By popular demand, Spacing presents a print-out, fold-up, all-purpose guide to Environmental Assessments in Ontario.

By popular demand, Spacing presents a print-out, fold-up, all-purpose guide to Environmental Assessments in Ontario.

What is an Environmental Assessment?

An Environmental Assessment (EA) is a planning tool used to identify the potential environmental impacts of proposed development and incorporate considerations of those impacts into decisions about our future. The process is governed by Ontario’s Environmental Assessment Act, 1990.

What kinds of projects require an EA?

It’s tough to say for sure. All public and some private plans, programs, and projects with implications for the public good are required to complete an assessment. Typically, roads, landfills, water and sewer undertakings, power generation and transmission, forestry, and transit projects complete an EA. That being said, the Minister of the Environment can exempt projects from the EA process and only one Provincial plan, Ontario’s Hydro Demand Supply Plan, has ever had an EA Hearing.

Who is involved in an EA?

The following parties play a role in the process:

The proponent — The proponent is the project’s champion. They initiate the development proposal and answer the requests and questions of other participating parties.

Ontario Ministry of the Environment (MOE): Environmental Assessment and Approvals Branch — This is the one-stop shop for regulatory environmental approvals in Ontario. They oversee the implementation of the Environmental Assessment Act.

Provincial ministries and agencies — Various Provincial ministries and agencies are involved in reviewing the project and assessment as needed.

Federal ministries and agencies — Federal ministries and agencies are involved in reviewing the project and assessment when projects require Federal approvals, permits, licenses, or funding.

Ontario Minister of the Environment — The Provincial environment minister, currently John Gerretsen, can exempt projects from the EA process. The minister also releases assessments for public comment, determines whether a hearing is necessary, and accepts or rescinds the final decision.

Public — The public has a few chances to engage in the EA process. Notice and opportunities for public comment are given when the proponent submits the Terms of Reference (more on that later), when the EA is submitted, and if the assessment proceeds to a hearing.

Ontario Cabinet — Cabinet must approve the environment minister’s decision to accept the EA.

Environmental Review Tribunal — The Tribunal oversees EAs if and when they proceed to the hearing stage. They offer a decision on the basis of testimony at the hearing.

How does it work?

Stage 1: Project Proposal

1. The proponent proposes a development project.

2. In consultation with the MOE’s Environmental Assessment Branch, the proponent confirms whether the project requires an EA and, if so, what type. The MOE has established the following three EA templates to speed up the approval process for similar projects.

• Individual EAs are for “large, complex projects with the potential for significant impacts on the environment, such as major landfills.” According to the MOE, Individual EAs comprise less than five per cent of all applications.

• Class EAs are for specific types of projects classified according to similarities in their potential environmental impacts, such as municipal roads, water and sewer, forest management, highways, and GO Transit. Class proponents must prove that their project merits such an assessment on the basis of the similarity between the potential impacts of their project and those of other projects evaluated in this manner. The Class EA is the predominant form of assessment and some have suggested that this template has sacrificed oversight in favour of faster results.

• Electricity generation and transmission EAs vary depending on potential environmental impacts and the nature of the project. Proponents will either follow an individual EA or have no EA requirement.

3. The proponent provides initial opportunities for community consultation with regards to the proposed project.

Stage 2: Terms of Reference

4. The proponent completes and files a Terms of Reference (ToR) document. This report defines the scope of the EA that will follow. According to the Environmental Assessment Act, the ToR must demonstrate that the EA will be prepared in accordance with the Provincial requirements and the conditions particular to the type of project proposed. The ToR also describes initial public consultations and their outcomes.

5. The ToR is made available to the public for review and comment.

6. The Minister of the Environment approves, amends, or rejects the Terms of Reference.

Stage 3: Environmental Assessment

7. The Proponent prepares the EA, which must include: a description of the project as well as its purpose and rationale; alternatives to the project and to the proposed methods of its execution; a description of the environment that will or could be affected and the nature of those effects; actions necessary to prevent or mitigate those effects; an evaluation of the advantages and disadvantages to the environment of the undertaking and alternative options; a description of the consultations and their outcomes; and any other items as identified in the ToR.

For more information on the EA process, please check out the Environmental Commissioner of Ontario’s 2007-2008 Annual Report.

(With thanks to the Environmental Commissioner of Ontario and the MOE.)

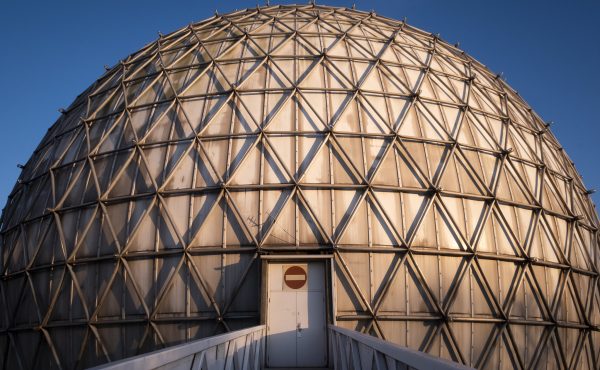

Photo of the St. Clair streetcar right-of-way construction by Stephen Parker

9 comments

Hilary:

You need to clarify that many transit projects are no longer subject to an EA as described above, but to a separate transit project assessment. Notable by its absence in this is the Terms of Reference phase, and there are strict timelines on what’s left.

The expectation is that a lot of the legwork of doing public consultation and a good chunk of preliminary design will happen before the TPA formally gets underway. However, I don’t think anything prevents a proponent from bulling ahead on a quickie TPA beyond whatever political opposition might (or might not) be stirred up.

this post looks like a Civics project i once had to do in Grade 10

Did you pass or fail, a?

This article, unfortunately, doesn’t provide enough detail to help those who are unfamiliar with the processes.

The Ontario Waste Manage Corporation was subject to hearings back in the 1980s – but they were never completed.. OWMC was a Provincial Crown Corporation that was charged with finding a disposal site for hazardous waste. There have been relatively few hearings for EAs when compared to the thousands that have gone through. By suggesting incorrectly that the Province has had only one hearing suggest they were treating most municipalities differently. For example, the City of Toronto has never had a hearing on its hundreds of EAs per year.

Although the Class EA is part of the broader EA process, nesting it inside the Individual EA process as you have done above only confuses. Either you carry out a Class EA or you carry out an Individual EA. You don’t do one as part of the other. A proponent can elect to upgrade from a Class EA to Individual – which Metro did when they upgraded the Ashbridges Bay Treatment Plant from a Class EA to Individual. It would be useful to explain the different levels of Class EA in more detail. For example, the Municipal CLass EA which covers transit, roads, water and sewage has A,B, C levels – A being automatic approval and C being quite comprehensive – an almost individual EA, but not quite. They do differ from Class EA process to Class EA process.

Finally, it’s not that confusing to determine what is eligible for an EA. Just about any municipal project that’s waste management (except recycling/diversion facilities), roads, water, sewage and transit. A few others fall into the EA process – and most private sector organizations don’t have to do one. A good number have volunteered to do so.

EAs are dare I write it – full of EArcane details, and at times it feels that the public isn’t of use, that the agenda is set, and the options are either not thought through, or simply limited.

Once upon a time there was an intervenor funding for citizens too – it is something that should be reviewed, and perhaps that could be begun here.

If you ever wish to move beyond theoretical to the more practical, and to the very local ie. in the core of TO, consider looking at the EAvasion of the Bloor St. Transformation work – a $25M project is lowballed by the CIty into a class A rubberstamp somehow – so no real public consultation, and a private paving party (as merchants are paying 4/5 of the luxe cost) is missing public priorities like safe biking, having bike parking, or conservation of materials in sound sidewalks.

In the end, it may be enough to kinda sink Yorkvile – or one can sorta hope.

Meanwhile, they’ve started trashing further the road and it’s become more of a nightmare to bike on, though I was still able to pass most cars.

You also might want to look at how long these EAs can last without any staledating eg. FSE, and its companion the WWWLRT, which is actually a solid piece of work, with some good conclusions and options for effective east-west transit…

This seems so simple – why do some EAs take many years to complete despite rather obvious outcomes? If possible, could you clarify the provincial/federal jurisdictions. Are federally regulated areas also required to do EAs?

One criticism I’d heard was that the EA process requires clearly defined design and once completed it does not allow room for adaptation. Could you comment?

A worthwhile series – please continue and expand on this.

Some EAs take much longer than others (this is the simple answe) a) if there is serious public opposition, or b) if the content of the study is complex or c) a combination of both. Another factor is the ability of the project team to respond quickly to public concerns. Some teams are more nimble than others.

It is possible to change an EA process,, but that’s time consuming. Expanding or contracting portions of the EA plan (within reason) is how most adapt to public concerns. Under Class EA, depending on the schedule, there are relatively few required points of public contact from a public perspective. Expanding this beyond the minimum is one way to adapt the process and why some EAs run so long.

Hilary:

A few major omissions in your article: Class EAs do not need a Terms of Reference – this is only for Individual EAs. Also, Class EAs do not assess planning alternatives (“Alternatives to the Undertaking”), whereas Individual EAs do. Although you mentioned GO and highways, you did not mention that GO and the MTO follow their own Class EA process which is prescribed in their own Class EA manuals. The ORC is another provincial agency that has its own Class EA process. Roads and waste water/sewers fall under the Municipal Class EA process.

It would been more informative if you actually identified all of the categories prescribed under the Municipal Class EA, i.e. Schedule A, Schedule B, and Schedule C, and described their differences.

Hilary:

Just another note, in addition to the Transit Project Assessment which is a separate EA process, transit projects can also follow the Municipal Class EA process if the proponent chooses to.