Over the next several weeks, Spacing will be publishing a series of articles from Concrete Toronto: A Guidebook to Concrete Architecture from the Fifties to the Seventies (Coach House Books, 2007) as a companion of Spacing’s summer 2013 issue focused on Modernism. The following article, “Why Concrete Toronto?” explains the editors’ interest in this topic, and serves as an introduction to our series on some of Toronto’s classic works of concrete modernist design.

![]()

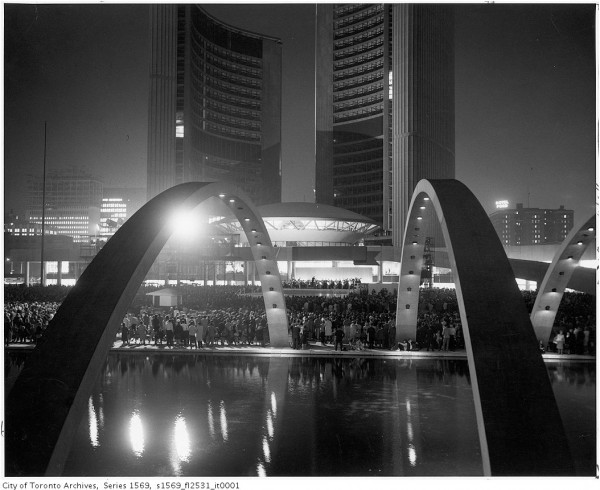

This publication celebrates the concrete architecture that was built in Toronto in the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s. This important period was a time of immense prosperity, when considerable public and private investment had a major influence in shaping Canadian cities. But more significantly, we now suffer a cultural amnesia about this period; we remain critical yet uninformed about its architecture and leave its very large impact on our environment without thoughtful assessment. An appreciation for the architecture of the recent past is a contemporary cultural blind spot. If the making of architecture and the making of cities are inexorably linked, it is clear that the understanding of one requires an understanding of the other. A better appreciation of our recent architectural past gives us greater continuity with the intent, knowledge and ambition of previous generations and a stronger sense of our direction as our city continues to grow.

This publication celebrates the concrete architecture that was built in Toronto in the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s. This important period was a time of immense prosperity, when considerable public and private investment had a major influence in shaping Canadian cities. But more significantly, we now suffer a cultural amnesia about this period; we remain critical yet uninformed about its architecture and leave its very large impact on our environment without thoughtful assessment. An appreciation for the architecture of the recent past is a contemporary cultural blind spot. If the making of architecture and the making of cities are inexorably linked, it is clear that the understanding of one requires an understanding of the other. A better appreciation of our recent architectural past gives us greater continuity with the intent, knowledge and ambition of previous generations and a stronger sense of our direction as our city continues to grow.

At the centre of our limited understanding of the architecture of this era is the confusing term Brutalism, now broadly used to cover the style of almost all concrete buildings erected during the period. The word comes principally from the work of English architects Peter and Alison Smithson, who, with their friend Reyner Banham, used the phrase the New Brutalism to propose a practical, honest and no-nonsense antidote to what they regarded as the frivolous modernism of the 1951 Festival of Britain. Banham’s early-1950s book was entitled The New Brutalism: Ethic or Aesthetic?, and the title tellingly underlines the implicit contradictions in the Smithsons’ work – can an architectural idea be equally about ethics and aesthetics?

But Brutalism also applies to Le Corbusier’s use of raw concrete — known in French as béton brut — for the exposed finish of his buildings such as the Unité d’Habitation, completed in the early 1950s. Today we’re left uncertain to what degree Toronto architects were influenced by the Corbusian French béton brut, which has some of the same connotations as champagne brut or diamant brut — a diamond in the rough — and how much they were influenced directly by the Smithsons’ English utopian experiments in social housing … or if neither was actually a strong reference. A closer look suggests many other non-Brutalist cultural connections fed into the design of Toronto’s concrete buildings. They are as diverse as Rudolf Schindler, the extraordinary Californian architect for whom Irving Grossman had worked, or the engineering innovations of Maillart or Nervi, which influenced Morden Yolles, or simply the sheer impact of the immigrant populations who brought the right skills and trades at the right time.

Richard Serra’s rare 1970s concrete sculpture in King City shows that concrete was a material for artistic experimentation (see photo below). At the time, concrete must have seemed incredibly liberating for architects, allowing them to move beyond many of the limitations of earlier construction materials. Concrete could be compressive and tensile and could be made into almost any form imaginable. Where architecture had previously been built on a codified set of values for materials and techniques, like status goods, concrete was inexpensive, locally produced and readily available, and it broke from established practice. Concrete was the perfect material for the postwar period.

But as we celebrate this architecture, we recognize that it will pose interesting questions about taste, as many of the buildings included in this publication still remain controversial both for architects and the general public.

Why is it that we like some buildings and dislike others? And are our likes and dislikes more valid than those of others? These are questions worth asking, but there are no simple answers. We can remind ourselves that values, like tastes in fashion, will change. We can remember that until the 1970s, Toronto’s Old City Hall was regarded with disdain, as obsolete, fussy, oppressive and cumbersome – all too Victorian, in a bad way. Or we can recognize that our values in architecture, even beyond issues of taste, still flow from evolving fields of cultural production and consumption that establish the context for valuation.

We can point out that buildings old and new all need to be assessed on what they contribute to the community as a whole, and that positions and arguments will often vary. As buildings age, they may attain a canonic value — something like that which we see in Old City Hall. We don’t mean to imply that all these concrete buildings have now reached this canonic or heritage value, but we propose that many may do so.

Beyond the question of taste, the more important direction for questioning is what we can learn from the recent past. Whether through knowing our history better we can build on its strengths and enrich our contemporary environment. Whether through seeing these buildings through fresh eyes we can see new possibilities. These concrete buildings, a significant part of the built fabric of the city, are ready for a careful second look.

— Graeme Stewart and Michael McClelland