Almost a century before the United Way’s Poverty by Postal Code report (2004) begat the City’s “priority neighbourhood” strategy (2006), Toronto officials found themselves confronted with an almost identical set of challenges: concentrated poverty, inadequate housing, a dearth of social services, all in a dense urban neighbourhood populated by a large number of recent immigrants.

“The Ward,” an early 20th century “slum” bounded by Yonge, University, Queen and College, could be described as Toronto’s original priority neighbourhood. The area was a classic “arrival city,” to use the phrase coined by the Globe and Mail’s Doug Saunders — a zone of transition for the first sustained wave of non-Anglo-Celtic migration to Toronto. Moreover, the significance of the city’s response to the poverty of this neighbourhood cannot be overstated.

Despite that, the Ward has been almost totally erased from the surface of the city. Only a handful of original buildings remain, and there’s not a single historic marker to acknowledge a poor but vital neighbourhood that taught Torontonians crucial lessons about tolerance, public health, and the uses of public space.

Between 1881 and 1921, Toronto’s population exploded, leaping from 86,000 to over 500,000. Until the 1890s, the Ward was primarily an anglo-saxon working class community, with some Irish immigrants. By the turn of the century, however, thousands of newcomers had settled in the Ward; most were Chinese, Italian or Eastern European Jews fleeing Czarist pogroms, although there were Scandinavians, Africans and Greeks. Over-crowding became a major problem. By 1911, according to this York University essay by Michael Chrobok [PDF], two-thirds of the dwellings in The Ward had four to nine residents, and a fifth had over ten.

The conditions, clearly visible from E.J. Lennox’s “new” City Hall, galvanized officials like works commissioner R.C. Harris and Dr. Charles Hastings, the medical officer of health, who ordered a detailed survey of the conditions in 1911. The so-called slum problem, well known in New York’s Lower East Side and Chicago’s Back of the Yards, was seen as a kind of social contagion, and Hastings warned Torontonians not to be complacent. At the same time, he made it clear that the Ward’s residents had not brought impoverishment upon themselves; the problems had to do with sanitation, education, and public health, not a lack of morality.

Over the next decade, conditions in The Ward influenced a wave of regulatory and social reforms that would accelerate Toronto’s modernization and its attitudes towards immigrants:

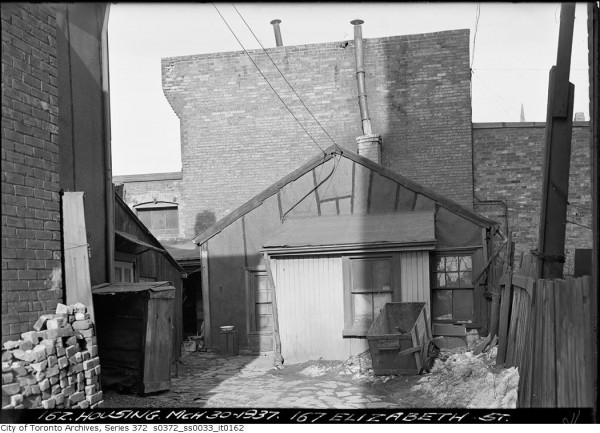

- The City built new sewers and water mains, banned outdoor privies, and passed regulations banning certain building practices – e.g., windowless rooms and laneway shanties — to improve the housing stock;

- Public health inspectors and nurses fanned out in the Ward and other poor areas (Parkdale, Cabbagetown) in an attempt to contain the spread of tuberculosis and educate immigrant women.

- Municipal officials promoted breast-feeding and vaccination, ordered dairies to pasteurize milk and established a municipal abattoir;

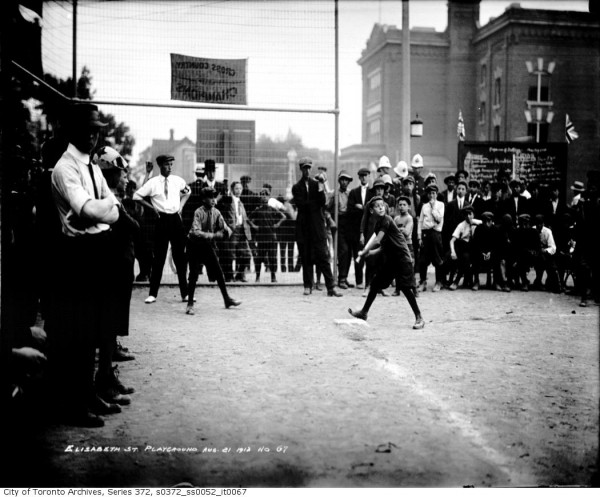

- The City established Canada’s first supervised playground — the Elizabeth Street Playground, located on what is now the north-east corner of Sick Kids. For over 30 years, generations of immigrant kids who lived in The Ward congregated there to participate in organized sports.

- The influx of immigrants to the Ward prompted Elizabeth Neufeld, a Jewish activist from Baltimore, to establish Central Neighbourhood House at 84 Gerrard, just a few doors west of Terauley (now Bay Street). Canada’s first settlement agency, CHN had no church affiliations and didn’t seek to convert the children and mothers who participated in programs and clubs ranging from boxing to sewing.

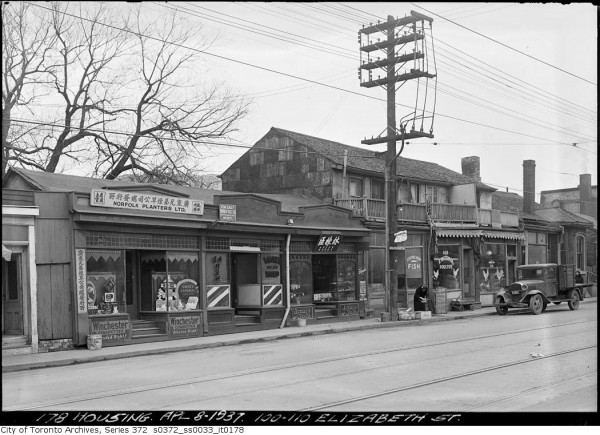

By the early 1930s, The Ward had evolved into a lively immigrant enclave, and eventually became Toronto’s original Chinatown.

Yet public officials remained uncomfortable with The Ward’s proximity to Toronto’s political and financial institutions. Beginning in the late 1890s, municipal officials had generated successive plans for a civic square and public buildings for the blocks north of Queen. In 1934, a royal commission led by lieutenant governor Herbert Bruce, a surgeon, recommended that Toronto build orderly public housing complexes to replace the “sordid” housing in areas such as The Ward and Moss Park.

In 1946, city council passed a bylaw banning private development south of Dundas, and proceeded to expropriate much of Chinatown in order to create space for new public administrative buildings and a square. In the north end, the hospitals had begun to expand, and land was assembled into larger blocks for uses like the bus station. By 1966, when Viljo Revell’s City Hall opened, Nathan Phillips Square had wiped out much of the Ward’s southern tier. Today, Elizabeth Street — which was to The Ward what St. Urbain Street was to the Montreal of Mordecai Richler’s youth — is a soulless connector that bears no trace of the role it once played.

During the closing days of David Miller’s term, former councilor Howard Moscoe, whose grandparents lived in area, promoted a plan to create an immigration museum about The Ward at City Hall. But the idea appears to be on ice thanks to budget cuts and the resources required for the 1812 commemoration.

But perhaps the City’s heritage officials, or even private philanthropists and history buffs, should push for something else — a series of public markers and explanatory plaques, at a minimum, or — dreaming here — a more ambitious venture modeled on the extraordinary Tenement Museum in New York’s Lower East Side.

What’s clear is that this fascinating and enormously influential neighbourhood should be rescued from the amnesia that has long afflicted Toronto.

The Ward today is a ghost city. It needn’t remain that way.

photos from City of Toronto Archives

4 comments

Lorinc neglects to mention that St. John’s Ward was the settlement area for African Americans in Toronto in the 19th century.

The Central Neighbourhood House, founded in 1911, was perhaps the Canada’s second settlement agency, but the Evangelia Settlement established in 1902 by Sarah Libby Carson and others was clearly the first. For much of its history Evangelia occupied buildings at the northeast corner of Queen and River Streets built around “Rivervilla,” the former home of Thomas Davies, the brewer. The jumble of structures that obscured the house was torn down in 1974 to permit the Toronto Humane Society to be built on the site.

For those interested in the history of local settlement houses, there’s more on Evangelia in this scholarly essay: http://historicalstudiesineducation.ca/index.php/edu_hse-rhe/article/download/1552/1642

For more on the earliest playgrounds in Toronto and the movement that led to their establishment, see the article by Erica Simmons in Spacing’s upcoming print issue.