cross-posted from Steve Munro’s blog

Back in 1952, the TTC was about to open its first subway line and was contemplating the future of the streetcar system. Options included rehabilitation of its Peter Witt car fleet as well as the acquisition of more PCC cars.

By that time, new PCCs would be expensive as the market for them had more or less disappeared thanks to the onslaught of bus conversions in North America. However, many used fleets, some quite new, were on the market and Toronto was quick to snap them up.

A fascinating report to the transit commission dated June 3, 1952, was written by W.E.P. Duncan, Operations Manager, and it recommends among other things the acquisition of used streetcars from Cleveland and Birmingham.

This report is also interesting for what it tells us of demands on various major routes and the number of streetcars assigned to each line. The Bloor route, carrying 9,000 per peak hour/direction, would require 174 cars. Today’s network requires 192 cars in total, of which 38 are ALRVs. Demands have changed quite a lot.

The report includes strong language about the retention of streetcars, not a common approach in the 50’s.

There is obvious justification for the abandonment of streetcars in smaller communities but the policy of the abandonment of the use of this form of transportation in the larger communities is decidedly open to question. In fact it is hardly too much to say that the results which have occurred in a good many of these larger cities leaves open to serious question the wisdom of the decisions made.

It may be not wholly accurate to attribute the transit situation in most large American cities to the abandonment of the streetcars. Nevertheless the position in which these utilities have now found themselves is a far from happy one. Fares have steadily and substantially increased, the quality of the service given, on the whole, has not been maintained, and the fare increases have not brought a satisfactory financial result. Short-haul riding, which is the lifeblood of practically all transit properties, has dropped to a minimum and the Companies are left with the unprofitable long hauls. Deterioration of service has also lessened the public demand for public passenger transportation. The result is that the gross revenues of the properties considered, if they have increased to any substantial degree, have not increased anything like the ratio of the fare increases, and in most cases have barely served to keep pace with the rising cost of labour and material. It is difficult to see any future for most large American properties unless public financial aid comes to their support.

These facts being as they are, Toronto should consider carefully whether policies which have brought these unfortunate results are policies which should be copied in this city. Unquestionably a large part of the responsibility for the plight in which these companies find themselves is due to the fact that the labour cost on small vehicles is too high to make service self-sustaining at practically any conceivable fare.

Why then did these properties adopt this policy? It is not unfair to suggest that this policy was adopted in large part by public pressure upon management exerted by the very articulate group of citizens who own and use motor cars and who claim street cars interfere with the movement of free-wheel vehicles and who assert that the modern generation has no use for vehicles operating on fixed tracks but insists on “riding on rubber”. If there is any truth in the above suggestion it is an extraordinary abdication of responsibility by those in charge of transit interests. They have tailored their service in accordance with the demands of their bitter competitors rather than in accordance with the needs of their patrons.

Two important points made here still apply today.

First, the importance of the short-haul rider. These are the cheapest to serve. In the flat-fare environment of the 50’s, they would also yield the greatest revenue per passenger and were most sensitive to quality of service. We know this today — people love the ability to jump on a vehicle for a short trip provided that they don’t have to wait very long for it. If they can walk faster, they do, but deeply resent the poor service.

Second, is the attitude that motorists should not be catered to as fellow users of the road. Transit should not adjust to accommodate them, but should address them as rivals. In today’s context, this churns up the “war on the car” rhetoric, and the days when transit could demand precedence are long gone. All the same, transit gives up too easily too often because politicians talk a good line about priority measures but go to great lengths to avoid hurting motorists.

The plan set out in the report set the stage for the eventual elimination of streetcars by 1980 on the assumption that the major routes would be replaced by at least one of the Bloor or Queen subways, even though the latter would be initially operated with streetcars. This leads directly to the suburban rapid transit plan of 1969, described in the previous article.

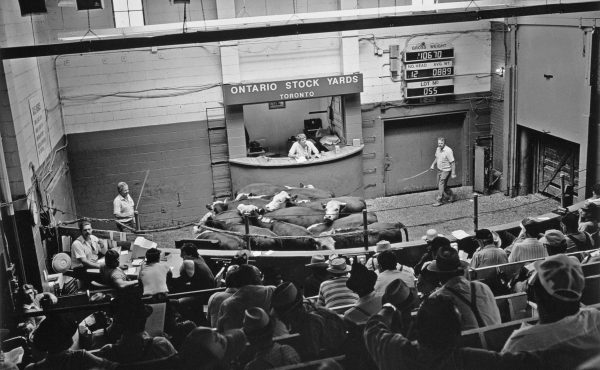

photo from Toronto Archives: Series 648, file 155, id 12

7 comments

“The previous article” mentioned above, is on my own website. It reviews a Globe and Mail piece from 1969 in which the TTC talks about building a network of suburban streetcar lines.

http://stevemunro.ca/?p=3129

Thanks for the link to the previous article, Steve, and for this interesting post above. I like short trips, and hope that the TTC will indeed implement the 2 hour transfer along with Presto to accommodate multiple errands in one outing.

I hope Steve Munro is not implying that the

photo is from 1952.

The photo shows a Pontiac dating from the

late ’50s. The distinctive grill design

dates from 1959.

No, Steve is not. I chose it (since I’m the art director) as it was the closest I could find to 1952 in the Toronto Archives.

If you go to the version of the article on my website, you will find links to Transit Toronto where there are photos of the second-hand cars the TTC did buy.

Fascinating – great to see a time when government policymakers were willing to think for themselves and stand against trends being adopted by other jurisdictions because of lobbying by interest groups.

wonderful posting! as a vancouver local, it makes me question why we ever gave up our streetcars. thank god at least we have trolleybuses…