Students conducting an active transportation audit. From @APA_Planning/Twitter

Some believe that Canada’s provincial and national urban planning institutes are increasingly moving towards principles of social inclusion and equity. However, a major factor inhibiting the inclusion of young people and others working outside higher paying private and public sector jobs in planning is the institute fees, which can be a serious financial burden. The burden is exacerbated for those with student debt or other barriers to employment.

In Canada and the United States, planners go through an accreditation process that generally involves going from being a student in planning school, to a pre-candidate once they graduate, to a candidate once they have sufficient experience working in planning, to a full member once they pass a Professional Examination.

Speaking to a series of anonymous sources, it becomes clear that the planning accreditation process is arduous for many. However, as a planner based in Manitoba says, the professional designation process helps protect “the integrity of what it means to call oneself a ‘planner.’

The people interviewed include one young planner working in the public sector in Manitoba, one planner working for a municipality in the Prairies, one planner based in British Columbia as well as a self-employed consultant based in Toronto. The planners interviewed decided to remain anonymous due to concerns that their views would have an impact on their professional reputation.

In Ontario, planning fees for pre-candidates and candidate members range between around $500 to over $700, if members want to join both the provincial Ontario Professional Planners Institute (OPPI) and the national Canadian Institute of Planners (CIP). The consultant based in Toronto says that these fees are “quite expensive at least for recent grads, who don’t have a job and may not have started their careers yet. It’s required for a lot of job applications, so you end up in a catch-22.”

Fees are a barrier across the country. The planner working in Manitoba says he pays yearly fees to the Manitoba Provincial Planners Institute (MPPI) which, unlike the Ontario institute, rolls mandatory CIP fees into its yearly dues (Ontario and Quebec are the only two provinces where CIP dues are not required for members). Paying roughly $498.47 a year, he says he has had to put money aside for the annual fees and the professional exam necessary for full membership to the institute. Furthermore, he states that, if it wasn’t for a fellowship he received during grad school, it would be much more difficult to put money aside for the fees.

Meanwhile, the planner based in British Columbia says that she has paid about $3500 to her provincial institute (PIBC) and to the CIP since 2010. Like many of her peers, she has not had a permanent job in the field for over six years. When asked on the current fee structure, she says “it’s unfair that candidate and provisional members pay pretty much the same as full members, considering we are less likely to have job security, are generally earning less, and we don’t get the same professional benefits as full members.”

The consultant working in Toronto says that Canadian planning institutes should be mapping out where planners tend to end up after graduation. Although the municipal and private sector planning jobs in land use still exist, he has noticed that an increasing numbers of planning school graduates are ending up in non-profits or are self-employed. Compared to older planners in the field, he has noticed more of a social justice mindset in emerging professional planning. Planners galvanized by these issues of equity and affordability may find their traditional planning institutes less relevant.

The planner working in the Prairies certainly does. She has found that her provincial planning institute does not resonate with her interests in social planning. She says: “I would like more formal professional policies advocated for by planning institutes on issues of Indigenous land rights, climate change, inclusionary zoning for affordable housing, transit oriented development and the public good. The profession could have more positive influence in the world but we haven’t built consensus, coordinated ourselves and supported planners to push boundaries and be political in a non-partisan way.”

Despite having now secured stable work two years after graduating from planning school, and now being in a position to afford to pay her annual dues, she is not interested in paying into her provincial planning institute. She would rather pay into the Planners Network, which has a membership fee structure relative to income level, instead of a standard fee structure and is a better fit with her professional ethics. While she is focused on community-based advocacy on planning issues rather than trying to change her provincial institute from the inside, there are examples of planners in both Canada and the United States that have been pushing their planning institutes to reject remaining neutral on issues relating to equity.

George Benson, Master’s student in planning from Vancouver, currently serves as the Region 5 representative on the Student Representative Council of the American Planning Association (APA). Additionally, he is a student CIP and PIBC member, and sits on the latter’s Climate Action Task Force. Benson brings a unique perspective as someone familiar with both American and Canadian planning institutes. He sees opportunities for Canadian planners to learn from the American fee structure. He believes a more generous fee structure for emerging planners is a way of encouraging young people to maintain their membership to their provincial and national institution consistently from the start of their career to when they retire.

In the APA, for example, students receive free memberships for the entirety of their degree. Benson says, “Because I don’t have have pay membership dues there, I can justify paying for them here [in Canada] for PIBC and CIP. If I was looking at APA, CIP and PIBC fees separately, I would be very much so having to pick one over the other.”

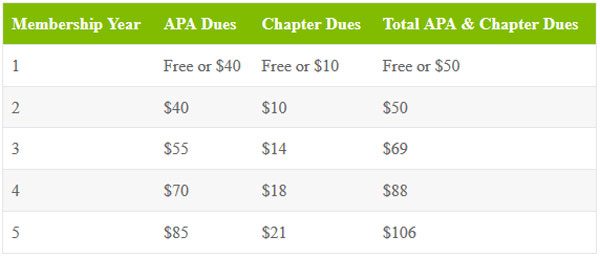

The APA has an Emerging Professionals Program, which takes young people through their planning degree and into their first few years in the field. The program includes access to scholarships, job postings, as well as resume clinics and mentoring at the national planning conference. George emphasizes, “That’s coming at no membership cost [for students].” As students move into professional practice, membership dues at the APA are sliding scale based on yearly income. Meaning that an entry level planner and a director of a city planning department will not be paying the same dues. Furthermore, the APA has divisions for planners in fields related to transportation, women in planning, black communities and disaster recovery. The APA has a broader view of what planning professionals do as consultants and working in community planning, which differs from their Canadian provincial counterparts that focus primarily, but not exclusively, on land use.

For now, the planning consultant in Toronto tells me about the first time he went to the office of his provincial planning institute in Canada. “I was actually interested in the requirements around being certified here in Canada, [and] the fees to apply. It was interesting because I went up to their office in the middle of the afternoon and it was [around] 1:30pm or something, and their office was closed. On a weekday. This was the OPPI office. I didn’t leave with a great experience,” he says.

I hope we will soon see our provincial and national planning institute’s opening up to the needs of emerging professionals. As someone who takes the ethical implication and professional acumen of planning seriously, I am proud to be a member of the APA with the weight and respect that comes with being associated with a planning institute. I am disappointed to see the unaffordable fees for emerging professionals at my provincial and national organization in Canada. The membership fee structure and planning accreditation process is a barrier for those working in the field who want professional recognition and support, while also working in entry level positions and/or community-based social justice related work, which are both unfortunately often underpaid.

Benson says that his experience with the APA drives his optimism that planning institutes in Canada will continue to strive towards supporting students and young planners across provincial boundaries,“I think we can have that [sort of support in Canada]. I’d love for us take whatever steps [necessary] towards that reality provincially and nationally. I know as a profession we will be stronger if we do.”

***

Jen Roberton is a graduate of the School of Community and Regional Planning at UBC, where she focused on public safety planning for LGBTQ2S+ communities and sustainable transportation planning. When she’s not hard at work, Jen can be found exploring nature on her fat bike.