Over the next several weeks, Spacing will be publishing a series of articles from Concrete Toronto: A Guidebook to Concrete Architecture from the Fifties to the Seventies (Coach House Books, 2007) as a companion of Spacing’s summer 2013 issue focused on Modernism.

![]()

First small proposition: Recognize the CN Tower as a National Historic Site.

It currently is not. Look at the CN Tower from a distance. Now picture that the Eiffel Tower is about three-fifths its height. Or that the Great Pyramid of Giza is only one-quarter its height. Or that Big Ben is a pocket watch in comparison. You would need six Big Bens, one on top of the other, to match the height of the CN Tower. Obviously height isn’t everything, but, recognizing that Toronto has had the tallest free-standing structure in the world since 1976 [editor’s note: the record was held between 1976-2010], one does ponder why it has so little emotional impact on our urban psyche when these other structures carry such iconic weight. Possibly the closest comparison to the CN Tower is not the Eiffel but the Ostankino Tower in Moscow. The Ostankino Tower was erected in 1967 and was the tallest free-standing structure in the world for the 10 years before the CN Tower was built. The Ostankino is a mere 13 metres shorter, and one can imagine the Cold War competitiveness at play. Built by the national railways as they expanded into telecommunications, the CN Tower was not so much about Toronto, but more about the play of nations and Canada within a global context. Canada’s role in international affairs during the late 1960s and early ’70s was felt to be one of strength, industry and optimism. Today we are as distanced from that comfortable nationalism as we are from the CN Tower.

Second small proposition: Provide the CN Tower with a public street address and a dignified urban setting.

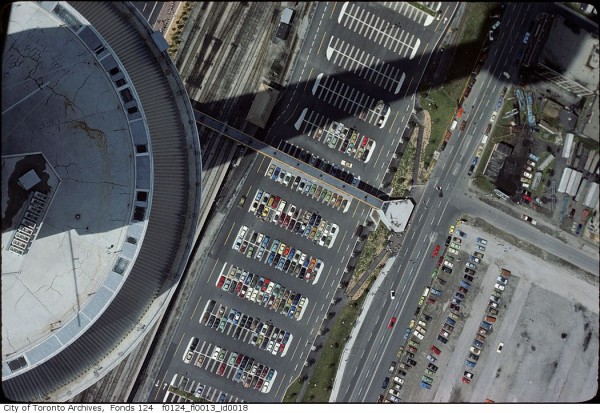

Connect the tower to the city. Now try to get closer to the CN Tower. Really close. Go up and try to put your arms around it – yes, that’s right, try to give the tower a big hug. It is difficult to get there because the unfortunate design that clutters the base makes close contact almost impossible. While most Torontonians have ridden to the top of the tower with visiting friends or relatives once or twice, few have experienced it as an object in the street, as it is so concealed in its context. A basic rule of urban planning is that landmarks require carefully considered settings. They can even be used to organize the public space around them – just think again of the Eiffel Tower or even of the Ostankino, which sits in an amazingly large open space. The siting of the CN Tower is not what it could be. It is hemmed in by the operating rail tracks and blocked from the downtown by the perfectly functional, perfectly necessary, but clumsily designed Metro Convention Centre. The convention centre might be considered the clumsiest large-scale building in the city if it weren’t for the CN Tower’s massive friend, the Rogers Centre, which sits far too close to the tower for the creation of any generous public space.

Third small proposition: Let the CN Tower remind us to think big; it is essential for well-planned city growth.

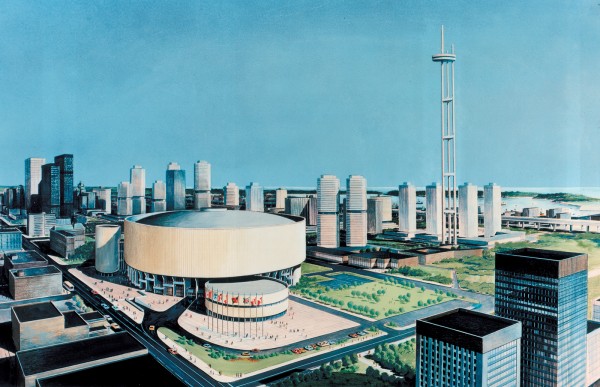

The CN Tower was all that was built of the Metro Centre Plan — a gigantic proposal for the 1960s and ’70s urban renewal of the CN/CP railway lands designed by WZMH and John Andrews (the eventual architects for the CN Tower). The plan was in many ways an imposition on the city. It called for the demolition of Union Station and it represented urban renewal as infrastructural change, at a time when Toronto was beginning to focus on an urbanism that valued exclusively the qualities of the smaller scale, primarily experienced in our charming older neighbourhoods. For years afterward the railway lands lay undeveloped and only recently have they been built upon. A comparison between the Metro Centre Plan and what in fact has been built around the CN Tower would be constructive. I don’t regret at all that the Metro Centre Plan did not go forward, but we may find that by ignoring and denying the infrastructural scale of city development, it has snuck in through the back door. The CN Tower reminds us that cities work at many scales, and we need to consider them all.

Fourth small proposition: Lighten up, Toronto. Toronto needs its superheros. Toronto needs to connect with its aspirations. Sometimes it is okay to be world-class.

I was living in Japan when the CN Tower was being completed, and my then-teenaged brother Andrew reported to me frequently on how quickly the tower was rising. He was not a big architecture fan, but his enthusiasm for the building of this mammoth construction was genuine, engaged and popular. He told me he had lined up so that our names could be put in a time capsule that was placed at the top of the tower. There was a sense of positive energy about modernity in the city that worked. Torontonians were proud of the CN Tower. The CN Tower was a superhero. While I am still impressed by the tower’s elegance and phenomenal monumentality, it is true that most Torontonians are no longer buoyed by its optimism. Our current cultural mood is overcast with irony and negativity, far removed from the more innocent times of the CN Tower’s construction. The tower stands as our Ozymandias, a marker of an almost distant past.

– by Michael McClelland

3 comments

For me the key to the CN Tower is our treatment of John Street. We need to find a way to “reconnect” John St. from north of Front St. to south of the railway corridor where the roundhouse is.

Right now John St. ‘ends’ like Bay St does … into the gaping maw of a parking garage entrance. Pedestrians were shuffled to the uneven steps on the east side of John, and the view of the tower and the bridge was blocked off by the overhang of the Convention Centre building.

We need to open up that access point, make the John St bridge into a public space, and clean up the space at the base of the CN tower.

A John St. ‘Pedestrian Mall’ would be a start.

Cheers, Moaz

I agree that it is great to be able to walk right up to a tower like this. There Eiffel Tower looks great from a distance, but it’s when you get right up underneath it, or next to one of the “feet” that you really feel like you’ve SEEN it. The CN tower is a bit of a distant friend in a way.

I think the lighting of the CN Tower at night that has been in place for the last few years has helped tremendously. I think it really helps people to see the Tower with again – in a new way…and recognize it as the spectacular feature that it is.