You might remember the ink spilled several months ago over Maria Cook’s Ottawa Citizen article revealing plans for a 10-storey Roxy Paine sculpture, a kind of giant stalagmite atop Nepean Point. Online commentators quickly lashed the New York artist’s Hundred Foot Line, and in the tradition of taxpayer critiques, ridiculed the commission as yet another foreign and aloof New York abstraction pushed onto the “suckers” at the National Art Gallery. Not to be outdone, the curatorial establishment rallied to defend the installation, apparently eager to assume the role of a cultural bastion desperately resisting the philistine masses. (A Mount Carmel complex which says a lot about the gallery’s PR doctrine and its evolution since the early 90s, but let me concentrate for a moment on what seems vital.)

These art controversies may strike us as naive, foolish, or ridiculous, but I believe they present some otherwise unavailable clues or code outlining larger processes in Ottawa’s historical development. More specifically, these public art installations are likely the latest phase in Ottawa’s well-known spatial mutation, beginning in the 1950s, when the horizontal city — the “Edinburgh of the West” whose only towers were the spires on churches and on Parliament — burgeoned into the familiar vertical experience of glass and concrete, the stunted mockery of Toronto or New York. (With all that came packaged: wild architectures; kaleidoscopic visual stimulation, etc.)

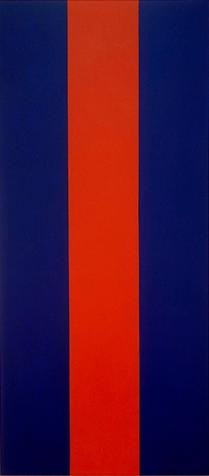

Let me begin by trying to outflank an art establishment which now incorporates public outrage into its media strategies to better neutralize popular indignation (“Still, nothing gets Canadians talking like Voice of Fire!”) The problem, as I see it, is simple. Controversy, even a miniaturized one, allowed the Gallery’s curatorial mandarins and strongmen to short-circuit debate by positioning themselves as the bearers of progress and enlightenment, braving all danger to protect “culture” from the horrors of fire and sharpened sticks. We need reminding that the contemporary art establishment’s own guiding logic — the urge to break out of the “boring” museum and its stifling, dead air — places it on the same plane as the mass-produced cultural junk from which it still, without much justification, claims to elevate or distract us. The point is to remind ourselves that what makes “official” art profitable, its whole excitement or thrill, is precisely the invasion of people’s common space and its illicit appropriation of popular anger as proof of its own value or success.

But I want to suggest another purpose to the dramatic coup d’état at Nepean Point and more generally, to the whole catalogue of chaotic architectural transformations in Ottawa and elsewhere. I believe we are witnessing the spatial byproduct of a civic demolition project at work since roughly the late sixties, with the corporate art-products celebrating a new global system emerging from the compost heap of decomposing nations. (Otherwise one is at odds to explain why art sponsors prey so voraciously on civic temples and heritage buildings. Take I. M. Pei’s pyramids outside the Louvre or Daniel Buren’s marauding columns, a roving cannibal army seemingly bent on prying open the royal palace and devouring the rotting innards of French classical civilization.) Fredric Jameson used to call this a “hysterical sublime,” a sort of aesthetic euphoria or rush which he identified as the defining property of curvaceous, seductive postmodern arts and architectures — Paine’s giant trunk fitting the bill as much as anything. This art flourishes by plastering fragments of California or New York out on a planetary scale: all the flash and motion of international commerce and digital media, of untold networks of financial and informational power. (Behind this polished surface lies the sordid picture of refugee caravans, structural unemployment, ethnic war, debt, ghettos, etc. This might account for part of the public’s well-deserved suspicion, as if they guessed somehow the brutality and class violence behind the art institution’s human mask.)

Which brings us to Roxy Paine’s artificial trees. I doubt on other grounds that Paine has anything new or philosophically meaningful to say about the violent subjugation of Nature or the triumph of technical engineering. My impression — and the tepid, shifting arguments from Paine’s apologists sustain it — is that Paine’s belated philosophical meditations are merely a formal residue, outmoded habits left over from an arthritic modernism with a foot in the grave. Which explains why no one clung to them very long; NAG curator Marc Mayer, in a moment of desperation, even tried to sell the public on Paine being “a very nice man,” as if art commissions somehow depended on the artist’s character.

But what motivates my rejection is a conviction that Ottawa’s built environment, in its relation to the area’s natural features, once offered a unique aesthetic experience more in line with the older “Kantian” sublime, in this case the juxtaposition of human and geological timescales. What often struck me, living in Ottawa, is the city centre’s weak centre of gravity against the backdrop of nature, the missing sense of permanence. Even the National-Capital-Commissionized Ottawa, even this Ottawa of architectural heterogeneity, ambassadorial pomp, and precision landscape surgery, retained, I think, this odd feeling, this charm — despite every effort, Gréber on, to “build a proper capital” and, more recently, to pattern the city to a familiar North American urban background noise. The shanties and the lumber camps have all gone and yet the whole place sometimes feels like a camp in the wilderness, a temporary lodging: Viewed against the Gatineau Hills, everything threatens to regress, to decay, to break down. As if what we fear above all is a return to our inglorious origins: the provincial backwater, the military camp marooned in a trackless wilderness somewhere between Montreal and Kingston. (A “return to the primitive” which the anarcho-punks visibly embrace as they prowl neon-bathed Rideau Street.)

If modernism, as cultural history tells us, was an artistic attempt to express the jarring contrast between the Old and the New — to come to terms with the New’s radical newness and liberating potential, which is largely lost to us today (where everything is both “new” and a product), Ottawa was once the ideal illustration: What is older than the Precambrian crags of the Canadian Shield brooding on the horizon, and what is less complete than the schoolyard “capital,” the parliament in the wilderness, the blip on a placid river leading nowhere?

The river. Nepean Point, precisely, offers a view to the far shore (ignoring Gatineau’s federal government complex high-rise condos); to the interior with its silent hills, the sentinels of an unimaginably ancient and vast Canadian Shield. Only here does one begin to feel the presence of the North American Continent, its weight and its illimitable expanse: And even the native-born feel like interlopers, like tenants. Ottawa might have been a Caspar David Friedrich sketch, an arena or testing ground between the pretensions of culture and its eternal adversary, Nature — an encounter of Man with More than Man, or better yet, the crumbling of the social in its collision with the Earth.

But Paine’s crooked metal pole will command one of the few remaining sites where residents and visitors could experience this sensation and, more simply, view the valley relatively unimpeded by modernity’s twin faces; the soaring glass and, at its base, all that scrap and decaying infrastructure. Here the “nationalist” objection to Paine’s work, which invited so many rehearsed sarcasms from newspaper columnists and other professional scoffers, surfaces again with renewed urgency and clarity: Hundred Foot Line stakes out civic ground and rewrites it into an alien script which is no longer Nepean, no longer Ottawa. It neutralizes, releases from all history and memory, as if by planting this metal stake, the curators hoped once and for all to dissolve into dust any bond with the past, to set up a private theatre or playground where the image-shopper (of which the “art lover” is simply the purest class) may linger in amusement before moving on to another forgettable pavilion in the global corporate art gallery.

photo by Evan Thornton

3 comments

The Hundred Foot Line seems like a perfectly fine statue with some artitistic value. The problem is the location. If it were to be installed on Lebreton Flats and integrated into the new development it might really add something to new the community. Nepean Point is already a beautiful spot and adding this statue will unnecessarily overcrowd the visual environment as well as needlessly distracting from the location’s historic and geographic qualities.

I can’t tell whether Mr. Velarde is for or against “Hundred Foot Line”. His writing is so steeped in the jargon and hyperbole that ruins most academic dialogue on art, that it is impossible to take whatever his opinion is seriously, never mind decide what his opinion is.

He writes: “these public art installations are likely the latest phase in Ottawa’s well-known spatial mutation…” Well, are they the latest phase or not? And “spatial mutation”? – puh-lease.

Then he posits that “The problem, as I see it, is simple.”

But he goes on to describe the problem is a way that is so far from simple that it beggars belief. He writes: “Controversy, even a miniaturized one, allowed the Gallery’s curatorial mandarins and strongmen to short-circuit debate by positioning themselves as the bearers of progress and enlightenment…” I think I am supposed to understand that the Gallery folks forced the sculpture on us, so I am getting the impression that Mr. Velarde doesn’t like the art, and neither does he like the Gallery folks.

By calling it a “dramatic coup d’état at Nepean Point”, I get the impression again, that he doesn’t like the sculpture foisted upon us.

Then he writes the almost incomprehensible, “I believe we are witnessing the spatial byproduct of a civic demolition project at work since roughly the late sixties, with the corporate art-products celebrating a new global system emerging from the compost heap of decomposing nations.” Parsing this does not quite defeat me. I believe it means that the new order of public art is as crappy as the old order, but I suppose I could be wrong.

Finally he writes, “But what motivates my rejection…” and so I think he is against the “Hundred Foot Line”.

If I had not read this kind of writing in years past, while getting my own (albeit undergraduate) art history degree, I might have thought this was a parody, mocking both the people who advocated for the sculpture and those who resisted it. If it IS a parody, Mr. Velarde has outdone himself and the joke is on me.

Not sure I am quite convinced by Daniel’s argument although I certainly sympathize with many of its elements. I think Dave makes the key point in much simpler terms. Whatever you think of Paine’s sculpture, Nepean point is simply not the right place for a new installation of that scale. Wouldn’t it be more fitting, and perhaps unwittingly validating of Daniel’s argument, if it were placed not at Nepean Point but somewhere in Nepean. “Official Ottawa” – in this case the art mandarins at the National Gallery – needs to spread the love. There are far too many landscapes in this city that are what I would call unconsidered: when conceived, no consideration goes into their visual or spatial relationship to the wider city and once built, no one really considers them. They are places constructed to pass through (suburban feeder roads) or naked functional destinations (go, shop, leave). Why not place the sculpture somewhere in the suburbs where it could draw out and make meaning of these ordinary landscapes we too often ignore? Why not make these places more considered? Instead of neutralizing history and memory of pre-settlement life, such a sculpture in Nepean would actually encourage us to engage with history and memory, albeit of a more recent and – in the case of that most North American landscape, the post-war suburb – more embarrassed kind.