I’ve been a business reporter longer than I’ve covered politics, and I can say without fear of contradiction that the City of Toronto’s budget documents — which are squarely in the public eye as the annual spending fight commences — are the most impenetrable financial reports I’ve ever had the pleasure of decoding.

Each year about this time, they land with a (real or virtual) thud in the press gallery, the second floor of City Hall, and online, providing a textbook example of how some organizations use information to obscure, rather than enhance, understanding.

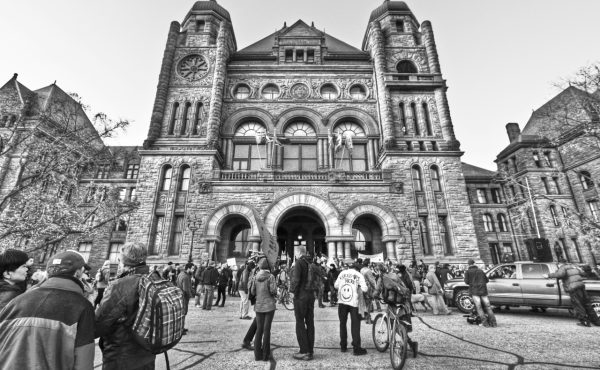

As council begins its annual budget consultations today, I’d argue that these voluminous, impenetrable doorstops, more than any other single factor, serve to prevent effective public engagement in the critical process of figuring out how the City should spend the funds entrusted to it by the residents of the city.

Over the years, 2012 being no exception, critics have bemoaned the lack of an effective budget consultation process. We talk endlessly about better online engagement (e.g. Naheed Nenshi), and approaches that are not designed to weed out all but the most determined or bloody-minded deputants. The participatory budget processes used by a few Latin American municipalities are cited as inclusive models to emulate, yet the comparisons to our own system are at best far-fetched.

Despite the hand-wringing, the City and Council makes no systematic attempt to present the information in an accessible format that allows residents to respond to the data, and, most importantly, understand it in a meaningful context. Instead, the city does its annual data dump, featuring reams of partially undigested numbers and perplexing calculations that smother careful consideration. The budget reports may be public documents, but they are most assuredly not public-spirited.

For the Toronto communications staffers who may be listening on the line, I should say here that I’m NOT advocating snazzier print and virtual PR materials, like the little charts that go into the tax bills. Rather, I’d like to see the entire thing scrapped and re-imagined, using the sorts of novel data visualization techniques that are radically re-shaping the way some organizations connect with audiences.

Great examples abound, and here are some of the better ones: RSA’s use of white board animation in “knowledge visualization”; and the amazing “data journalism” on news sites like The Guardian or the New York Times’ Fivethirtyeight blog. Ian Chalmers, of Pivot Design Group, says a growing number of consulting firms now specialize in helping organizations present data in highly imaginative ways, such as Visual.ly, Infostethics and Fathom. London has its own “Data Store.”

There are lots of people in the corporate world who get this point, by the way. The Canadian Institute for Chartered Accountants (CICA) hands out annual awards for excellence in financial disclosure and reporting, lauding companies like Potash Corp. for the clarity with which they connect with their investors and other stakeholders. (Disclosure: I write for CA Magazine, which is published by the CICA.)

A municipality, of course, has very different goals than a publicly traded company. But they both have a vested interest in effectively communicating financial information to their respective audiences. Indeed, there’s a growing body of academic literature showing that clear financial reporting is connected to share performance. Put simply, the better the disclosure, the happier the investors.

This topic came up at last week’s lively #topoliWTF event, at the Tranzac Club. One participant wondered why, for example, we can’t look to the budget documents to find out the per capita spending on libraries. Excellent question.

Unlike many annual reports, the city’s budget documents also suffer from chronic amnesia. Case in point: not only would it be useful to know the per capita spend on libraries; it would be helpful for citizens to see how that ratio changes over time, whether or not it is linked to changes in traffic in the libraries, and how the ratio of library users to the general population evolves from year to year.

If voters could see that per capita spending was growing faster than actual usage, they might interpret that data point as a warning sign of mismanagement. But if they noticed that increases in library traffic had exceeded the budgetary allocation per resident, they might say to councillors that more investment is needed.

Here’s another example of unhelpful budget information: inevitably, the city each year trots out a bar graph showing what a typical homeowner pays for various services. But wait! This is for someone who owns a nearly half million-dollar home. Last I checked, about 50% of the city’s residents are tenants, so this break down is literally meaningless because they never see a property tax bill. Imagine if a firm like Bombardier only sent investor packages to half its shareholders. They’d sell, fast.

There are surely thousands of ideas for recasting and improving the annual budget numbers in ways that provide greater analytical clarity for ordinary people.

So how to get from dark to light? Obviously, it’s not an overnight fix.

My suggestion: council should pass a motion establishing a working group of councillors, city staff, and citizens to begin a consultation on what sorts of information should be in the budget, in what form the data can be better presented, and some overarching principles on how the city should be presenting information.

Armed with that kind of framework, the city should then issue an RFP asking data visualization companies to propose solutions that incorporate the ideas collected through the consultation. Lastly, get it done by the next term of council. (By the way, the expenditure belongs in the capital budget column because the investment can be amortized over many years.)

Why spend money on something like this when there are roads to fix and child care workers to pay? For similar reasons that public companies invest in their annual reports: if shareholders have a clearer sense of what firms are doing, they’re better positioned to make good investment decisions.

Translated to the public realm, clearer and more accessible budget information will invariably lead to increased public engagement, better scrutiny, improved decision-making and therefore more responsive local government.

As we embark on yet another parade of three-minute pleas that mostly fall on deaf ears, it’s hard to imagine why anyone could be satisfied with the status quo.

11 comments

Well said, John: Part of my work includes doing financial analysis for non-profit organizations, so I consider myself fairly savvy when it comes to reading budgets. But I end up feeling like some kind of idiot when I confront the City of Toronto’s annual budget document. It shouldn’t require courage and a lot of free time to decode these documents. We need a much better process. Thanks for calling for it.

I’ve seen a lot of budgets in my day, most budgets look a lot like an income statement, but future looking rather then past looking. Most budgets show the actual for the previous year, the actual for the current year to date, and the proposal for the next year, there are usually a set of notes that are applied to numbers that require explanation. You can usually show these numbers in a page or two. The notes can go on for quite a bit, but one of those binders should be able to show all of it, and only be able a quarter filled. Even a corporate budget for a company as large as General Motors, is going to run only a couple of pages, with a couple of more in notes.

I think these huge budget documents are an attempt at obfuscation, if we make is voluminous and hard to read, then nobody will actually care to do so. Even if the average citizen can read a normal budget, the 10,000 page document, makes it too unwieldy to want to do so.

All the average person cares about is total income and how that relates to his tax bill. Someone into accounting probably would like to know total expenses, and whether there is a surplus or a deficit. If a deficit how they are going to pay for it.

For per capita Library data, try pages 15 through 17 of this Toronto document on 2013 TPLibrary budgets. [ http://www.toronto.ca/budget2013/pdf/op13_an_tpl.pdf%5D Released publicly the same day as full 2013 City budget released- Nov 29’12.

Pretty accessible, timely and transparent data I’d say.

I agree that the information that the city gives out is near impenetrable. And when they do give out simplified versions like the one you linked to, they are misleading. Besides only providing a breakdown for homeowners, that graph is misleading. Most readers of that graph would be led believe that the cost of policing averages $624 per household. Along with the other expenses many might believe that the city is providing a decent amount of services for a reasonable amount of money. But the graph does not show that at all. It only shows the portion that the residential class pays on average. It does not account for the amount that the non-residential (commercial, industrial, multi-residential, etc.) contributes. The residential class in Toronto is heavily subsidized by the other property classes.

I suspicion is that council likes the fact that the budget information is so obscure. It allows for them to provide an interpretation that reflects there own agenda in a positive light. Like the impression that Ford gives that Toronto residents already pay too much tax. Or that David Miller was financially prudent. Most residents do not have the inclination to delve into the numbers to call bull on both.

I have found the best source to get an accurate picture of a municipalities financial situation, and compare it between years and even other municipalities is the Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing’s Municipal Performance Measurement Program.

http://csconramp.mah.gov.on.ca/fir/Welcome.htm

@J. You prove my point. That appendix shows all sorts of stats about usage, and they are disconnected from any budgetary numbers, so it’s not easy to determine the spending patterns in relation to the traffic patterns.

J – Pages 15 through 17 give per capita use, not per capita spend. I didn’t see the per capita spend anywhere in the document, much less the per capita spend on the different branches.

Perhaps a better first question is whether there are other comparable big cities that do it better, or whether they are all more or less equally impenetrable. In other words, is there something about municipal governance that leads to inherently confusing budget documentation. Include provincial governments, seeing as how Toronto has a budget that is bigger than those of several provinces. If there are better governmental examples, then let’s draw from those rather than having to start from scratch.

Excellent column about the budget, with even better ideas for how better to communicate and engage people. It’s funny how often critics call for a line-by-line budget to be released. This in fact what happens now, and it is that very same set of binders that is critiqued in the article. Clearly John’s proposal is better.

We live in a city full of ideas, hopes, dreams and money. This city is lucky enough to be wealthy and resourced with amazing capacity. The budget documents you dream of may just be the way to move the debate in this city from “what can we afford? to “what are we capable of!”

Good basis for a new kind of budget debate.

av

Numbers are most often understood visually, yet we continually fail at good, cutting edge visual communication. Hiring one of the firms Lorinc suggests would be money well spent.

I also believe that the “Real Money, Real Time Ward-Based Participatory Budgeting” I witnessed in Brooklyn and Harlem last year could be Toronto’s Ultimate Game Changer.

While Chairing the Budget Committee, I was leery of the PB concept but today there is a working model not far from home in Chicago and NYC that is meaningful and manageable.

Bottom line for me: Budget Binders should stay for Councillors who get paid good money to read them, but if we improve how we Talk Budget with Torontonians, we will get a solid Budget Direction from Torontonians.

J’s response to Lorinc and David: per capita stats are ‘performance indicators’ – OK, lets’ go there … City does this every year, compared to other cities [http://www.toronto.ca/legdocs/mmis/2012/ex/bgrd/backgroundfile-46957.pdf#page=159]; or, better yet, since TPLBoard is run by a mixed political/community Board, what do they themselves do to set objectives and measures…service standards (pages 1-8)& performance stats (pages 9-12) they set this fall…[http://www.torontopubliclibrary.ca/content/about-the-library/pdfs/board/meetings/2012/oct22/09b_2.pdf]. Point = useful stuff is out there, reasonably accessible, transparent and timely. Try that with your federal government level – say, for F35s; or your provincial government – say, electricity costs or future OPP costs.

Thanks so much for your insightful column, John. It encouraged me to reflect on participatory strategies (which leave me feeling hopeful but often dissatisfied) and the state’s relationship to data on a broader scale. My reflections are posted here: “on data and public engagement”, http://tmullermyrdahl.org/feminist-urban-futures/