Sited at the LaHave River estuary on Nova Scotia’s Atlantic coast, where Samuel de Champlain made his first landfall in the new world in 1604, the Ghost Architectural Laboratory was started in 1994 by Brian MacKay-Lyons. In its thirteen iterations, it served as an international education center in the building arts, as well as a constructive critique of contemporary architectural education. The resulting campus, built in and around the foundations of previous structures, is an expression of utopian architectural ambitions, constructed with the most modest means. As MacKay-Lyons notes, “By ‘listening’ to the site’s rich history and local material culture traditions, the Ghost Lab is a built critical regionalist argument.

– Excerpt from the book

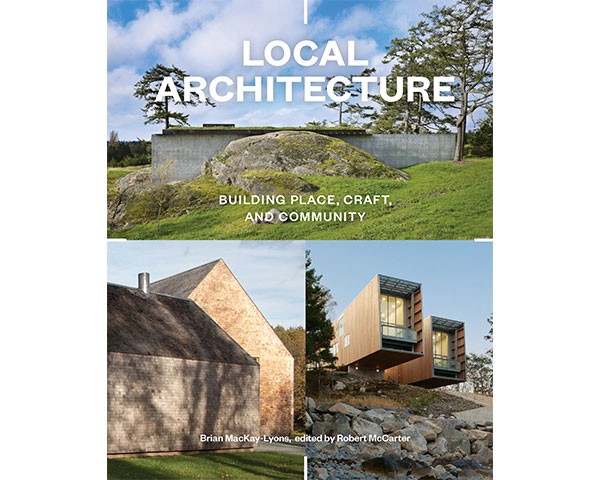

Edited by Brian MacKay-Lyons & Robert McCarter (Princeton Architectural Press, 2015)

As a student at the Dalhousie School of Architecture – when it was still known as the Technical University of Nova Scotia or TUNS – I had the good fortune to have met the then 37 year old Brian MacKay-Lyons. He had already been teaching at TUNS for ten years, and had just opened his own small architecture office, a few years earlier. Unbeknownst to me at that time, and with the school about to build an addition designed by him, he was struggling with the state of architectural education and how to teach it. He felt that the divide between education and practice was growing more and more every day, causing him to become disillusioned. This, coupled with his sense of powerlessness to reverse this trajectory, had brought him to the verge of walking away from teaching entirely.

As he points out in his new book Local Architecture – Building Craft, Place, and Community, it was his founding of Ghost Lab in 1994 that brought him back from the edge, enabling him to reestablish the connection between architectural education and the process of making – something he felt had been very much missing from the architecture schools of that day.

And so for the next twelve years, those Dalhousie architecture students lucky enough to get into his studios would be whisked away from their computers and drafting tables in Halifax, to work with their hands building structures on MacKay-Lyon’s farm in Upper Kingsburg, overlooking the bay where Samuel de Champlain’s ships weighed anchored, some 400 years earlier.

Over the course of the studio, students were taught to see the subtle relationship between the craft of building with local materials, culminating in one three-day event at the end of each semester, where Brian invited well known architects to speak to the students in a small round barn on the property. Most came to speak about their modest practices, but more they came to speak of the means by which they connected the material and economic reality of their day-to-day work, with more culturally significant ideas about community and craft.

Local Architecture is then, for the most part, the story of the last of these thirteen student workshops, at which many notable Ghost alumni were invited back to speak. Most notably, however, its point of departure is the keynote presentation given by the three architectural heavyweights invited – Kenneth Frampton, to give an update on critical regionalism; Juhani Pallasmaa, positing the notion of a metaphor for sustainability; and Glenn Murcutt, giving a presentation of his Pritzker Award winning architecture.

Also invited to present were the principal architects of eighteen small architectural practices from near and far, rounded out with two hundred lucky members of the larger architectural community, invited to attend as witnesses to this last great hurrah. In the book’s first introductory essay entitled ‘Seeing the Whole World’, Thomas Fisher poignantly summarizes the three key themes for the last and greatest Ghost Lab – Place, Craft, and Community – and how MacKay-Lyons created each day for one of the keynote speakers to talk respectively on each of these themes, with corresponding present-day practitioners and historians then contributing their own work as a complimentary commentary.

Seemingly following this tripartite narrative, the book itself is likewise broken into three parts, with the essays of the three keynotes presented first, followed by the projects featured by the eighteen practitioners – making up the bulk of the book – and closing with a number of essays inspired by the event, several of them contributed by many members of the Dalhousie School of Architecture faculty. All of this material is bookended by a foreword and afterword by MacKay-Lyons himself, revealing in the latter why he decided to conclude the Ghost Lab project, saying how it was a conversation with Pallasmaa that convinced him it was time.

Past Spacing Vancouver reviews have featured several of the guests Brian had invited to Ghost Lab 13, the Patkaus, Tom Kundig, and David Miller, to name a few. Even Juhani Pallasmaa himself has often visited the faraway shores, and was the subject of a feature article written when he visited Vancouver in 2009 to speak at the Vancouver Playhouse.

It is perhaps for this reason that it comes as no surprise to find this event on the east coast of the country featuring the work and ideas of so many west coast architects, as MacKay-Lyons calls out, and in fact challenges our materially rich, west-coast lifestyle, and how it has created an opportunity for a number of smaller more intimately scaled architecture practices to avail themselves to an intense form of crafting and making – with clients willing to indulge this higher level of craftsmanship in their form-finding.

Ghost Lab then appears on our cultural landscape as a myriad of things – first, and most importantly, as a design studio for the Dalhousie students in the tradition of the Bauhaus. Second, but no less important, it challenges the modern conventions of architectural education, how students and university curricula are becoming increasingly drawn into the lure of technology, placing too much emphasis on architectural representation and not enough on the bigger picture, i.e. the built environment.

Lastly but not least, Ghost Lab figures largely as a symposium of current thinkers and practitioners, much like the CIAM and Team 10 were vehicles for important discussions on architecture in their day.

In the opening pages of the book, Dalhousie architecture professor emeritus Essy Baniassad is quoted as saying, “Don’t let the school stand in the way of your education.” So in this same spirit, Ghost Lab has had to draw to a close lest it become guilty of becoming so much institutionalized navel gazing. This awareness of the fragile relationship existing in architecture between learning, teaching, and practicing is perhaps Brain MacKay-Lyon’s greatest contribution to the design world.

For this reason and many more, Local Architecture is a must read for the architecture student, educator, and practitioner alike. Culturally, the book is a commentary on how the state of both the profession and teaching of architecture continue to battle the slings and arrows of globalization, accompanied with essays by some of the profession’s most prominent thinkers, and interspersed with a handful of projects featuring several of the profession’s most inspirational form-givers.

The questions around ‘what shall we build, now that we can build anything?’ was a central focus of past Ghost Labs. It is telling then that at this final Ghost Lab, MacKay-Lyons would also add ‘what shall we teach?’

***

Sean Ruthen is a Vancouver based architect and writer.

One comment

Local Architecture will be available at the Toronto Public Library soon. Click here:

http://www.torontopubliclibrary.ca/detail.jsp?Entt=RDM2993665&R=2993665

to put a hold on this book now.