This post is part of a series of articles exploring the Environmental Assessment process and how it’s shaping Toronto. The series focuses on four major developments currently at the EA stage.

This post is part of a series of articles exploring the Environmental Assessment process and how it’s shaping Toronto. The series focuses on four major developments currently at the EA stage.

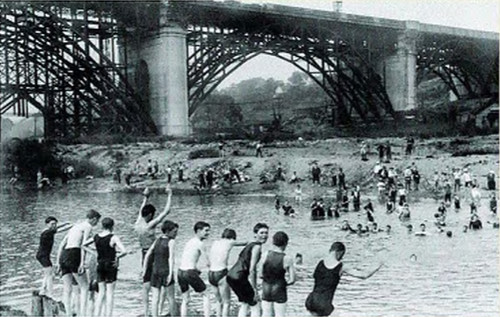

Photos like this one seem like they were taken a lifetime ago. Hilarious bathing costumes aside, the idea of swimming in the Don River is about as foreign an experience as I can think of. I know the Don as a sidekick to the DVP and as a treasure trove of beer cans and shopping carts. Though I grew up close to it, I have never dipped a toe into it or taken a drink straight from the river.

Can you blame me? From kindergarten on up, we were taught that the Don was dirty. And my teachers weren’t wrong. The Don River does not meet Provincial water quality objectives and has the dubious distinction of making the International Joint Commission’s list of 43 “areas of concern” in the Great Lakes Basin. It is one of the city’s most degraded ecosystems.

As it turns out, you can blame me. Along with nearly half of Toronto’s residents who make up the Don River sewershed, I’ve had a hand in the Don’s current condition. The sewers which combine and carry away stormwater and sanitary waste bound for the Ashbridges Bay treatment plant routinely overflow, loading up the Don with bacteria and nutrient pollution.

As it stands, our wastewater infrastructure progressively degrades this ecosystem and the water we drink. We’ve created a system which undermines itself and the value that we place on clean drinking water and a healthy environment.

With the release of the City’s Wet Weather Flow Master Plan in 2003 and the subsequent Don River and Central Waterfront Project, the City of Toronto is trying to stem the tide, initiating the process of restoring e.colic to bucolic.

The City proposes to address the need for additional sewer capacity to meet forecasted demands as the city grows while better managing the “wet weather” flows which wreak havoc on the Don. This requires changes at the source (lessening the load by disconnecting downspouts, planting trees, and promoting green roofs), during conveyance (allowing percolation of wastewater into soil for natural filtration where appropriate, separating sanitary from storm sewers, upgrading large trunk sewers) and at the end of the pipe (improving the quality of the water emerging from the Don’s 51 combined sewer outflows).

This project is subject to a Municipal Class EA.

This class of projects includes municipal “maintenance and operational activities, reconstruction and modification of existing roads and traffic facilities, the construction of new roads, reconstruction and modification of existing sewage, stormwater management and water facilities, the construction of new sewage and water facilities and the construction of stormwater management and related erosion, flood and water quality control facilities.” It will also be subject to a Federal Environmental Assessment on account of the potential implications of the project for navigable waters, fisheries and federal project funding.

Like other EAs, the municipal process mandates public consultation, the consideration of alternatives, identification of the potential environmental impacts of the project and the recognition of the advantages and disadvantages of the candidate solutions. Following public consultation and planning stages in 2008-2009, the City will release a preferred design document and environmental study report for public viewing this year.

City literature suggests that this project will “make the largest contribution to water quality improvement and habitat creation in the Don River in our lifetime.” This is a big step and one that future generations will thank us for (particularly if it allows them the chance to swim beneath the Prince Edward Viaduct).

The Don River project is exactly the kind of development decisions that the EA should be promoting: finding opportunities within decaying infrastructure to lessen the burden on our natural systems and improve quality of life. It does this by starting from a place of genuine need, a problem rather than a new project. The result is net ecological benefits rather than mere mitigation of new environmental ills: a standard that other assessments should be held to.

Photo courtesy of Toronto Archives

6 comments

I’m glad you’ve written about this. It’s not glamarous, but it is very important. This will be a major step forward for Toronto.

Parking lots, roads, rooftops, and driveways direct rainwater into the storm sewers instead of being left in puddles in fields to be adsorbed into the ground. This means each time it rains, the water is quickly directed into the rivers and streams. The water level rises rises very quickly, carrying oils, dirt, animal waste, and rubbish left around into the waterways. If the water was left in the fields, it would be percolate into the ground and be filtered by the ground. Slowly, the water in the ground would seep out into the valleys as springs and raise the water levels during the dry periods. The water, since it would have been filtered by the ground, would also be cleaner.

EAs is a crucial stage to redeveloping brownfield sites – look around us, we have polluted our own backyards and other peoples backyards. I hope this project and many alike show the importance of EAs as it allows efficient, cost appropriate, and suitable strategies to be conducted. Abandoned brownfield sites reveal the vulnerable characteristics of our city and with positive outlook for our future, these sites open window of opportunities to amazing phytoremediation/ bioremediation projects. Let’s bring the healthy ecosystems back into a city we call home!

Last summer I was bicycling along the Don and saw a huge mass bobbing up and down against the current. It turned out to be a snapping turtle. Unbelievable what stressors nature can endure. Imagine when we clean it back up again.

bravo!

Thanks Hilary

I’ve heard the Don big pipe solution called many things but you’ve eloquently raised it to the status of an iconic saving grace. Certainly source protection is the best solution, but Toronto has rested on its downspout disconnection laurels for decades now while other cities have zoomed into the low impact development capacity building present. The Don trunk tunnel, as the project will actually be, is designed, yes to divert CSOs from the Don, but at the expense of surcharging the Ahsbridges Treatment plant and as usual, reducing the funding and emphasis that ought to be placed on lot level solutions, permeability coefficient based bylaws for planning approvals, and even a stormwater utility structure to fund not the pipes and tanks that Toronto has relied upon since the WWFMMP was completed, but true lot level solutions as you spoke of – rain harvesting, urban forestry, pollution prevention, conservation and public engagement. In effect, the 5 Things you can Do For the Don, a RiverSides program that having won the Great Lakes Governore’s award for public outreach and education on contaminated stormwater, was promptly marginalized by the City of Toronto.

The central waterfront plan, the Don trunk sewer tunnel and the larger wet weather master plan process is alas, old pipes and pumps masquerading as advanced policy. Sad to say but Toronto slips further and further behind with every passing wet weather project that comes out of that plan.