In 1880, a railway bridge was constructed, linking Ottawa, Ontario to Hull (now Gatineau), Quebec. This bridge, known as the Prince of Wales Bridge, spans the Ottawa River just west of the centres of both cities. In 1927 the steel superstructure was re-constructed on existing 19th century masonry piers and abutments.

Until the arrival of the O-Train – Ottawa’s light rail line – in 2001, the Prince of Wales Bridge carried passengers and freight as part of the CP Rail system. The O-Train took over the rail corridor south of the Transitway and the bridge has remained idle since. The City of Ottawa purchased the bridge in 2005. Various plans for the bridge’s reuse have been floated – and sunk – including use as an extension of the O-Train, as a rapid bus transit corridor and as a multi-use, cycling/pedestrian pathway. The bridge is not currently included in the City of Ottawa Transportation Master Plan (2013 – 2031).

Following the rail corridor north is another historic train bridge, crossing the Gatineau River. This bridge, known as Pont Noir, is identical in construction to the Prince of Wales Bridge and was built at the same time. Pont Noir was converted in 2011 to a bus rapid transit (BRT) line, with a cantilevered multi-use pathway.

Pont Noir offers a glimpse of what adapting the Prince of Wales Bridge to a new use could involve. Adapting the bridge for use as a BRT line or an extension of the O-Train would require the removal of the rails and the installation of lighting fixtures, signals and cables. The BRT, O-Train and even multi-use pathway options would all require major structural and seismic upgrades to the historic bridge.

The biggest change any future adaptation would bring to the Prince of Wales Bridge is that it would become a dedicated thoroughfare, while currently, it is largely a destination: despite No Trespassing signs, the bridge is heavily used by residents of both Ottawa and Gatineau as an unofficial public space.

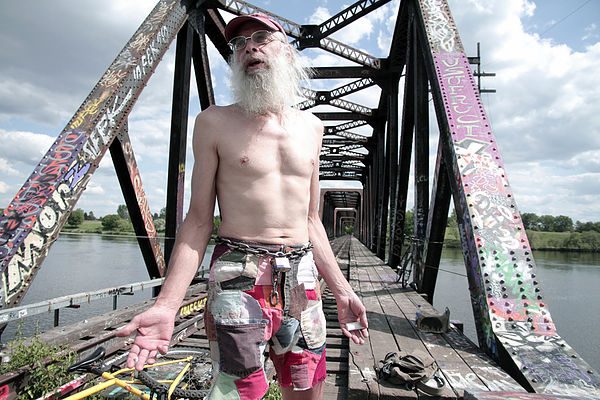

Because of its unofficial status, activities on the bridge are largely un-policed. You can run your dog off his leash. You can drink alcohol. You can paint on any surface you see fit. You can climb things and jump from them into water. In the National Capital Region, where space is strictly managed by both the City and the NCC , the bridge is a linear park free from regulation.

Despite all this, its largely an orderly and even a safe place. Two consecutive robberies in the summer of 2015 received media attention, but considering the popularity of the bridge day and night, those incidents were an exception to the norm. The fairly continuous presence of strangers may deter such crime as eyes are generally “on the street.”

Nothing honours a heritage structure more than to put it to use. Adaptive reuse also ensures continued upkeep and thereby longevity. But any official use the Prince of Wales Bridge is eventually accommodated to, even the relatively lightweight conversion to a multi-use pathway, will change the flavour of the public life it currently supports, and likely cleanse it of a large part of its charm.

The bridge is a decidely un-Ottawan place: its unofficial, weird and a little sketchy. A friend of mine described experiencing the bridge as “whatever the opposite of a reality check is”. Just down the tracks a barefoot young woman draws you in, singing folk favourites on her flower painted guitar.

On any given summer day, a group can be found around a diving board nailed into the timbers that form the bridge’s walkway. A rope is tied to the steel construction above and they swing out, dropping into the steady current of the Ottawa River. The board and rope were installed in 2013 by a Québecois, part-time wrestler known as “The Viking”.

As a peripheral space, the bridge attracts young people.

Just north of the Prince of Wales, another old track crosses over the rail corridor. For this group of twelve and thirteen year olds, its a favoured place to pass an idle summer day.

“Used to still be trains here when I came in the late 90s” John tells me. He’s been using the bridge since he settled in Ottawa, his years train hopping naturally leading him to the site.

At some point, John, a poet, artist and micropublisher, painted one of the bridge’s steel beams blue to create the effect of it disappearing against the sky. He’s been maintaining it ever since, touching it up every time graffiti spoils the illusion – sometimes every couple of days.

“Oh, it’s an educational experience coming down here” John tells me in reference to the unusual things one can encounter on any given day or night on the bridge. But the bridge also supports more conventional public use with joggers frequently passing through, dog walkers and the occasional family.

My friend suggested that the experience of the bridge is “whatever the opposite of a reality check is.” For others, the bridge, with its idyllic views and spontaneous social interactions, with the liberties it affords, are a reality check after a day of work in the National Capital Region.

The Prince of Wales “Park” is undefined, incomplete. An ongoing experiment. Participation in that experiment is a creative act, redefining and subverting the private space of the bridge with “public” use. By jogging. By installing a diving board. There is a feeling that anything could happen here. For the moment at least.

—

Text and photographs by Adrian Phillips