For the past two decades, Spacing contributor Sean Ruthen has written several architectural travelogues on places near and far – here in Canada from Calgary to Charlottetown, and in Europe visiting Barcelona, Amsterdam, and Rome. In this latest in the series, he visits several new and old architecture destinations in London, with stops at Bath and Windsor/Eton along the way.

To visit any city is to visit its history, but in the case of London it is a gross understatement to say its streets are dense with it—applied in equal portions to its buildings and people. To visit the city, along with millions of others over the summer months, you need to mind your step. With a metropolitan population of 8.9 million, it has over twice that visiting annually as tourists, something I can now personally attest to having just spent part of July there, mercifully ahead of schools getting let out for summer vacation.

Trafalgar Square, Covent Gardens, Picadilly Circus, and the South Embankment were jam-packed with tourists and locals alike, a dizzying display of humanity I had never seen before in the city. With only a few days in London to see a carefully curated shortlist of stops—the Sir John Soane museum, the Victoria & Albert museum, and the Serpentine pavilion—everything beyond that was extra sauce.

As it turned out, this bonus material would include a visit to the Sky Garden atop the late Rafael Vinoly’s 35 Fenchurch Street tower—known to Londoners as the walkie-talkie building—along with a stroll by Inigo Jones’ Queen’s House, now Royal Navy Academy, as seen from the Greenwich observatory with Canary Wharf behind. Other highlights included visits to both the Tate Modern and the British Museum.

Moving from bonus to sublime was Evensong at St. George’s chapel in Windsor under the High Gothic tracery, listening to the choir and organ interplay with the architecture. Equally divine was a stay in the home of a former British PM, William Pitt the Younger, whose five-storey rowhouse in Bath was built at the same time as the city’s great Crescent and Circus.

But perhaps the biggest surprise of all was the Sir John Soane museum itself, which even having seen pictures could not prepare me for the visceral sensation of being there, face-to-face with so much history. While several large rooms where he and has family had lived remain, the museum portion of the house is in an exercise in restrained archaeological layering, such that pictures of the central space can simply not do it justice. It is said his students from the Royal Academy would come to study the artifacts and occasionally archive a newly curated piece for him.

Densely packed into a London rowhouse in Holborn, the museum and former home of Sir John Soane is an exquisitely curated collection of over 10,000 objects which he collected and stored in his house, including a great Egyptian sarcophagi which is the museum’s centerpiece. As a professor at the Royal Academy teaching arts and architecture, Soane was also a working architect who was official architect to the Office of the Works. Having designed Whitehall along several other notable structures, Soane designed his rowhouse along with the two adjacent ones, allowing the rent collected on his neighbours to provide for an endowment to leave the museum to.

Compared to other London tourist stops, the Sir John Soane Museum welcomes a modest 100,000 visitors every year according to its website. Modest that is when compared to the British Museum, which sees 6 million visitors a year, along with our next stop—the Victoria and Albert Museum. Housing some 2.2 million works of art, the V&A museum welcomes over 3 million visitors annually.

With so much on offer, from whole wings solely dedicated to silverware and stained-glass (the tapestry section was closed), one had to contend oneself in the space of an afternoon to selectively sample from the 12.5-acre site. Much like the Louvre and British Museum, its contents are for the most part displayed chronologically. However, good manners go out the window in the museum’s great central hall—called the Cast Courts—two massive glass barrel-vaulted atria built to display two full-scale plaster recasts of the famous Trajan column in Rome.

Housing ancient classical statuary, renaissance painting, and sculpture, alongside religious altarpieces from both Gothic and Romanesque periods, all are careful reproductions made for study and contemplation. While photos were permitted while I was there, there were also many sketching the art, a living testament to the public amenity that Victoria and Albert had wished it to be. And where else can one go to see three full-scale Michelangelo reproductions all side by side—David, Moses, and the Madonna of Bruges—all being watched over by a reproduction of Raphael’s School of Athens.

Not too far from the V&A is Kensington Gardens, host of the final stop on my architectural bucket list—the Serpentine Gallery. Having visited two previous Serpentines—Frank Gehry in 2008 and Sou Fujimoto in 2013—I must say the 2024 one will go down as the most Spartan ever, as designer Minsuk Cho’s Archipelagic void treads so lightly that it might blow away. A geometric play of triangles and circles in plan, function takes precedence to house the pavilion’s requisite program—a cafe and library, along with a two-storey play structure.

Following our visit to Kensington Gardens, we had the good fortune to see the view of the city from the Sky Gardens at 35 Fenchurch Street, the observation deck of which is open to the public (with pre-booking naturally), along with a restaurant called the Darwin.

The view is breathtaking. A higher vantage point open to the public than the Eye, from the top one can see all of the city’s history—from the Tower of London and bridges along the river, the CBD to the north including the Gherkin & Lloyd’s, St. Paul’s Cathedral to the west, with the Globe theatre, Tate Modern and Shard to the south of the river, and a bit further off to the west the towers at Canary Wharf.

One last stop before leaving London: the addition to the Tate Modern, new since our last visit in 2011. Built close to two residential towers immediately adjacent, despite the background noise we could still appreciate the material and spatial richness that I encounter in all of the Herzog & deMeuron buildings I have had the good fortune to visit (with the Tate Modern several times now).

While there was no major exhibit to see, the main event has always been for me the building itself. With the main gift shop now moved to the new tower’s base, the new gallery space to the south of the original power plant footprint is crossed by a series of pedestrian bridges to the main building, a new experience for the gallery visitor.

With time for one last-minute stop at Trafalgar Square and the National Portrait gallery, we were finally off to Bath, to escape the hectic city for the country, going to perhaps one of the country’s oldest and most famous spa destinations.

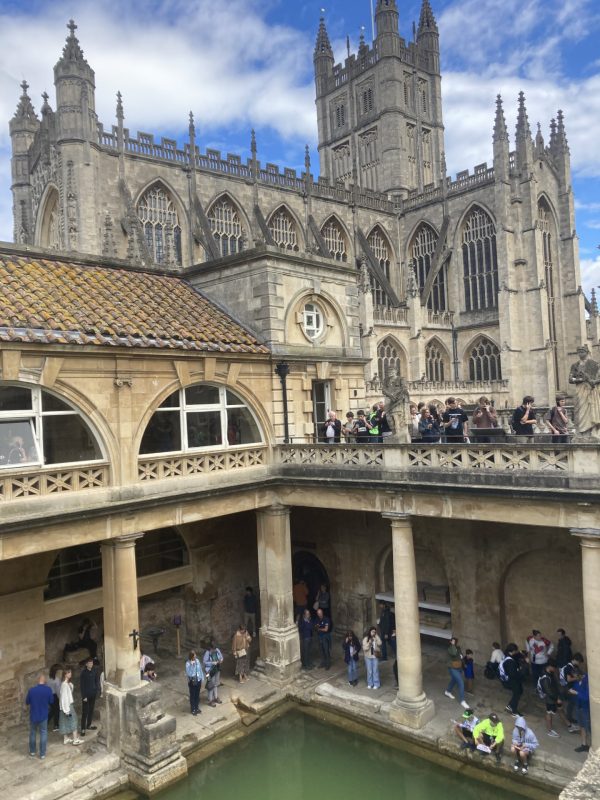

Without a doubt, a visit to the Roman baths is mandatory, as it helps one come to terms with the notion that one million litres of hot water a day has been coming up out of the ground at this location since as long as there has been recorded history. The Druids had since time immemorial called the place sacred before the Romans built it up in the first century AD, at which time they erected a twenty-metre-high barrel vault over the main bath.

After the sacking of Bath and the collapse of the barrel vault in the Dark Ages, it was rediscovered again in the 1750s and rebuilt to the extent that it is seen by the general public now. The columns are not from Roman times, however. They are Georgian, named for the king who commissioned the work. This included much of what we think of as now Bath, the layout of its streets with its Abbey, along with the construction of the Crescent and Circus, whose neo-classical architecture is a wonderful reproduction of Palladian Renaissance Italy.

Bath is built on the Thames, but with weirs to manage the water—the city is built in a bowl in the landscape, and one of its most charming moments is a Ponte Vecchio-style bridge over the river, the only bridge with shops on it in all of the UK. It has been recognized on two occasions as a World Heritage Site by the UN as a place on our planet where history has collided with our natural world – the baths – and where in 60 AD the goddess Sulis of the ancient Druids merged with Minerva, goddess of war of the conquering Romans.

Perhaps at times like these, set in divine places of nature, we can for a brief moment forget our differences.

***

Sean Ruthen is a Metro Vancouver-based architect.