In the past decade, a term has been tossed around to describe a generation who began coming of age in the early 2000s. Called the “Millennials”, this group is comprised of those born between 1981 and 1999, many of which grew up in the age of technology, with little or no memory of a time before computers existed. The term is often used in a derogatory manner by generations past, referring to them as lazy, entitled and unwilling to work hard for success. Regardless of their perceived behaviour, this large demographic, currently making up 32% of Canada’s population, is causing city planners and transit authorities to rethink previous mobility trends. With a large majority of the 19-34 years old migrating to city centres, we are witnessing a shift from the suburban, car-centric models to one focused on densification and multi-modal transportation. So just how is an entire generation creating new demands, specifically around how cities move people?

Disclaimer: I feel it’s important for me to note that – as someone born in 1980 – I consider myself an early Millennial, and as such draw many parallels to the choices made by those in my age group.

There are some key factors that have led to the growing need to adjust city and transit planning for Millennials, namely: education, employment and lifestyle choices. Each of these important aspects of Millennials’ existence play a large role in the places they choose to live and the way they move. Currently, the greatest changes are being seen in large urban centres, mainly because these are the most desirable locations for young people. In Vancouver, where I have settled with my husband and our two young children, Millennials makes up 27% of the population — only slightly higher than Toronto, Montreal, Ottawa and Calgary. This means city planners have had to start recognizing and compensating for this large influx of people, making changes to meet their needs and ensure the success and growth of the city centre.

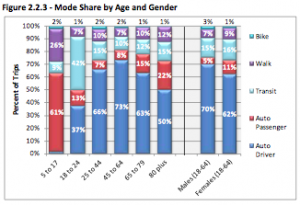

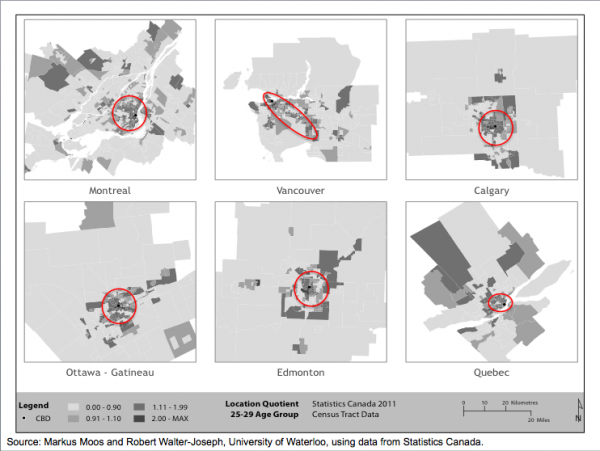

Most Millennials are doing just what their parents had hoped for — striving for higher education to earn the knowledge and experience necessary to pursue their ideal job. With many universities and colleges located in, or just outside major city centres, it becomes clear why there is a growth in the number of Millennials living in the city. However, because they are focused on their education and the stress that entails, their choices for dwellings centralize near to their schools or along transit lines. Commuting by car is unrealistic on a student budget, with the rising cost of gas, insurance and regular maintenance on their vehicles. So most opt for other more affordable means, most notably public transit (See Figure 1). City and transit departments have recognized this trend, working to find solutions to moving such a large number of people. In Toronto, this has meant the construction of the York University subway station, aiming to relieve the over-crowding currently experienced on bus routes serving the university. Here in Vancouver, the same is being proposed for the Broadway Corridor, linking Commercial-Broadway Skytrain Station (the busiest in the city) with the University of British Columbia, a route currently served by an express bus line that is over-capacity both in terms of passengers, and available buses.

Figure 1: The Mode Share and Trip Rate by Purpose by age shows the highest use of transit for ages 18-24 and with majority of trips made to get to work or school (Translink 2011 Metro Vancouver Regional Trip Diary Survey)

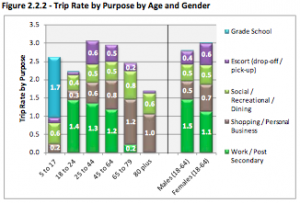

Similar trends are also noticeable once these young people enter the work force. With the Boomer generation working longer and later in life, there are less full-time, permanent employment opportunities available to Millennials. Generally they earn less, and work in flexible, contract jobs, many making annual incomes under $24,000. This is hardly the generous income needed to make many of adulthood’s previously sought-after investments — most notably personal vehicles and home-buying. Those that choose to stay in the city do so largely in part to remain within a short commute to work, resulting in an increasing number of young people choosing to rent in mid-rise dwellings, many times with friends to help share the expense. Their chosen locations also have a lot of do with proximity, meaning the most densely populated areas tend to focus heavily in locations where public transit is available, along transit routes that move people in and out of the downtown core where most young professionals go to work during the week, and for play on the weekends (See Figure 2).

Figure 2: Location maps indicating highest population of 25-29-year-olds in Canada’s major cities. See Dr. Markus Moos explain.

But aside from education and employment, the largest drivers of change for mobility in cities are the inherent life choices made by Millennials. Because they are young, many still single, they are incredibly social and need the city to facilitate their need to feel connected to their peers. Living in city centres is one way they achieve this, by staying “close the action” and able to enjoy getting together with friends after work, relaxing on the weekends at local parks, and enjoying the sociability only city living can provide. Their mobility choices reflect this greatly. In general, Millennials are pragmatic — they will choose the housing and transportation options that are most convenient and meet their needs. This explains why many enjoy multi-modal transportation options instead of relying on just one.

Public transit offers a low cost option while also allowing them to stay connected and social with friends on their way to, and from their destinations. Although often referred to as being anti-social, those Millennials seen entrenched on their mobile devices are not doing so to ignore the world around them, but instead use the time in transit to catch up on emails, text with friends to plans their evenings, and maybe even connect with family members living at a distance. They choose transit because it’s convenient and facilitates making the most of every moment in their busy lives.

Increasingly, Millennials are also beginning to make up a large number of the cyclists on the roads. A bicycle is an inexpensive means to get from point A to B, and in large, traffic congested cities, it is often also the most convenient way. Some cities are reacting to this increase in bike traffic and offering safer infrastructure to them. Vancouver has experienced a slow increase in the number of kilometres of separated cycle tracks offering safe connections from bedroom communities, like my own in East Vancouver, to the city centre. In Calgary, a city with one of the highest densities of 19-34-year-olds, not only are they improving public transit, but they have recognized the need for comprehensive bike infrastructure and are currently constructing a complete grid of bike lanes in Calgary’s downtown business district, set to be completed in spring 2015.

Another means of public transportation that has experienced increased popularity, largely in part to Millennials, is the car share scheme. While studies are showing that the number of young people getting their drivers licence is dropping, there are still those who have them. In my household, we decided to shed the excess baggage car-ownership brought with it over four years ago, selling our car and taking full-advantage of our local car co-op, Modo, and Car2Go. Car share schemes offer the convenience of car travel when needed, like hauling large items or making that big grocery shopping trip, without the inherent residual expenses that go along with owning a car — gas, maintenance and insurance — each of which is included in the attractively low fees. Once again, it becomes a pragmatic choice: what will get me where I need to go with the most ease and least stress.

It is an exciting time right now in urban development, and the habits and behaviours of Millennials are helping to push change along. While these changes are not always welcome by generations of years past, it is integral for city and transportation planners to recognize this growing need. Not simply because the demand exists, but also because the changes are building habits that, obvious or not, understand that a car-centric model for large urban centres is unsustainable. Cities are growing faster than ever, and it is impossible to facilitate the amount of space that would be needed to move people if everyone traveled by private automobile. While one of the main motivations for a young person to choose public transportation is the financial implications, their need is creating a silent revolution. The next step will be maintaining and promoting these patterns as they start families, and their needs change once again.

Editor’s Note: Part 2 of this series will explore how current changes in habits will effect the suburban or dispersed city’s approach to transportation, as Millennials enter parenthood and mid-life, and consider leaving the city centre.

Melissa Bruntlett lives and works in Vancouver, BC with her husband, Chris and their two children. Melissa, with Chris, co-founded Modacity, a multi-service consultancy, focused on inspiring healthier, happier, simpler forms of urban mobility through words, photography and film.

Top photo by Rick Forgo; Other photos by Chris Bruntlett

The Cities For People features are a project between Spacing and Cities For People

4 comments

It’s all very well to talk about young folks living in the city and using transportation other than a car. But what happens when they decide to settle down and raise a family? Condos in the city centre are expensive and usually quite small. Houses with lots are even more expensive. I live in a small row house in central Toronto and the prices for a similar house are $600,000 and up, prohibitive for a young couple starting out.

David, please stay tuned for part two when I discuss exactly what you are talking about. This piece is simply a reflection on what is currently happening in major city centers.

They live in a surburan town Centre townhouse or larger condo in a walkable transit connected neighborhood but have to commute a longer distance. Instead of being a 2 car family only have one car and commute by transit or electric assist bike? That’s what I do.

Great read and some salient takeaways. Having 42% of young Canadians aged 20-29 living at home rather than solo presents as many opportunities as it does challenges.