“What war?”

In the summer of 1914, A.Y. Jackson was far from home, high among the peaks of the Rocky Mountains. He was there to paint. This was back in the earliest days of the Group of Seven, years before they used that nickname. Jackson was still new to the group; the others had only recently convinced him to join their efforts to change the Canadian art world forever — and with it, the way Canadians saw their own country.

Even before they met him, the other artists admired Jackson. His style was deeply influenced by his studies in Paris, at the heart of the Impressionist revolution that had yet to reach Canada. The group saw Jackson’s work — particularly a painting called The Edge of the Maple Wood — as the example they wanted to follow. So they and one of their patrons offered him free room and board for a year if he was willing to move from Montreal to Toronto and do nothing but work on his art. They even had a brand new building to put him up in: the Studio Building in Rosedale. He accepted.

But in those early days, the group’s paintings were terribly controversial. Established critics dismissed them in much the same way Van Gogh, Matisse and Picasso had been dismissed. “The Hot Mush School,” they called them. “A horrible bunch of junk.” “The figments of a drunkard’s dream.” “Daubing by immature children.” “A spilt can of paint.”

Luckily, not everyone agreed with those critics. Some people were thrilled with the way Jackson and the others were using vivid colours and Impressionist techniques to capture the spirit of the Canadian landscape. When the Canadian Northern Railroad built a new line through the Rockies, they commissioned Jackson to travel with their construction camps as they worked along the Fraser River. That’s how he made his first trip out West.

While he was in the Rockies, Jackson would leave the camps behind for days on end, hiking up in into the mountains with a guide. “We took many chances,” Jackson remembered later in his autobiography, “sliding down snow slopes with just a stick for a brake, climbing over glaciers without ropes, and crossing rivers too swift to wade, by felling trees across them.”

It was at the end of one of these “scrambles” that he heard the news. When he returned to camp, an engineer was waiting for him. “What do you think about the war?” he asked the painter. It was the first Jackson had heard of it.

Before long, he would be all too familiar with the First World War, fighting on the front lines. But for now, it seemed a long way away. As the military might of Europe shifted into gear, Jackson kept painting. Most people thought the war would be over soon; there didn’t seem to be any pressing need for the artist to join the fight. Instead of heading back to Toronto, where young men were lined up outside the Armouries on University Avenue waiting to enlist, Jackson headed straight from the Rockies to Algonquin Park. There was someone waiting for him there.

Tom Thomson was one of the most promising young artists in Toronto. But Thomson found that hard to believe. He had a steady, paying gig at Grip Ltd., a downtown design firm where many of the Group of Seven artists worked. He was known as the most accomplished outdoorsman of them all; it was Thomson who first fell in love with Algonquin Park and introduced it to the others. But he lacked their confidence when it came to his art. He worried that if he quit his day job, he wouldn’t be able to make a living off his paintings. And so, as part of Jackson’s deal to get a free year in the Studio Building, the others also asked him to take Thomson under his wing. The two artists would share a studio on the top floor. And while Thomson taught Jackson about life in the bush, Jackson would teach Thomson about painting.

The two met in Algonquin that autumn for their very first sketching trip together. While Arthur Lismer and Fred Varley (two future members of the Group of Seven who had recently emigrated from England) stayed in a lodge with their families, Jackson and Thomson roughed it in the bush: living in a tent, travelling by canoe and working on birch panels small enough to be carried through the wilderness. That fall, they made sketches that would lead to some of their most famous work. Jackson’s The Red Maple was a result of that trip. And so was Thomson’s Northern River.

Meanwhile, six thousand kilometers away, young men were facing a very different reality. “There was a war on too,” Jackson later wrote, but “in Algonquin we heard little about it and hoped it would soon be over.”

Of course, it wouldn’t be. The war on the Western Front had kicked off with a big, fast, German drive into France and an Allied counteroffensive that pushed them far back. But now that quick, dramatic war of sweeping movement — the kind everyone had been expecting — was settling into a grueling stalemate. That September, in order to avoid being driven back any further, the Germans dug the very first trenches. The French soon followed suite. By the time the artists got back from Algonquin, it was already becoming clear that this would be a new, more horrifying kind of war. And not a short one. “When we reached Toronto,” Jackson wrote, “we realized that we had been unduly optimistic, that the war was likely to be a long one, and that our relatively carefree days were over.”

He tried to get back into the swing of things at the Studio Building, turning sketches like The Red Maple into full canvases. “But I could not settle down to serious work. The war made me restless.” With his free year at the Studio Building coming to an end, Jackson decided to head back to Montreal and join the army.

As it turned out, it would still be a few months before he finally signed up. The news from Europe shifted again and it seemed, again, as if it might be a quick war. Jackson seized the opportunity to take another sketching trip, this time to one of his favourite spots in rural Québec.

But in April, the Germans successfully deployed a deadly new weapon for the very first time: chlorine gas. In Belgium, near the town of Ypres, a thick cloud of poison yellow smoke descended on trenches full of French, Moroccan and Algerian troops. They say six thousand people died in the first few minutes: suffocating, lungs burning, frothing at the mouth, cut to pieces by German guns. The Germans attacked and drove the Allies back to a spot near the village of St. Julien, where Canadians rushed to plug the hole in the line, holding urine-soaked handkerchiefs over their faces as feeble protection against the deadly fumes. Three-quarters of them would die, too, but they would hold the line and keep the Germans at bay. That was just the beginning of a long, bloody battle — the same one that would inspire another Canadian, John McCrae, to write “In Flanders Fields.”

“At the railway station one morning I heard the first news of the Battle of St. Julien,” Jackson wrote. “I knew then that all the wishful thinking about the war being of short duration was over.”

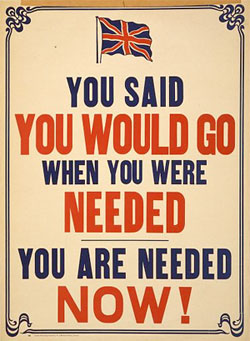

Finally, he saw this recruitment poster:

It “ended any doubts I had about enlisting,” he said. A few months later, he was on his way to the front lines.

Still, while Jackson was willing to fight, he was far from being seized with a patriotic lust for battle. His letters made that perfectly clear. “I’m a Social Democrat,” he wrote to his sister from the battlefields of Belgium, “and don’t believe in war.” He scorned the wealthy, Empire-loving Canadians who glorified the war from the safety of home while the poor were forced to fight it. “I don’t think I ever in my life took so little pride in being British,” he wrote in a second letter. “The rough neck and the out of work far outnumber the patriot. Volunteers by pressure… when you hear all the bosh talked and written about our precious honor, Christian ideals, etc. it just about makes you sick… people who entrust their national honor to men they would not allow to enter their houses in times of peace are not worth fighting for.”

Before he’d even left for Europe, Jackson wrote, “I wish we could send all our politicians to the front.” And later, he added that warmongering members of the clergy would benefit from the same treatment. “At the front we would see examples of self sacrifice and sublime courage by men the church would regard as outside the law. His faith in the church might weaken but his faith in humanity would be better stuff after it.”

When Jackson had first signed up, Lawren Harris (another, wealthier artist in the group) had offered to buy him a commission as an officer (and all the preferential treatment that came with it). But Jackson refused, preferring to earn his rank through experience. “This Canadian army,” he wrote, “would be a far finer machine to my mind if all class distinctions were done away with, and officers lived under exactly the same conditions as the men…”

It was early in 1916 that Jackson ended up in the trenches just outside Ypres, not far from the spot where the St. Battle of St. Julien had raged a year earlier. It was a bombed-out, blood-soaked mess. “The flag waving was over,” he wrote. But he did see some haunting beauty in the desolation. “Flanders in early spring was beautiful, as was Ypres by moonlight and the weird ruined landscapes under the light of flares or rockets.”

That summer, the Germans launched an attack against the high ground held by the Allies outside the town. Jackson was there “crawling along a trench in Sanctuary Wood, and an aeroplane circling overhead like a big hawk, signalling to the artillery who were trying to blow us up. It was a day of glorious sunshine and only man was vile, in general, individually they were magnificent.”

Once the Germans had pushed the Allies off the high ground it was up to the Canadians to counter-attack — the first time our army had ever been given such a task. It was, according to the official British history of the war “an unqualified success.” The Canadian forces developed new methods for fighting this new kind of brutal war — changing, for instance, the number of artillery barrages before they went over the top, so the Germans wouldn’t know when they were coming.

Now, nearly 100 years later, a museum stands on that spot, still run by the grandson of the farmer who owned the land. Nearby, a monument has been erected as a memorial to the Canadians who died there. Some of the craters and the trenches where they fought are still there, too, preserved by the museum. In Toronto, we remember the battle every year with a parade at Fort York. We call it “Sorrel Day.”

Jackson survived the barrages, the attack and the counter-attack, but it was hard for anyone to last very long in that devastated place. A week later, during a German bombardment, he was wounded. It got him in the hip and the shoulder.

He was taken to a hospital in France and then to England to recover. That’s where got a letter delivering tragic news from Canada.

When Jackson had left Toronto to enlist, Tom Thomson had stayed behind to paint. He had a medical condition that kept him out of the army. But at that point, his free year in the Studio Building was over too, and without someone else to help make rent, he was forced moved into the shed out back instead. He spent the warmer months away on sketching trips in the northern bush, while he spent the snowy months holed up in the shack on the slopes of the Rosedale Valley, deeply immersed in his work. There, he would paint some of the most famous canvasses in Canadian history, works like The Jack Pine (now in the National Gallery) and The West Wind (now in the AGO).

All the while, he worried about the war. The shed, as rustic as it was, was still only a few blocks away from the intersection of Yonge and Bloor, where thousands of soldiers marched by on their way to war. The military was all over the city. And Thomson had friends on the other side of the Atlantic to worry about, too. “I can’t get used to the idea of Jackson being in the machine,” he wrote to another artist in the group, “and it is rotten that in this socalled civilized age that such things can exist…”

Jackson would survive to see the end of the war, but Thomson wouldn’t be so lucky. During the summer of 1917, he took another trip to Algonquin. It would be his last. The accomplished outdoorsman disappeared on a canoe trip and was found eight days later, floating dead in Canoe Lake, fishing wire wrapped around his leg. At the time, he was still barely known outside the small group of artists in Toronto. But over the course of the next few decades, his fame grew — and so did the legend of his death. A century later, he’s hailed as one of the most famous Canadian artists ever and his suspicious accident is one of our most infamous mysteries.

But for Jackson it was a very personal tragedy. “I could sit down and cry to think that while in all this turmoil over here… the peace and quietness of the north country should be the scene of such a tragedy,” he wrote in a letter home. “Without Tom the north country seems a desolation of bush and rock. He was the guide, the interpreter, and we the guests partaking of the hospitality so generously given.”

In his autobiography, Jackson remembered, “The thought of getting back to the north country with Thomson, and going father afield with him on painting trips after the war was over, had always buoyed me up when the going was rough. Now I would never go sketching with Tom Thomson again.”

And things looked like they were about to get even worse. Jackson had recovered from his wounds just as the Allies were getting ready for a big offensive — and just as the men in his unit had gotten so sick of the conditions, they were ready to mutiny. Soon, they would be back on the front lines outside Ypres, at the muddy Battle of Passchendaele, where hundreds of thousands of men would die in just a few short months. Meanwhile, Jackson was reaching the end of his tether — he had been worn down by the war and friends worried he couldn’t take much more of it.

But a few days after he learned about Thomson’s death, Jackson got some good news. He was digging a latrine when an officer interrupted him. The army had a new project and they wanted him to be a part of it.

The man behind the idea was Lord Beaverbrook — a Canadian businessman turned British politician and newspaper baron. He was determined to make sure that there would an historical record of the Canadian contribution to the war. And so, he used some of his own fortune to establish the Canadian War Records Office. Part of his plan was to hire artists to capture the Canadian experience of the war. Eventually, there would be almost 120 of them, producing nearly a thousand paintings by the time it was all over. Jackson was one of the very first who was asked to join the cause. He would paint more canvases for the War Records Office than any other artist.

Now, instead of a gun, his main companion was a sketchbook.

It was challenging work — and not just because he was trying to make art in the middle of a war zone. In the past, battles had tended to be fought by men standing in fields in straight lines; they wore brightly coloured uniforms; artists were commissioned to glorify their exploits. Now, they were hidden away in trenches being torn apart by distant machine guns or blown to pieces by a rain of artillery. The old style of war painting wasn’t going to work. “What to paint was a problem for the war artist,” Jackson wrote. “There was nothing to serve as a guide. War had gone underground, and there was little to see. The old heroics, the death and glory stuff, were gone for ever; there was no more ‘Thin Red Line‘ or ‘Scotland For Ever.'”

Instead, Jackson chose to paint landscapes, much as he did back home in Canada. But these places were more dead than alive, dreadful and haunting, ruined by the ravages of the most destructive war in human history. Individual soldiers were dwarfed by the scale of the devastation around them.

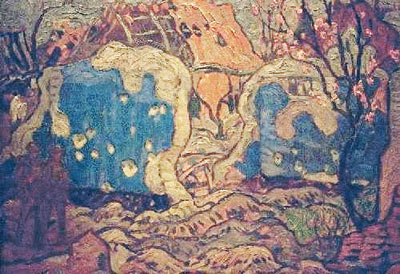

He would start in France, in the same region he had visited years earlier on a sketching trip as a student. “The country around Lens was exciting, in a way, for an artist,” he wrote in his autobiography. “The permanent lines had long been established, and back of them was a swatch, about five miles wide, of seemingly empty country, cut up by old trench lines, gun pits, old shell holes, ruins of villages and farm houses. In the daytime there was not a sign of life. Of all the stuff I painted at Lens the canvas I liked best was ‘Springtime in Picardy,’ which showed a little peach tree blooming in the courtyard of a smashed-up farm house.”

It’s on display at the AGO:

“I went with Augustus John one night to see a gas attack we made on the German lines. It was like a wonderful display of fireworks, with the clouds of gas and the German flares and rockets of all colours.” He wrote notes to go with sketches that night: “Sudden bursts of flame … coloured glow … old house silhouette … Bright green lights behind clouds shining through gas clouds … Blow star a shower of orange.” The painting that resulted, Gas Attack, Liévin, is at the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa:

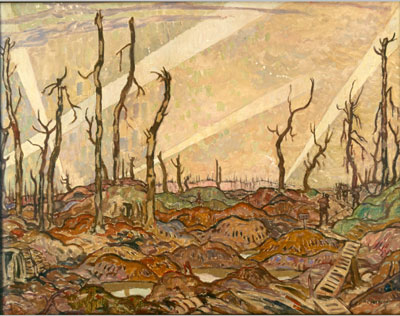

The War Museum also has A Copse, Evening, which one of Jackson’s biographers, Wayne Larsen, writes about in his book, The Life of a Landscape Painter:

“Just west of Liévin, Jackson sketched what would prove to be one of his most striking and memorable wartime images — A Copse, Evening. This eerie scene of dead tree trunks in a wasteland of shell craters and war debris shows a few tiny figures of soldiers making their way along a makeshift walkway of planks. Above them, diagonal searchlight beams slash the sky. The atmosphere is chilling enough, but Jackson’s bitterly ironic title drives home the anti-war message — the copse itself is no more; all that’s left are the skeletal remains of the shattered trees.”

Jackson’s House of Ypres is also in Ottawa at the War Museum:

But Jackson wasn’t the only future member of the Group of Seven who enlisted. Lawren Harris and Fred Varley were also in Europe. Varley ended up working for the Canadian War Records Office, too, producing paintings that were even more disturbing than Jackson’s.

“I tell you, Arthur,” he wrote to Arthur Lismer (one of the British-born artists who had been in Algonquin with Jackson and Thomson), “your wildest nightmares pale before reality. You pass over swamps on rotting duckboards, past bleached bones of horses with their harness still on, past isolated rude crosses sticking up from the filth and the stink of decay is flung all over. There was a lovely wood there once with a stream running thro’ it but now the trees are powdered up and mingle with the soil.”

Varley’s piece, For What?, is also in the collection of the War Museum:

Meanwhile, back in Canada, Lismer was also working for the War Records Office. He was in Halifax, painting the war effort on the home front. And before too long, his subjects would include war ships returning home to Canada, full of soldiers on their way back to their friends and family. The war, after four long, agonizing years, was finally over.

By the spring of 1919, Jackson had joined Lismer in Halifax to paint the final stages of the return to peace. Another one of his most famous paintings came out of those days. Entrance to Halifax Harbour now belongs to the Tate Gallery in England. You can barely even tell it’s a war painting at all; the only sign is a few camouflaged ships in the distance:

Now, with the war over and Thomson gone, Jackson’s darkest days were behind him. He returned to Toronto, to the top floor of the Studio Building, and reunited with the other artists in the group. He had earned an international reputation thanks to his war paintings, and had been accepted into the Royal Canadian Academy of Art. It would take him a while to recover from the war, to regain his enthusiasm for the Canadian landscape. But soon, his momentum was back. A memorial exhibition of Thomson’s work, which Jackson helped to organize, met with the usual disdain from the older critics. The fight within the art world would last for at least another decade. But the tide was finally turning.

Canada had a new sense of itself in the wake of the First World War, and for the first time since Confederation, people seemed ready to support artists who wanted to capture the unique spirit of their own country. Jackson and the others had attracted the attention of younger artists. They were selling their work to the National Gallery. Their war paintings had won glowing reviews from the British press. Soon, they would have their first group show together at the AGO. The year after they returned from the war, they decided to publicly declare themselves as a new movement with a new name. They were called the Group of Seven. And they were going to do exactly what they promised to do: change Canadian art forever.

A version of this post originally appeared on the The Toronto Dreams Project Historical Ephemera Blog. You can find more sources and other related information there.

One comment

Wonderful article about a great man. I remember meeting A. Y. Jackson at the McMichael Art Gallery when I was little. I was always in awe of him.