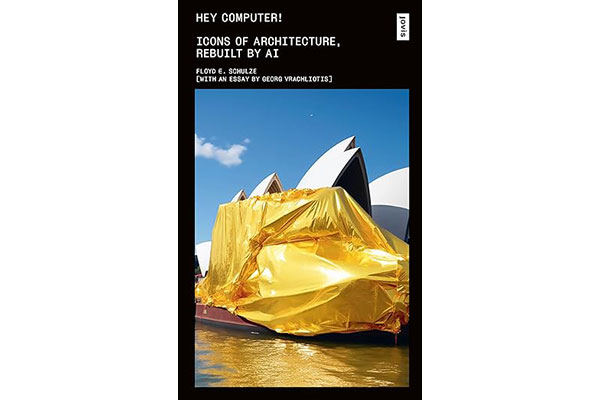

The book’s tongue-in-cheek sense of humour is on full display throughout, which along with the Simpson’s references is joined by several AI-generated images in the style of Monty Python. While the book’s money shot on the cover is the Sydney Opera House in the style of Christo, the greatest hits of architecture are here more or less chronologically, from Art Nouveau to High Modernism, from Bruno Taut to Frank Gehry. Given how easy it has become to generate imagery, it is clear what a tremendous exercise it must’ve been to edit what is found within.

Broken into five chapters, Schulze explains that he used three different AI tools for the book’s contents—Midjourney, DALL-E, and Stable Diffusion. The second chapter, BUILDINGS, makes up most of the content in the book, for which Schulze simply asked AI to recreate existing buildings. The results are astonishing, and we are all of course free to try this ourselves, but it is fun to see in condensed form all the greatest hits gathered together like this all the same. I especially appreciated the book’s remaining chapters, CHAOS and DREAMS, in which the author waxes poetic, creating more autobiographical imagery, including the aforementioned Simpson’s houses, of which he provides eight variations by eight different architects.

The book is also in a way an opportunity to explore AI-generated collage. In one instance the author pairs an AI-generated cityscape in the style of Blade Runner next to a similar view in the style of Metropolis. And of course, Wes Anderson is here, with Grand Budapest Hotel rounding out the DREAMS portion of the book. With this much imagery, the book’s cup runneth over, and given the hundred or so iconic buildings the book’s author has chosen for AI fodder, one obviously had to draw the line where to start in architectural history. Ultimately, the book is meant to be a polemic on the current discussion around AI and its impact on architecture, hence the subject matter.

Among the usual suspects you would expect to see here like the Sydney Opera House and Villa Savoye, Schulze touches on the Bauhaus and De Stijl before providing some specific examples of Eero Saarinen and Mies van der Rohe. Frank Gehry on AI here is almost hallucinatory, and the author also explores the moments between modern architecture and sculpture, especially in the AI mistakes generated along the way, which he admits were often better than the original. Knowing that everything here on display has been 100% sourced from the public realm is breathtaking and provides the foothold for Vrachliotis’s introduction, entitled “Lost Image and New Vision”:

“We find ourselves in a challenging yet historically fascinating moment: on the one hand, we are increasingly losing control over digital image production and organization in architecture. On the other, we are acquiring new data-driven forms of visualization. The loss of one is perhaps the gain of the other.“

All Monty Python kidding aside, the serious discussion here focuses on the need to perhaps press pause on AI-generated imagery before creative industries like ours can work out the devil in the details. Architects have always been the generators of possible worlds, and Midjourney and Stable Diffusion are just new tools like AutoCAD and Revit when they appeared several years ago. Our profession will adapt, but we need to proceed cautiously. As Schulze quotes Marshall McLuhan in the book’s opening pages, “We shape our tools and thereafter they shape us.”

Several years ago, semiotician Umberto Eco penned Foucault’s Pendulum, in which the book’s protagonists use a recently acquired word processor—new tech in 1988—in order to combine all the occult knowledge of their day to reveal the philosopher’s stone. Currently, we find ourselves in a similar Pandora’s box moment, with more uncertainty than ever about what AI will unleash on the world. It is obvious that if it can be harnessed for good, McLuhan’s idea of a tool that shapes the world may seem less malevolent and more altruistic, much as the architectural image has served the design profession since time immemorial.

***

For more information of Hey Computer!, visit the Jovis Verlag website.

***

Sean Ruthen is a Metro Vancouver-based architect.