Editor’s note: This is the fifth post in a series by students at the John H. Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape, and Design. Each piece features an idea for an architectural intervention that would to better connect Torontonians with their ravine system. The designs in this series were created as part of Professor Brigitte Shim’s Thesis Research Option Studio or final Thesis Studio. The work and text in this post is by Nora Barbu, whose bio you can find below.

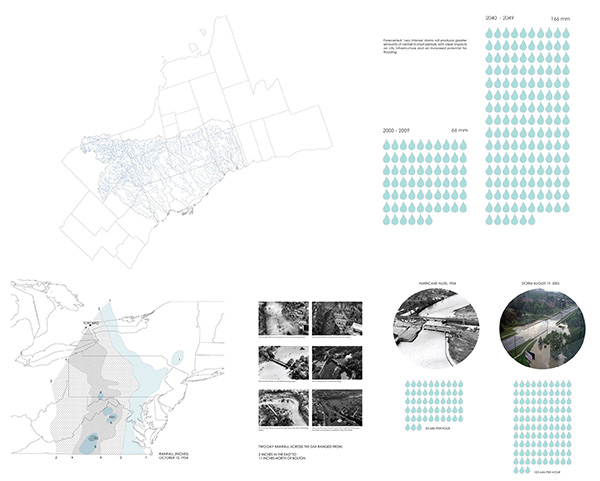

Water creates a dynamic relationship between the land and its settlers. After Hurricane Hazel in 1954, efforts were made to provide structural and non structural approaches to flood control. Today, as downtown Toronto remains prone to flooding, and rainfall forecasts intensify, researching and designing for the floodplains and rising river levels in the Don Valley is necessary. What do we build on the water’s edge in the city’s ravine? Is Toronto prepared for another hundred year storm? This project encapsulates architecture driven by environmental change.

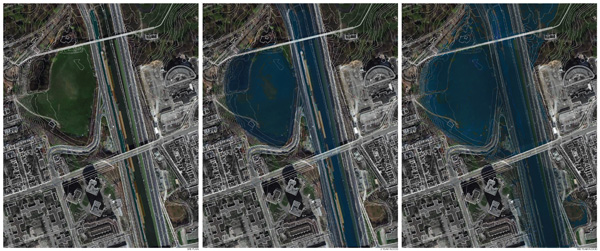

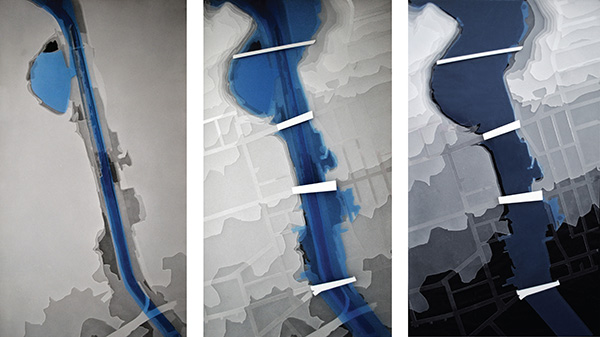

The graph above shows the vulnerability of the city’s major transportation routes in the Don Valley: the Don Valley Parkway and the bridges that cross it. During the “one hundred year flood,” multiple bridges would be submerged or within close proximity to the flood line.

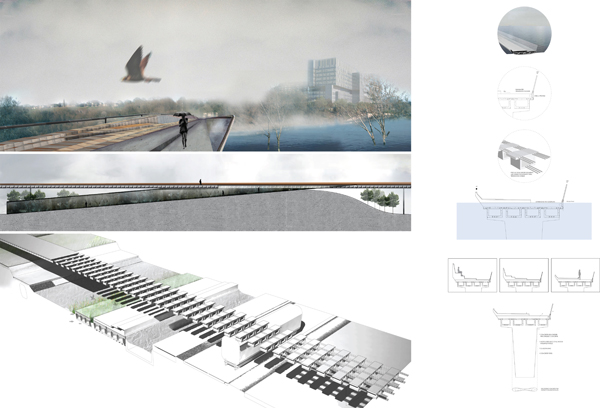

This project focuses on two major axes: a north-south axis that runs along the Don River, and an east-west axis consisting of four bridges. The bridges at Riverdale Park, Gerrard Street, and Eastern Avenue provide nodes for vertical circulation: steps at each bridge allow commuters to enter the flood plain. The main design proposal for this project centres on the pedestrian bridge at Riverdale Park.

Considering the pressure of flood debris and ice flows on bridges and piers, the structural design of the Riverdale Park pedestrian bridge needs to withstand flooding impact. Small cracks in the materials can jeopardize their integrity. The design employs prestressed concrete, which combines the tensile strength of steel and concrete’s resistance to compression. Precast box girder segments are linked together by steel tensioning cables. Additionally, to address the dangers presented by such flows, each pier has an aerodynamic shape that diverts water and debris instead of allowing it to pile up at its base, placing lateral stress on the bridge. The lower step of the bridge stores flood water to illustrate the experience of entering the floodplain.

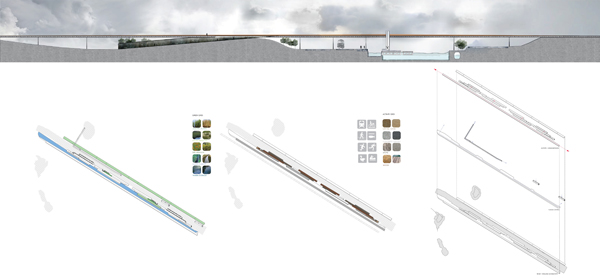

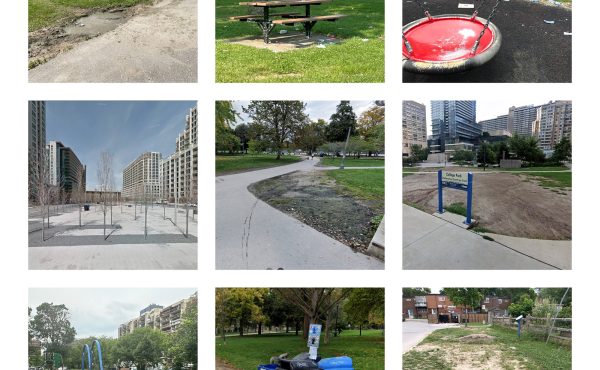

This project also explored a short term flood control plan for the Don River that aids smaller floods (one or two year floods), which led to the question: Can rising water levels become a positive phenomenon?

Water management on the site is divided into three categories: areas for retention, areas intended to be temporarily flooded, and areas which will not be flooded.

By creating a high water channel, lowering an area of the floodplain, deepening the river bed, and creating temporary water storage, the river is given more room to overflow. Buoyant platforms interweave elements of nature, materiality, and urban activity into a unified, heterogeneous infrastructure.

Nora Barbu received a Master of Architecture from the John H. Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape and Design at the University of Toronto. She earned an Honours B.A. at the same institution, with a double major in Architecture and Visual Studies. Her academic research focuses on the interplay of art, architecture and landscape, and pursues designs that fit their social, aesthetic and ecological environments. Daniels Faculty member, Professor Brigitte Shim was her thesis advisor for her Thesis Research Option Studio in the Winter of 2013.

Earlier posts in this series:

- Between the Ravine and the City by Sonia Ramundi

- Beyond the Big Box by Federica Piccone

- Rain to River: Storm Water Infrastructure for the People by Kristen Duimering

- Finding the Ravine: Gateway to Toronto’s Urban Edges by Jason van der Burg