It shouldn’t come as much of a surprise that Toronto’s street food scene falls very short of our city’s reputation of being ethnically, and culinarily, diverse. Despite the success of food festivals like Taste of the Danforth, the city’s day-to-day street food culture is being mired down by red tape, both real and imaginary, while other North American cities are recognizing the growing culture of street food.

An increasing interest in the recently popularized food truck industry has strengthened efforts to bring back street food. There were two obvious issues stopping gourmet food trucks from hitting the streets of Toronto – stringent health and safety regulations for mobile food units and a moratorium that was placed on issuing curbside permits within the three main wards (20, 27 and 28) of the downtown area. Previous misconceived notions that food truck establishments posed a greater risk for health and safety regulations have been reevaluated by Toronto Public Health. As such, menus for food trucks operating with full kitchens are now able to offer a much wider range of food options, much like a restaurant on wheels. Toronto Food Safety manager Jim Chan explains that the lift on menu restrictions for food trucks comes in light of a reality that health and safety depends on the operator, and not the type of establishment. – Take for example the temporary closing last October of upscale grocery store Pusateri’s after a rat and roach infestation.

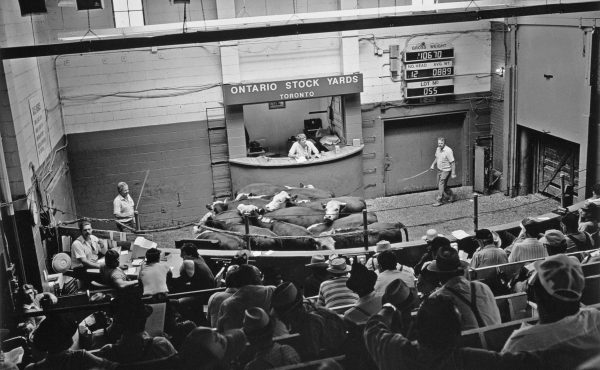

So Food Trucks now have the ability to offer a wider variety of food, great! So where are the Toronto truck vendors? They are becoming more visible at events around the city, but where are the wonderful community gatherings of gourmet trucks and vendors like those in Vancouver, or Portland? The truth is they are anxiously awaiting email replies from MLS which seem to be lost in the ethos, or playing telephone tag with contacts offered by MLS representatives who know little more than that there are simply no licenses available. This brings us to the second obvious reason for the lack of street food vendors – the moratorium which was placed on issuing permits for curbside vending ten years ago. The reason for this moratorium is what is least obvious, yet most commanding in keeping vendors away. Sadly, it is a misguided prejudice toward independent and family-run vending establishments led to a very powerful attempt for their extermination. This came evident during the city’s anticipated Bloor-Yorkville beautification project, which has recently been completed. The city wanted to clear the new granite boulevards of what was considered as untidy or undesired vendors, many of which are part of minority groups.

What the city councilors fail to see as they zoom by vendors in their automobiles is the community aspect of these small-scale businesses. Within the half hour that I stood by Marianne Moroney’s hot dog stand, I couldn’t help but notice a beautiful relationship between Moroney and the community, including children from nearby schools and those working in the surrounding hospitals along University Avenue. Parents would let their children run way ahead to greet Moroney on their daily route home. This micro-community aspect is unlike anything that can take place through the walls of a closed brick-and-mortar establishment, for which most passerby are just that – passerby with little engagement to their surroundings. (Editor’s note: For more on Moroney, see the Placemaker’s column in Spacing’s Fall 2010 issue)

The plan to abolish independent street vending continued with the introduction of the A La Carte program in 2009. The program was an attempt to provide diverse street food under a strictly controlled process (for which identical, very expensive, and often-problematic vending carts would have to be purchased through the city), which left little to no room for profit and actually led most of the vendors into personal financial crises. Existing hot dog vendors who initially wanted to join the program were not allowed to make minimal changes to their establishments or menus, and would have had to give up their current locations and carts for inferior ones. As a result, many experienced vendors did not partake in the program, and those who did were forced to invest in specified components supplied by the city for their carts, including malfunctioning fridges which cost several thousand dollars. Moreover, the program was to operate under a new and different Act (Chapter 738) from hot dog vendors (who operate under chapter 315). This would allow the city to turn down renewals and applications from hot dog vendors who were not under the new act, despite stating in Article II – Healthier Food Endorsements that “persons currently holding a valid original permit may apply under this chapter for an endorsement to permit the sale of healthier foods from the permitted cart on the terms and conditions as set out in the original permit, except as modified by this chapter.” When Moroney successfully applied for a change in her menu, she excitedly wrote applications for many other vendors, all of which were turned down by the city. Moroney remains the sole downtown street vendor whose request for a change in menu options was granted. Moroney openly expresses that this is due to racial prejudices that are held against the majority of food vendors in the city.

In ten years, the city’s efforts to abolish street vending succeeded in bringing approximately 300 permits to 128. Today, a growing demand and interest in food trucks by post-recession populations and positive media representation led to greater pressure on the city to lift the moratorium. The pressure is definitely on and negotiations are set to continue this month, with a probable draft to be submitted to city council by March of 2012. Moroney explains that ideally, this would take Toronto back to its pre-moratorium vending figures. In addition, city zoning for public and private parking lots would have to be revisited in order to support different types of food vendors.

Once this happens, the challenge will be to create a sustainable program that will benefit the community, vendors, and nearby brick-and-mortar establishments alike. In this sense, a balance would have to be found between mobile trucks and fixed carts. While mobile trucks are easily able to service various areas of high demand (ie. outside sporting venues on event days), carts are able to service a community without exhausting diesel fumes. Suresh Doss, organizer of Food Truck Eats explains that we are lucky to have the opportunity to look at success and failure stories of other cities in Canada, and throughout the US since each state has a very different approach to their street food scene. For his three day event which took place in the Distillery District this year, Doss did this by incorporating food trucks, vendors, and restaurants. The result was a very successful increase in profits from all parties, and no negative feedback. This comes a long way from the Toronto A La Carte dictatorship, which was destined to land flat on its face before the shrimp even hit the grill.

Like in the Distillery District this summer, Portland has been celebrating its street food for years, thanks to a laissez-faire approach by the government and available space on privately owned lots. With few zoning restrictions and much opportunity, developers began designing unused properties with all the amenities for a food cart. Brett Burmeister of Food Carts Portland explains that “The one thing that’s different with Portland is that we didn’t design it. It created itself, just through an interpretation of the laws, but we don’t have the laws that were created in other cities.” The result was an organically grown system of food pods where vendors of all different types gather to enjoy food culture. From this even stemmed a bicycle delivery system and in the case of Vancouver, much safer streets and vibrant communities. Let us learn from and strive for this in Toronto 2012.

3 comments

Great post which covered a lot of points. While I might agree that a combination of race & power is the biggest issue, there is also the issue of fair competition. Fixed retail pays more in property taxes, mortgages or leasing fees than vendors pay in licensing fees. This should allow them to sell (very limited) food items more cheaply. I imagine a lot of vendors would agree to pay more for licensing, depending on location, in order to get space and offer a wider selection of foods.

Much of today’s retail, especially with institutions like universities and hospitals is in an internal mall format. Vendors would put life back on these streets.They also would help livelier streets as well.

I just came back from a day trip to Montreal for business. I had lunch with two colleagues there, and they told me that the necessary highlights, for them, of a trip to Toronto, was visiting St. Lawrence Market and getting a hot dog from a street vendor. Even in the dead of winter, they and their children must get a hot dog to eat if they are in Toronto.

Which I found strange, but flattering: Let’s consider that for all the grief we give ourselves over street food, the one we do allow, we apparently do exceptionally well.

R.

@Roger: Putting life back on the streets is key, as well as giving vendors (often new immigrants) who are unable to afford the investment of a closed (brick-and-mortar) establishment a chance to make a decent living doing something they are passionate about. Lower costs aside, it is not without its difficulties, especially during the winter months. I do think that a better (or more organized) solution needs to be found as a mileu between the two types of establishments.

@Richard:Agreed. Street meat tastes great, especially in Toronto! My only concern would be to allow vendors to branch out in their suppliers, allow for competition and (as a result) possibly better quality food. From my understanding, all or most Toronto hot dogs come from the same, single supplier.