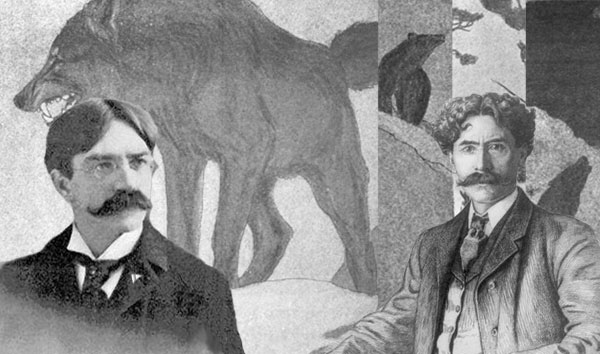

Once upon a time (by which I mean the late 1800s and early 1900s) stories about intelligent, anthropomorphized animals were all the rage. The trend had been sparked by Darwinism and took off with the publication of Black Beauty in 1877. After that, the classics came quick: The Jungle Book, The Wind In The Willows, White Fang and The Call of the Wild, Beatrix Potter books and the tales of br’er rabbit. Among the literary giants of the “animal stories” age were a few Canadian authors. One, Margaret Marshall Saunders — who would spend her later years in Toronto — wrote a novel about an abused dog named Beautiful Joe. It became the first Canadian book to sell more than a million copies. But Saunders wasn’t alone. There were two other major animal story authors with connections to Toronto: Sir Charles G.D. Roberts and Ernest Thompson Seton. Both were Canadian. Both were incredibly popular. Both had awesome moustaches.

Roberts was from New Brunswick. While he was there, he wrote such proudly nationalistic, nature-loving verse that he was hailed as The Father Of Canadian Poetry and was known as one of the Confederation Poets. But even back then it was hard to make a living writing poems in Canada, so he moved to New York City and started writing prose. Books like The Kindred of the Wild, told from the perspective of the animal characters, made him one of the very first world-famous Canadian authors — the first Canadian writer ever knighted for his work. Eventually, he’d end up living in Toronto, where, like Saunders, he spent the final years of his life. By the time he died in the 1940s, he was recognized as “Canada’s leading man of letters.”

Seton, meanwhile, grew up in Toronto. He developed a passion for nature by exploring the wilderness of the Don Valley as a child. He built himself a cabin and spent long hours observing the animals and birds, filling notebooks with sketches and meticulous descriptions. The wildlife he encountered in those youthful days would appear in his writing for years to come.

He too would eventually end up living in the United States. There, he co-founded the Boy Scouts of America and wrote the first edition of The Boy Scout Handbook. Soon, his Canadian roots would be used as an excuse to kick him out of the organization after he criticized its militaristic bent. Luckily, he still had his fiction. Books like Lobo, Rag and Vixen and Wild Animals I Have Known earned him a place among the ranks of the world’s most famous animal story authors.

Roberts and Seton are still celebrated as pioneers of a distinctly Canadian literature. The Canadian Encyclopedia credits them with the creation of “the one native Canadian art form.” And when Margaret Atwood explored the idea of a national literary identity in Survival: A Thematic Guide to Canadian Literature, she dedicated an entire chapter to the animal stories. “[They] are told from the point of view of the animal,” she wrote. “That’s the key: English animal stories are about the ‘social relations,’ American ones are about people killing animals; Canadian ones are about animals being killed, as felt emotionally from inside the fur and feathers.”

But not everyone loved those stories. Take, for instance, John Burroughs. He was a famous American naturalist and essayist, the “Grand Old Man of Nature” armed with a beard so awesome it nearly rivaled the Canadians’ own facial hair. He attacked Roberts and Seton (along with a few other writers) in an Atlantic Monthly article called “Real and Sham Natural History”. Offended by what he claimed to be the lack of hard science behind their stories, he accused them of misleading the world’s children with tales of clever and compassionate beasts, denouncing them as “yellow journalists of the woods”.

His article kicked off a fierce battle. Some of the writers fought back. There were more articles. Magazine features. Book prefaces. A full-page editorial in the New York Times. The “Nature Fakers Controversy” raged on for years, only coming to an end once Burroughs convinced Theodore Roosevelt, the hunt-loving President of the United States himself, to wade in on his side. Though Roosevelt knew Seton, admired Roberts’ writing, and admitted it wasn’t appropriate for the President to get involved, he condemned the authors’ lovable animal stories as “an outrage”, “a genuine crime” and “an object of derision to every scientist worthy of the name, to every real lover of the wilderness, to every faunal naturalist, to every true hunter or nature lover.”

And that was that. The controversy died down. Burroughs and Roosevelt had won. The official wisdom declared that animal stories were bad for society. Case closed.

No one ever read The Jungle Book or Black Beauty or The Call of the Wild ever again.

A version of this post originally appeared on The Toronto Dreams Project Historical Ephemera Blog.

Image: Charles G.D. Roberts left; Ernest Thompson Seton right.

One comment

I wasn’t aware that “The Jungle Book,” “Black Beauty” and “The Call of the Wild” were written by Canadian authors or that they share any common theme past a general sympathy with animals. In “The Jungle Book” the animals are antagonists as well as friends to the central human character; “Call of the Wild” is presented from an animal’s point of view but is without the human-like dialogue of “Black Beauty;” and their critiques of human society are polar opposites.