He was, in a lot ways, something of a Canadian stereotype. He was born in a shack on the Prairies during the winter of 1927. He grew up working on his parents’ farm, ploughing fields and tending cows. When he was older, he worked as a lumberjack in the towering forests of Québec and on the shores of Lake Superior. As a construction worker, he put curbs on the streets of Edmonton and built grain elevators in Thunder Bay. As a waiter, he served the rich and famous at the Royal York Hotel in Toronto. And as a painter… Well, as a painter, he became one of the most successful artists in Canadian history, using scenes from his past to capture the spirit of the nation on canvasses that sell for hundreds of thousands of dollars. His work hangs on the walls of some of the most important art galleries in the world — and in kitchens all across our country. His paintings are praised as being quintessentially Canadian. Books of his work have titles like A Prairie Boy’s Summer, Lumberjack, The Last of the Arctic and O Toronto. He’s been hailed as “Canada’s Norman Rockwell.”

But William Kurelek had a dark side, too. So dark, in fact, that by the end of his life, he was convinced the world was about end in a blaze of Biblical fury. It’s one the reasons his biographer, Patricia Morley, calls Kurelek’s life “one of the strangest stories ever told.”

It all started when he was a child, growing up during the terrible years of the Great Depression and the Second World War. He was a sensitive and artistic boy, bullied at school and bullied at home. “There was a kind of rawness and jungle law indifferent to suffering in those Depression years,” he remembers in his autobiography. He writes about “the chess game of harsh, real life” and his own “intense misery.” As a young student who spoke only Ukrainian at first, he felt ostracized by his classmates. Meanwhile, he describes his father as an emotionally abusive tyrant. Young Kurelek lived in fear; terrified that his father’s strap, spankings and verbal lashings were just the beginning of some even more terrible punishment.

It took a toll on the boy. “[I]t poisoned me internally,” he said. He became painfully shy. Even years later, one of his closest friends said that Kurelek “literally couldn’t look anybody in the face.” Another described him as “so ill at ease he seemed like a programmed robot”. He began to suffer from depression. He was haunted by nightmares and visions. “In them my family were in cahoots with my school enemies… and were plotting to mutilate me or kill me. They were operating a meat chopping machine in the preserves room downstairs into which the victims threw themselves in ectasy. [sic]”

By the end of high school, on top of everything else, his eyes had started to fail him. A blurry spot developed into periods of near blindness and excruciating pain; a particularly cruel trial for a teenager with a passion for art. He would draw with one eye closed — and then the other — as a way of rationing the pain. Soon, he was hooked on pills. And his mood swings got even bigger.

But through it all, he kept pursing his dream: art. That’s what first brought him to Toronto. He enrolled at the Ontario College of Art (which was on Nassau Street back then, in Kensington). At first, he had trouble settling in. “They say Toronto is a cold city to strangers and it was just like that,” he remembered. “The quaintness of it turned into smelly grubiness as I pounded the sidewalks. All I could see now were the garbage cans, the drunks stepping out of taverns and vomiting, the livid night lights, the chipped bricks and cobbles with broken bottles on them, the beckoning lights of houses of ill-repute.” But in time, he developed a fondness for the city. He found a circle of new friends at OCA. And exciting new influences, too.

It was while he was studying in Toronto that Kurelek discovered Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and the Van Gogh biography, Lust for Life; he fashioned himself in their bohemian image. “I rebelled as I understood a proper artist was compelled to do — if he was worth his salt — against conventionality… I was proud of my poverty, of not having proper food, or enough of it, of wearing shabby clothes and not bathing or shaving… proud I chummed with communists and eccentrics, even that I suffered from periods of depression because I believed that out of all this I was destined to produce great art…”

“He was a little like a figure out of Dosteovski,” one of his professors remembered, “cryptic and mysterious. He saw himself as an enigmatic figure, a dramatic figure.” His sister called him “the first hippie.”

Before long, his rebellious spirit had prompted him to drop out, following his education all the way down to Mexico — hitchhiking there and back, sleeping in ditches, under bridges and, on one night, in the bushes on Parliament Hill. He spent a few months living in a Gringo commune of outsiders, hoping to catch on with one of the great Mexican masters like Diego Rivera. But it didn’t work. And the depression and the eye pain followed him south. Finally, he decided that psychotherapy was his best hope for recovery. And since in those days, it was even harder to get help for mental illness in Canada than it is today, Kurelek headed across the Atlantic.

The day after he got off the boat in England, he checked himself into the Maudsley Hospital in downtown London. Mental health facilities were still brutal places in the early 1950s, but Maudsley was on the cutting edge, embracing bold new techniques like art therapy. It was there that Kurelek realized his eye pain might be psychosomatic — a result of stress and depression — and it disappeared almost immediately.

He also made great progress as an artist. Painting became an important part of his treatment; he was even given his own studio to work in. At one point, he checked himself out for a trip to the Continent.In Brussels and Vienna, he was blown away by the detailed canvasses painted by Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Bruegel. They became his most important influences, joining other unsettling artists like Francis Bacon and Francisco Goya.

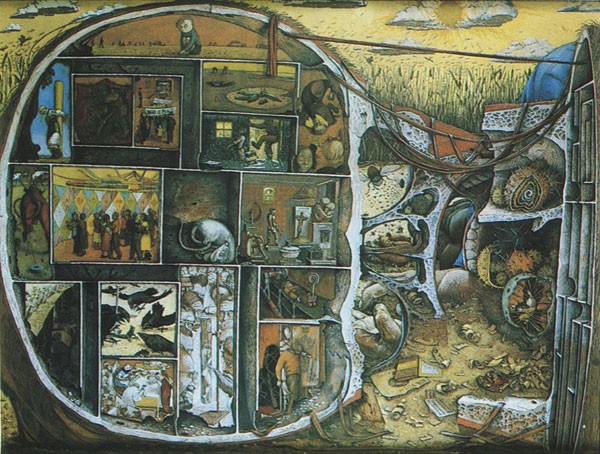

It was in those years — at Maudsley and at another London hospital called Netherne — that Kurelek painted some of his most striking work. But these pieces were far from the charming scenes of Canadiana that would one day make him famous. Instead, they were disturbing, tormented nightmares. The Maze — the most famous of them all — shows a skull lying on the Prairie. It’s been cut open. Inside, there are chambers filled with horrors from the depths of Kurelek’s mind. His father kicking him out into the snow. His half-naked body stuffed into a test tube. Crows tearing a lizard apart. The artist cutting himself open to study his own anatomy. Bullies beating him up as a child. The painting so perfectly illustrated his inner-torment that it became a case study for art therapists. His doctors would eventually ask him to give lectures to classrooms full of psychology students.

But even as he progressed as an artist, Kurelek remained deeply depressed. “No matter how intensely I painted out my store of accumulated fears, hates, disillusionments…” he wrote, “there they were, always dangling along behind me like tin cans behind a wedding car.” Convinced his doctors weren’t paying him enough attention, he turned to self-harm. First, he started cutting himself. Then, he attempted suicide. He took an overdose of pills and slashed his arms and face with a razor. He was lucky to survive.

After that, he agreed to electroshock therapy. Over the course of the next few months, he had a grueling series of treatments — some of them without the usual muscle relaxant. During the first one, he sprained his back; it would bother him for the rest of his life. And as the treatments progressed, he began to lose his memories. At first, it was recent events; then more distant recollections began to fade.

“I was given fourteen convulsion treatments in all,” he wrote, “and it was like being executed fourteen times over. There is an instinctive dread in a person of being annihilated… I could well imagine then something of what it was like going into the gas chamber in Nazi Germany, or to the torture chamber during those misguided religious wars of the 16th and 17th centuries.”

So that’s when William Kurelek started to pray.

Up to that point, he’d been an atheist. But now, he found himself with a renewed interest in religion. Before long, he was attending a nearby church, converting to Catholicism, taking mass at the London Oratory, and joining a social group for Catholics in the heart of the city. He found solace and strength in his new-found faith. “[N]o doubt about it,” he wrote. “I was in a quiet way a happier, more glad-to-be-living sort of person now.” By the time he felt he was strong enough to return to Canada in the summer of 1959, he had a new passion: God.

And he was extremely passionate about it. Obsessed, even. Twice, he made a pilgrimage to the miraculous shrine at Lourdes — and to the Holy Land, too. In his autobiography, he spends page after page laying out his “proof” for the existence of God. And he shares the story how his faith enabled him to resist masturbating, a battle he’d been losing for years. (“I made charts, I gave myself rewards, I went for brisk walks, I recited vows. I even tried tying a kerchief over my eyes when having a bath…”) He said his new idol was a Communist double-agent who found God and then let himself get arrested by Soviet authorities in order to convert them too. And Kurelek looked back on an incident during his trip to Mexico with a new awe. He was convinced that while he was sleeping under a bridge in the desert, he had been visited and saved by a vision of Christ himself.

Now, as he returned to Toronto, Kurelek was certain that his tremendous talent was a God-given gift and that his own suffering was a Christ-like trial. In his autobiography, he openly wonders if he might be a saint.

Just a few months later, he was discovered. It happened that autumn, while he was living in the Annex. An actor friend of his happened to be appearing in a play with the wife of a man by the name of Avram Isaacs. Isaacs was one of the most influential gallery owners in the country; he threw his weight behind the early careers of groundbreaking Canadian artists like Michael Snow (the guy who did the geese inside the Eaton’s Centre and the sports fans on the side of the SkyDome). Word got back to Isaacs that there was an artist in Toronto who “painted like Bosch.” He found it hard to believe — and, besides, he was best-known for supporting abstract work — but he came to the Annex to see for himself. As the actor friend described it, “A skeptical Av Isaacs entered the house, took one sweeping glance around, and said, ‘My God.'”

Kurelek’s first show was held the very next spring. Isaacs displayed about 20 of Kurelek’s pieces at his Greenwich Art Gallery on Bay Street. It was the beginning of a long and wildly successful partnership; Kurelek would go on to have countless shows at the new Isaacs Gallery on Yonge Street (just north of Bloor). People absolutely adored his paintings of Canadian scenes. There were Ukrainian weddings on the Prairies. Kids having snowballs fights. Lumberjacks alone in the woods. Soon, Kurelek was one of the most famous artists in the country. He was asked to publish books, to make endless prints of his work, to give lectures. His paintings were acquired by the National Gallery, the AGO, MOMA, the Smithsonian and even the Parliament Buildings, where years earlier he’d slept outside in the bushes on his way back from Mexico. He was embraced by pop culture, too: Van Halen used The Maze as the cover of one of their albums.

But Kurelek never did fit in. One writer friend described the scene at that first show on Bay Street: “Bill looked terribly out of place at his own opening. He wouldn’t hold a wine glass. The paintings stuck out like sore thumbs. Bill stuck out too. He had a reddish complexion and looked like a lumberjack; he looked as if he were in the wrong country, the wrong century, the wrong situation. It didn’t look as if he had produced the work!”

And it was about more than just his social skills. Kurelek had a new mission that didn’t fit in with the Toronto art scene of the 1960s. He didn’t just want to become rich and famous, he wanted to save the world. And to save it for God.

Along with his Canadian scenes and his disturbing inner-nightmares, Kurelek had started painting what he called “religious propaganda.” His most ambitious work was a series of 160 paintings illustrating the Passion of Christ. He started working on it that New Year’s Eve; it took him three years to finish. (It was finally shown at the St. Vladimir Institute on Spadina near Harbord. Today, it’s the centrepiece of the collection at the Niagara Falls Art Gallery.) And his Passion was only the beginning. Kurelek painted countless religious scenes, including an entire book called A Northern Nativity. It shows the birth of Christ as if it had happened in Canada: in an igloo, by a haystack on the Prairies, in a snow-swept cabin, at a soup kitchen, in a fishing boat.

When the CN Tower was being built, Kurelek even asked if he could pay to have a metal plaque installed on the spire: “O Supreme Builder of the Universe, help us not to make the mistake of the first tower which you confounded.”

The offer was declined. As you might expect, not everyone liked this version of Kurelek. And it didn’t help that much of his work was angry and moralizing. Determined to show people the error of their modern, secular ways, many of his religious paintings combined his Canadian scenes with the kind of horrifying visions he’d painted back in England. On one canvas, he shows a farmer-Satan harvesting souls on the Yonge Street Strip. On another, he paints buckets full of aborted fetuses along a snowy Highland Creek. He gained a reputation for being “a missionary in paint.” One editor called him “a fire-breathing preacher in the old style”. His biographer, Morley, agreed: “Kurelek could thunder like an Old Testament preacher or a modern Savonarola.”

As far as Kurelek was concerned, he had to. The fate of the world was at stake. Even now, as a middle aged man with a successful career and a new family (he met his wife at the Catholic Information Centre at Bathurst and Bloor; they got married at Our Lady of Perpetual Help on St. Clair East), he still hadn’t escaped his demons. He slid back into depression, and made another attempt on his life. His wife stumbled in on him just as he was slashing his wrists. He survived — and it was the last time he tried to kill himself — but it wasn’t the end of his dark thoughts. They stayed with him for the rest of his life. And they got even darker. He became convinced the world was about to end.

This, after all, was the 1960s. The Cold War was in full swing; even the most reasonable, secular thinkers thought the world might end. Schoolchildren were being taught to hide under their desks. The government was building bunkers. They even displayed a model fallout shelter on the lawn in front of Queen’s Park, encouraging private citizens to build their own. In 1962, the Cuban Missile Crisis nearly proved them right.

Kurelek saw all of this through a devoutly religious lens. He was sure God was going to rain fire down upon the world as a form of punishment. A nuclear war, he told the press, was “pretty well inevitable.” But that wasn’t necessarily a bad thing. It would help cleanse the world of sin. “A large part of the human race will die,” he admitted. “With the modern, largely urban way of life destroyed or drastically crippled…” But eventually, it would lead to a better world. “I foresee a new golden age of Faith after intense suffering has purged us of our materialistic pride.”

The key, of course, would be to survive long enough to build that new, utopian, Christian world. So in the late 1960s, Kurelek began to build his own bomb shelter. He was living in the east end of Toronto by then, on Balsalm Avenue in the Beaches. It’s the scene of one of his most famous paintings: in Balsalm Avenue After Heavy Snowfall, the neighbourhood has come alive to dig out after a big storm. Children play in the snow, neighbours wave to each other, some push a car up the street. It’s exactly the kind of quaint Canadiana that Kurelek had become famous for. But all the while, the darkness lurked. Soon, he assumed, the street would be the scene of a much greater calamity.

At first, he planned on putting the bunker in his own basement studio. But the plans soon expanded; he wanted to build an elaborate shelter separated from the rest of the house. It would be fully equipped, with a TV, air conditioning and room for 30 people — a relatively comfortable place to wait for the apocalypse to pass.

By then, though, the bomb shelter fad had already started to fade. Kurelek was the first person in Toronto to apply for a permit in five years. When he tried to get permission to build, the City gave him trouble. His neighbours opposed the plan. His family wasn’t too thrilled about it either. But whatever people said, Kurelek pressed on. When his priest tried to talk him out of it, he looked for a second opinion until he found one that confirmed his own. He was determined to be ready when the bomb dropped.

He defended his views in a letter to friends. “We must concentrate on being personally prepared at all times,” he argued. “This is one reason (though not the only one) why I practice periodic fasts, why I try to do without sleep or with little, under various conditions. This is why I have taken up gardening, because once we do reach an uncontaminated area we will have to grow our own food. This is also why I believe our family vacations should now be camping rather than cottaging… We should deliberately learn to do without things we take for granted, e.g. stoves, insect repellants, a roof over one’s head, regular sleep, vitamins and medicines, packaged foods.”

In the end, though, it seems like the costs were just too much. It would take thousands of dollars to build his shelter. And even for an artist as successful as William Kurelek, that kind of money wasn’t always easy to come by. He bartered and traded for some of the work. Eventually, he’d build part of his bunker on some land up north. But in Toronto, the only physical evidence of the plans for his fallout shelter would be the big, fireproof door to his basement studio.

His apocalyptic vision is, however, still on full display in his paintings. In This Is The Nemesis, he shows the city of Hamilton blown apart by a nuclear explosion, with another blast in the distance where Toronto used to stand. In many of his works, mushroom clouds bloom on the horizons of prairie fields. And in Harvest of Our Mere Humanism Years, a bomb dangles precariously from a thread, hanging like the sword of Damocles above Toronto’s new City Hall.

It may, sadly, have been the long hours Kurelek spent painting those visions that killed him in the end. His basement studio was already a bunker of sorts. There were no windows. There was no ventilation. He worked with toxic spray paint that clogged the air — and his lungs. His doctor warned him to stop, but Kurelek was always stubborn about things like that. The paint, they say, may very well have caused the cancer that ate away at his liver.

The end of his life wasn’t all bad: he was in pain, but he had his family and friends to comfort him. He’d recently returned from a trip to Ukraine, to the ancestral farmlands of his father, a voyage he had longed to make for years. But in those final days, he was still haunted by nightmares and visions. With just a few days left to live, he confided in his priest.

What he saw, he said, was Toronto in flames.

A version of this post originally appeared on the The Toronto Dreams Project Historical Ephemera Blog. You can find more images, sources, links and related stories there.