By Andrew Millward, Ph.D.

Director of Ryerson University’s Urban Forest Research & Ecological Disturbance (UFRED) Group

In this special article to Spacing Toronto, geography professor Andrew Millward describes the fatal impact our exceptionally dry summer has had on sugar maple trees in Allan Gardens. But it’s not the lack of rainfall that’s having a direct affect on the trees; it’s the park’s growing population of thirsty squirrels.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Torontonians will agree that this was a dry summer. But how dry?

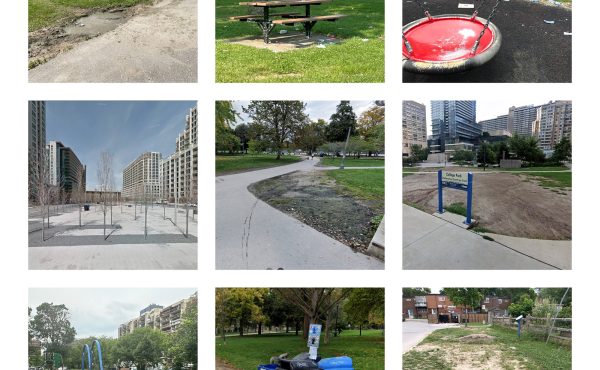

Acknowledging the obvious irony, my research group has been collecting data in Allan Gardens over the past year. Our goal is to quantify the potential of urban forests to attenuate storm water runoff. We operate a weather station in the park and have collected data that shows June and July received only one quarter of the rainfall downtown Toronto should expect (in comparison to the long-term average reported by Environment Canada). More alarming than this are the data for August. During this month, we found that Allan Gardens only received 7.6mm of rain, which is one tenth of the average. The repercussions of this are clear to most of us in the form of brown grass and wilting trees. What many of us tend to overlook, however, is the impact that this might have on our urban wildlife. This year, that oversight is not possible in Allan Gardens.

One of Toronto’s oldest parks, Allan Gardens is named after George William Allan, who was the philanthropist visionary who made it possible. It was officially named in 1901, but has been a city property since 1888. The park is best known for its botanical conservatory with a beautiful representation of flora. Enclosed by Jarvis, Gerrard, Sherborne, and Carlton streets, this 11 acre downtown oasis has more than 250 trees.

While providing respite for many who live and work in its proximity, the park is also home to a squirrel population that exists in relative isolation from surrounding neighbourhoods. The Eastern Grey Squirrel (of which the commonly seen black squirrel is a melanistic member) has a home range that rarely exceeds two acres. The four busy streets that delineate the park, coupled with few overhead wires serving as safe transit routes, reinforce these squirrels’ geographic isolation.

Food is of little concern to this squirrel population as the park has several large walnut trees as well as a steady supply of handouts from visiting humans. However, this summer, an unfortunate set of circumstances has come together to create a situation where water for “park-locked” wildlife is a very scarce resource. The City of Toronto has elected to not run any water in the park (including drinking fountains and the ornamental fountain on the parks western side). Further, there has been no irrigation in the park except for several small decorative flower beds.

In the spring Grey Squirrels, living in Eastern North America, have been observed to tap sugar maple trees for sap — but this has been reported by scientists as a food supplement when winter supplies are scant, not as a source of water. In early August of this summer, I began to observe an alarming phenomenon in Allan Gardens: squirrels were beginning to girdle sugar maples (remove the bark layer in a circular pattern). Just inside the bark layer is the tree’s cambium, which is its active living layer. The cambium is the part of the tree that transports sugars and water between the leaves and roots. Damage to the cambium arrests the flow of these, and will quickly result in the death of an affected tree limb.

Where this damage is extensive, the result will be fatal. While wildlife biologists have reported that the squirrel population is larger this year, due to the previous winter being warm, my research suggests that his phenomenon is not occurring in urban parks with adequate sources of water.

For more on this story, check out Dale Duncan’s article in today’s Globe and Mail.

3 comments

The Toronto Star’s fixer column reported on the dry fountain a couple of years ago. Apparently the city tried to fix it and briefly worked. However, there is some underground pipe that is leaking badly and it would be costly to fix it. So the fountain is likely to remain a dry pit for some time to come.

This is a fascinating study and set of findings. The limited range and the “tapping” habits of the squirrel are new to me. The sugar maples in New England’s urban parks and along the streets have not fared well, so it would be hard to observe squirrels tapping of them. However, some urban landscapes still support sugar maples and I wonder if this damage has been observed and if it is attributable to squirrels?

I continue to be impressed with Spacing’s attention to urban ecological issues in addition to its coverage of urban architecture, transportation, and politics.

There are many materially important things to be said about the value of the tree canopy in Toronto. I grew up in Parkdale and remember walking down Dunn Avenue in the fifties not yet ten years old taking such pleasure from the trees. I assume children remain capable of experiencing a pleasure like that. There were many elms and chestnuts. The branches of the trees met over the road. Through the heat of summer the street was a green nave. Sadly, here in west Toronto, the lush and healthy residential tree is becoming less common. These days it’s easy to recognize a tree someone is taking the time to water. So many mature trees and young trees look utterly parched. Some trees are so dry even the shade they cast is parched. A small but rewarding act to water a tree.

Joan Guenther