The Stadocentre, Metrodome, Astrodome, and Tower Dome: Toronto historically has had no lack of imagination when it comes to dreaming up gleaming, state-of-the-art municipal stadiums. Yet for more than six decades, the goal of building a multi-purpose sports venue in Toronto seemed frustratingly elusive. Grand 1920s colosseums, modernist arenas, even a stadium with a giant fabric roof were conceived only to be rejected or superseded by grander ideas.

With the Toronto Blue Jays preparing to begin their 26th season under the retractable roof of the Rogers Centre, here’s a look back at Toronto’s long history of dashed stadium dreams.

The idea of a downtown sports stadium first surfaced in the years after the first world war. The trauma of the conflict combined with the city’s ambitions for expansion inspired an organization called the Sportsmen’s Patriotic League to lobby for a 16,000-seat municipal stadium on reclaimed waterfront land between Strachan and Bathurst, roughly where Coronation Park is located today.

The $220,000 War Memorial Staidum would, according to League spokesman Patrick J. Mulqueen, help “rehabilitate the greatest of all Canadian assets, its manhood.”

Plans drawn up by architecture firm Chapman, Oxley & Bishop envisioned a grand neoclassical colosseum with seating around an oval field. The shape lent itself to range of athletic uses, including baseball, football, soccer. Bathurst streetcars would service the main entrance and there was to be ample parking.

The idea had the support of the city, but the expense was rejected in a January 1923 referendum. The design of the stadium, particularly its grand arcaded entrance, didn’t die so easily. Chapman, Oxley & Bishop were later asked to renovate the lakefront field of the Toronto Maple Leafs baseball team, and the company reworked several of their ideas into that design, which was completed in 1926.

It wasn’t until after the second world war that idea of a municipal stadium was earnestly pursued again. Hungry for a major league ball club, maybe even the Olympics, maps were drawn up showing a variety of possible stadium sites, including Riverdale Park, the Don Valley,Thorncliffe Race Track, (old) Woodbine Race Track at Kingston Rd. and Queen, and a former clay pit turned garbage dump on Greenwood Ave.

The Riverdale Park stadium—a replica of California’s Rose Bowl dubbed the “Maple Bowl” by Controller Joseph Cornish—was rejected due to drainage issues and lack of public transit connections. Before long the stadium idea had returned to the back burner.

Then in 1959, in an attempt to land the 1968 Olympics, the idea of a 100,000-seater stadium was floated—literally—south of of the Exhibition Grounds. Based on the design of the Melbourne Cricket Ground in Australia, the expansion of which was central to Australia’s successful bid for the 1956 Games, the $10 million bowl would have been located in the lake roughly where Ontario Place is today.

The designs were permanently shelved when the International Olympic Committee awarded the games to Mexico City instead.

Despite the setback, Toronto’s city fathers were still hungry for stadium. Exploratory committees were formed at the municipal level and pitches were made to Major League Baseball, either for a team in the planned Continental League or an expansion franchise in either the American or National league.

Rather than set up shop north of the border, the American League added the Los Angeles Angels and Washington Senators (now Texas Rangers.) Another set back.

Over the next decade, stadiums were dreamt up in Rosedale and Downsview, where a $100 million complex on the site of the former air force base was pitched by developer Al Chapman, but all went nowhere.

A copy of the Houston Astrodome, the world’s first domed stadium and “Eighth Wonder of the World,” was considered as part of a planned redevelopment of the downtown railway lands but, as Mike Filey writes in his book Like No Other in the World, the first public meeting ended in a shouting match: “Not a nickel of taxpayers’ money for sports,” people shouted.

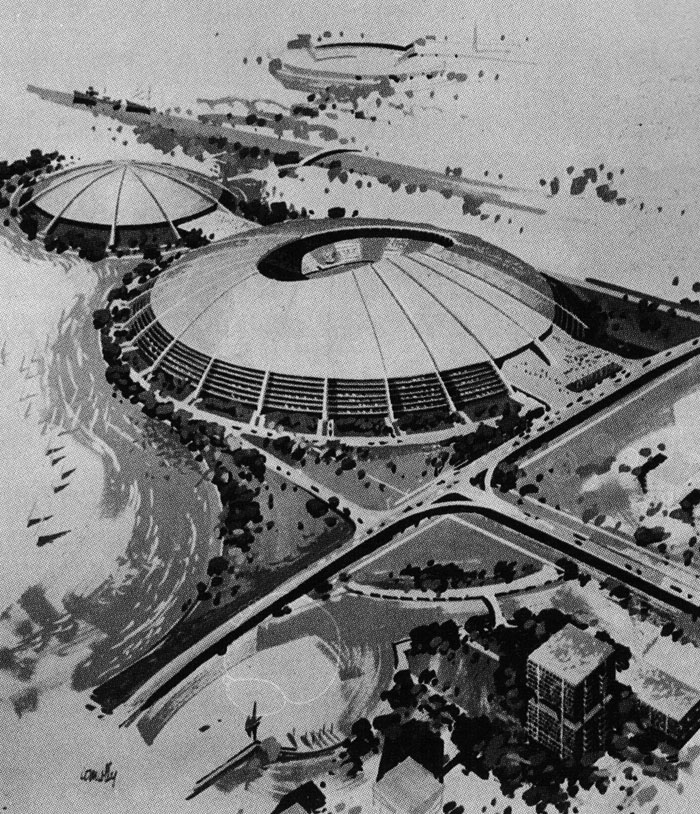

Undeterred by the IOC’s decision to grant Mexico City the 1968 games, Toronto this time prepared to make a push for the 1976 event. Central to the pitch was a pair of domed facilities on the waterfront near the CNE, but it was Montreal that ended up with the games and the grand stadium—the infamous and long-troubled “Big O” (or maybe the “Big Owe.”)

In 1969, at Downsview, North York Mayor Jim Service lobbyied for a circular municipal stadium on the federally-owned former airport lands. Following a visit to Houston’s famed ballpark in 1969, Service believed that a Downsview facility might lure a NFL franchise north of the border. Even the Maple Leafs expressed an interest in quitting the Gardens for the planned dome, hotel, and convention centre. But again, the plans stalled.

It would take the rain-soaked 1982 Grey Cup game at the Exhibition Stadium to truly get the “Metrodome” project rolling. As an ice-cold deluge soaked all but a lucky few of the 32,000 spectators, including Metro Toronto Chair Paul Godfrey and Ontario Premier William Davis, the concession stands ran out of hot drinks, washrooms overflowed, and fights erupted in the stands. It was clear Toronto needed a covered stadium—and fast.

A special provincial committee was formed to sniff out viable sites. Early proposals included the Trillium Dome, a covered arena at the centre of a 3,000-acre development at Highway 401 and Hurontario St. in Mississauga, and a third Downsview stadium, this one with a retractable roof.

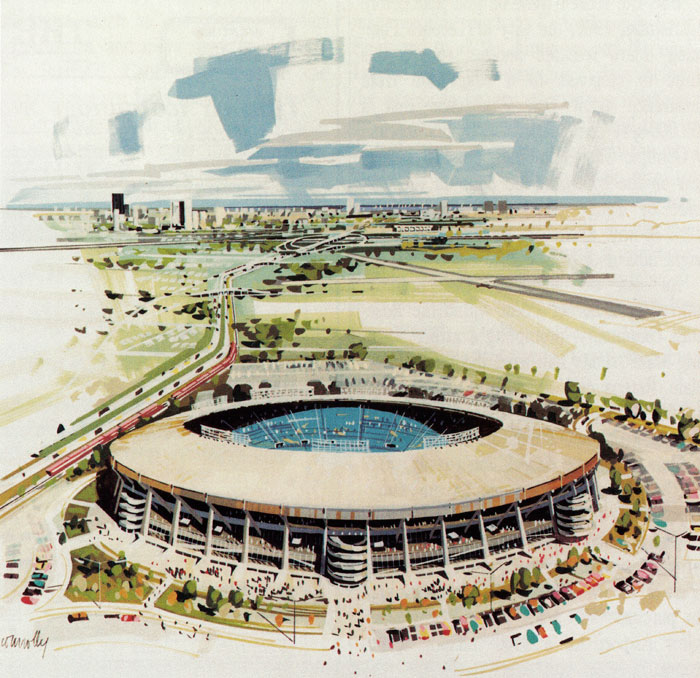

The idea of a stadium that could be both indoor and outdoor depending on the weather appeared to stick, even if the Downsview location did not. When the Canadian National Railway announced plans for an arena on surplus downtown land adjacent to the CN Tower in 1984, the company’s mock-ups showed a field covering that could be stowed in good weather.

The province liked CN’s proposed stadium and its folding roof and hammered out a financing deal with CN, Toronto, and a slew of private companies, including Coca-Cola, McDonalds, and CIBC, who got exclusive access to SkyBoxes and concession rights.

(Interestingly, Mike Filey recalls media consultant Charlie Cipolla suggested that coin-operated Pac Man machines be installed around Toronto as a possible way to raise cash for the Dome. The games would pay out instant cash prizes and enter players into a lottery draw. The idea didn’t make it beyond the proposal stage.)

The design of the roof was put out to tender, and a four viable proposals were received: one opened and closed like the shutter of a camera, another retracted like a sliding door. The winner, designed by architect Rod Robbie and submitted by developer EllisDon, consisted of four separate pieces that would spin and slide into place.

The SkyDome opened on June 3, 1989, more than sixty years after Toronto first dreamed of a downtown municipal stadium. It cost $600 million, but now when rainclouds loom, all it takes is the push of a button to close out the weather. No more ice cold showers.

Mark Osbaldeston’s Unbuilt Toronto 2 has perhaps the wisest words about the SkyDome/Rogers Centre from Blue Jays President and CEO Paul Beeston:

“Is it Camden Yards or PNC Park? No. Does it have the history of Fenway Park or Wrigley Field? No. But it’s ours, the roof works, we start our games at 7:07 at 1:07 and we play every day we’re supposed to play.”

Note: An earlier version of this story stated that the baseball arena in the Riverdale Park photo was Maple Leaf Stadium. It is, in fact, Chicago’s Wrigley Field.

3 comments

The Riverdale Park “rendering” isn’t Maple Leaf Stadium. It’s Wrigley Field, with an earlier version of the outfield bleachers — sometime after 1927 (when the upper deck was built) and late 1930s (when outfield was reconfigured).

the blue jays starting playing in the Rogers Centre (fka Skydome) in 1989. Wouldn’t that make this the 26th season (and not the 21st) at this stadium

A minor correction to give credit where it is due: although Rod Robbie was the design architect and driving force behind the winning SkyDome design, it was actually Michael Allen (from the Ottawa based structural engineering firm, ADJELEIAN ALLEN RUBELI) who designed the retractable roof.

I began working for Robbie Sane Architects soon after SkyDome’s construction was completed. Although the two men worked very closely together for years on that project and together they patented that roof design and several variations, Rod was always quick to make sure that Michael got the credit for coming up with the solution for a retractable roof that would utilize existing mechanical technologies and building materials yet function well in Toronto’s climate extremes. (It’s a classic example of something that appears simple yet no one had ever thought of it before; it’s actually very complex.)

My memory is a bit fuzzy but I believe Michael had his Eureka! moment on a flight between Ottawa and Toronto, then roughly sketched it out for Rod in a King St W restaurant on a napkin which they kept and eventually had framed.