This post is part of a series of articles exploring the Environmental Assessment process and how it’s shaping Toronto. The series focuses on four major developments currently at the EA stage.

This post is part of a series of articles exploring the Environmental Assessment process and how it’s shaping Toronto. The series focuses on four major developments currently at the EA stage.

Though you may not know much about the person sitting next to you on the streetcar, chances are you have at least one thing in common: you both want to get to where you’re going quickly. Whether we are heading towards Kennedy Station or a revitalized approach to urban transportation, we’re understandably impatient about arriving at our destination.

In the case of a better transit system, each of us is silently groaning, “are we there yet?” And why shouldn’t we? Changes to the TTC will alter our paths and patterns, economic possibilities, and environmental realities in a way that few other projects can.

Like a long ride with many transfers, the environmental assessment process is notoriously arduous — which is why the Ontario Government made the bold move in 2008 to streamline transit undertakings as a unique class of environmental assessments known as Transit Project Assessments.

In this edition of the EA series, I’ll be looking at the Transit Project Assessment process through the lens of the Scarborough-Malvern Light Rail Transit (SMLRT) project. This project, in various incarnations, has been a transit pipe dream since the 1980s. Bandied back and forth for several decades, it gained steam with the Transit City announcement in 2007 and again last year when Toronto’s 2015 Pan Am Games bid was accepted.

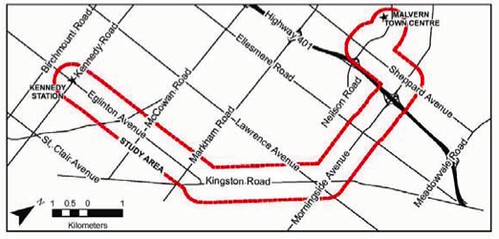

Broadly, the project seeks to improve transit access to northeast Scarborough, support local population and employment growth, accommodate future ridership, connect Scarborough Rapid Transit to the Sheppard Light Rail Transit line, and provide rapid transit access to Centennial College’s Morningside campus and University of Toronto’s Scarborough campus. The 10-kilometre route has committed funding of $1.4 billion, and is expected to will hopefully open in time for the Pan Am Games. (The image above is the planned route. For more information about the specifics of the route, please see the SMLRT Environmental Project Report Executive Summary [PDF].)

Under the guidelines of the streamlined transit project assessment, the SMLRT is exempt from the requirements of a regular EA. This means no terms of reference (ToR) document is produced. Recall that the ToR defines the scope of the assessment and involves a fair portion of the public consultation (see our EA Primer for more details). As Steve Munro rightly noted a in a comment on a previous installment of this series, there’s an expectation that “a lot of the legwork of public consultation and a good chunk of preliminary design will happen before the [transit project assessment] formally gets underway.”

What the streamlined transit assessments sacrifice in content, they make up for in time: Transit EAs have six months to cross the finish line. Unlike other EAs, the Transit Assessment begins with a chosen transit project. In other words, proponents do not have to justify the need for the project or identify alternative solutions. Instead, the assessment requires proponents to describe the project and its design, consult with appropriate stakeholders, evaluate potential impacts, and offer proposed measures for mitigating these impacts.

Munro has concerns about transparency and meaningful opportunities for public comment. “[The Transit approval process was] badly perverted in the old way,” he says. “The new way relies on the good will of the proponent to undertake proper public consultation prior to the process itself. By the time the project receives consultation, detail and design decisions have already been made.” Streamlining eliminates some key opportunities to present ideas, collect feedback, adapt plans, and gain public trust.

Some argue that, when it comes to transit, this streamlining is justified. The Ministry of the Environment reasons that “a shorter process for these environmentally beneficial projects will help get people out of their cars and onto public transit. This is good news for Ontarian’s health and the health of the environment.” The SMLRT’s Environmental Project Report estimates that particulate pollutants will decrease by 25 percent, gaseous pollutants by two percent and carbon dioxide by 1.2 kilotonnes per year within the study area as a result of the LRT.

Positive impacts of the SMLRT extend beyond atmospheric concentrations and into community benefits. There is broad consensus in the planning community about the economic benefits of LRT. According a recent Region of Waterloo study, “[r]ail transit has a demonstrable influence on land values and locational decisions and is recognized as a planning tool that can support and encourage the development of more sustainable land use patterns. LRT has been shown to influence land development in part because, being tied to tracks, it is both distinct and perceived to be permanent.” With 45 percent of Malvern residents over age 15 qualifying as low-income earners, the sooner these benefits reach northeast Scarborough, the better.

But Ontario’s Environmental Commissioner, Gord Miller, gives the streamlined process an amber light. Citing the public uproar around the use of diesel cars on the Union-Pearson rail link, the Commissioner worries that “the streamlined transit EA doesn’t allow for the consideration of alternatives. Had the Union-Pearson EA been completed in a more classical sense, we might have ended up in the same place without all of the irate people. We ended up with the best alternative but not in the analytical, progressive, consultative way that EAs are supposed to proceed. We ended up there through conflict, which the EA is supposed to avoid.”

While transit comes with many obvious environmental benefits, Gord Miller reminds us that “some elements of these projects can be highly problematic and thus should have a process that incorporates considerations of need and alternatives.” He says it’s a matter of scope and magnitude — while the SMLRT has been relatively smooth sailing, not all transit projects are uniformly beneficial.

The SMLRT has justifiably broad public approval; there are measurable net benefits to reducing vehicular traffic, facilitating economic development, and linking a Toronto neighbourhood to the wider city. But transit projects as a whole deserve transparent analysis and the scrutiny of an informed public empowered with meaningful opportunities to shape final outcomes. Next time you find yourself nose-to-nose with an impatient TTC stranger, consider asking him or her whether it’s worthwhile to take some extra time to get where we are going.

With thanks to Steve Munro and Gord Miller

6 comments

“We ended up with the best alternative”? I’m confused by this statement. Using diesel on the Union-Pearson rail link cannot possibly be considered “the best alternative” when by every measure, this kind of project should be electric. The fictional notion that the Georgetown GO expansion will use as yet non-existent clean diesel is simply green washing so how can that be “the best alternative”? Over 400 diesel trains per day spewing toxic air pollution through residential neighbourhoods, past schools and playgrounds; that’s certainly not “the best alternative”. So what am I missing?

The EA process was certainly problematic but the suggestion that the process alone is the problem misses the point. The problem is the conclusion to proceed with diesel; we’ll have long forgotten about the problematic EA process while we’re living with its toxic conclusion.

I live in the south-western tail of this study area, and anything that brings more transit to the neighbourhood is good.

In San Francisco, some NIMBY’s tried to use their version of an Environmental Assessment against bicycle paths. After a great expense, it was reluctantly done, but the result was a delay.

“What the streamlined transit assessments sacrifice in content, they make up for in time:”

That’s certainly a view through rose coloured glasses. The work is done before the TPA starts, so the only impact of the six month time limit is that it pushes the start date later – to six months before the intended conclusion rather than at the actual start.

The article says “The 10-kilometre route has committed funding of $1.4 billion, and is expected to open in time for the Pan Am Games.”

There’s been no committment of funding for this line. Do you guys just make this stuff up?

Both halves of the statement about funding and opening are wrong.

There is no funding. $1.4b sounds like the money for the Scarborough RT project, not the Scarborough Malvern project.

Also, some folks (notably the Mayor) are pushing for this line to be open in time for the games. Now that the SRT is going to be LRT it would be possible for the two-week period of the games to run direct service to UTSC from both Kennedy and Don Mills Stations provided that the 2km section of the SMLRT is built from Sheppard south to the campus.

For reasons that defy understanding, this option, though oft suggested, is being ignored.