In the most recent issue of Spacing, I wrote about how the idea of “slow zones” is being overtaken by universal speed reductions in cities in Europe and North America. Toronto had been slow on the uptake with both of these ideas, but this spring City Council has been faced with a variety of speed reduction approaches all at once.

Both ideas are attempts to reduce the speed of vehicles travelling in the city in order to improve safety, since slower speeds result in fewer collisions with pedestrians and cyclists, and fewer serious injuries and deaths. In “slow zones,” a defined neighbourhood is designated to have a lower speed limit, generally accompanied by infrastructure changes to encourage slower speeds. With universal speed limit reductions, on the other hand, the default speed limit is reduced across an entire city (or borough) all at once.

The speed limit reductions are generally from 40 km/hr to 30 km/hr (20 mph) on local streets, and from default 50 km/hr to default 40 km/hr (25 mph) on arterial roads unless otherwise signed.

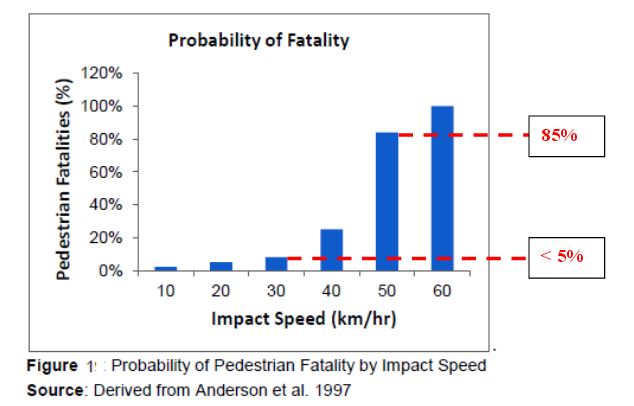

Chart from Toronto Public Health report, “Road to Health: Improving Walking and Cycling in Toronto”

Chart from Toronto Public Health report, “Road to Health: Improving Walking and Cycling in Toronto”

The theory behind “slow zones” is that vehicles tend to drive at a street’s “design speed” — that is, the speed the street is built for. In this theory, reducing speed limits without changing the street’s infrastructure will make little difference. On the other hand, the theory behind universal reductions is that drivers will internalize the speed limit if it’s universal within a jurisdiction. Indeed, a study of a universal speed reduction initiative in Columbia, Missouri showed that it did, in fact, reduce driver speeds (PDF) (although the reduction varied by location).

In Toronto, a piecemeal “design speed” approach has traditionally meant that streets needed to get speed bumps in order to reduce their speeds to 30 km/hr. Earlier this month, City Council passed a new bylaw that specifies conditions where a local street’s speed limit can be lowered to 30 km/hr without infrastructure changes. However, the conditions still operate on the “design speed” principle — only streets where vehicles are already likely to go slow because of the street’s existing characteristics are eligible.

The conditions (PDF) require, first, a local petition in favour of the speed reduction — similar to the “slow zone” approach, which generally demands neighbourhoods specifically request the designation. If certain other basic standards are also met, streets that specifically include school areas, or contra-flow bike lanes, can now get this speed reduction.

There’s also a section for other streets (“Warrant D”), but the conditions are so absurdly complicated that it’s doubtful any street in Toronto would meet them. A street would have to meet THREE of the following four criteria:

- No sidewalk

- Cars parked on both sides of the street (or one side of an extremely narrow street)

- TWO curves that are dangerous to take at more than 30 km/hr, within 200 meters of each other

- Lack of safe stopping distance at TWO locations

(Walk Toronto (PDF) argued to the Public Works and Infrastructure Committee that any one of these conditions should be enough to allow a speed limit change).

However, this bureaucratic tangle is being rapidly overtaken by other developments. The Toronto and East York Community Council is expected to consider in June a report requested last year about establishing a universal 30 km/hr speed limit on local roads within its jurisdiction. There could be implementation complications, but given the plethora of speed limit signs, on what seems like every block in the city (there are 2 on my dead-end block), the relevant ones could simply be replaced. (The Montreal borough of Outremont recently implemented a similar universal speed limit reduction). The result would be more coherent than street-by-street changes. It would still mean different rules in different parts of Toronto, however.

Meanwhile, the province of Ontario is considering giving cities the ability to reduce their default arterial road speed limits to 40 km/hr from 50 km/hr (roads signed at higher speeds would remain unchanged). This initiative follows New York City’s recent move to get New York State to reduce the city’s default speed limit to 25 mph. As part of this month’s motion, Toronto City Council gave Transportation Services the go-ahead to examine the implications for Toronto.

Finally, the Public Works and Infrastructure Committee has also put in motion a “Road Safety Plan for Toronto.” It is partially inspired by the “Vision Zero” initiatives originating in Sweden and now being implemented in New York and elsewhere, which generally include speed limit reductions of one kind or another.

This rather chaotic situation, with multiple, sometimes contradictory initiatives happening all at once, is a reflection of the fact that a lot of the momentum for these speed limit reductions is coming from individual voters, and individual councillors. In New York City, both slow zones and the universal speed reduction were led in part from the top by mayors and city staff, partially in response to lobbying by well-organized groups like Transportation Alternatives. In Toronto, however, City staff have not taken the lead on these issues, nor has a mayor — it has been individual councillors responding to what they hear from their own local voters, to specific tragedies that get media attention, or to what they see happening in other cities.

As I wrote in the print edition of Spacing, a key advantage of universal reductions is equity. When individual neighbourhoods have to take the initiative, most often it is neighbourhoods of single-family homes — usually well-off ones — who are best able to organize. Neighbourhoods with more renters, or new Canadians, are more likely to be left behind. Equally, many people, more often low-income, live on arterial roads, and these are the ones that are most dangerous. Universal speed reductions will benefit a lot more people, more equally.

Universal reductions can always be followed by specific infrastructure measures. Already, in a positive move, Transportion Services has reduced lane sizes and curb radii standards, which will discourage speeding as these are gradually implemented with re-striping and road reconstruction. Traffic light cycles can be adjusted. A toolkit of additional speed-reducing infrastructure changes can be created, to be implemented where speed problems persist.

As with everything in Toronto politics, the process will be messy, but it seems that, one way or another, more and more streets will get slower speed limits. The question really is how many, and how quickly it happens.

5 comments

I suppose the NY default speed limit would be 25 miles/h rather than 25 km/h?

It is about time, reducing the speed limit of downtown area’s local roads would be a great start. I do not care what that limit would be for suburb. If residents in the burb prefers higher speed limit in their neighbourhoods, that is totally fine, none of my business.

NYC speed typo corrected.

This is all a waste of good air. There is little to no enforcement of present speed limits on residential streets. Why bother?

I think the difference between the 30 km/hr initiative and the Road Safety Plan for Toronto is night and day. The speed limit is fine as a notional idea and something that politicians can point to as dealing with a problem, but if drivers don’t voluntarily observe it the effect is practically zero. The Road Safety Plan is a real attempt to study the problem and propose city-wide solutions that would have a real, observable and positive effect on road safety if it was implemented. The problem – much as I hate to agree with Denzil Minnan-Wong, he’s absolutely correct that our Transportation Services department doesn’t have the capacity to do this. What’s required is a re-think of where road safety ranks in the city’s priorities and the allocation of $$$ to study the problem and come up with solutions. Vision Zero has reduced traffic fatalities by over 50% in Sweden but they were already ahead of us even before that plan was introduced.

Let’s not bring in 30 km/hr speed limits and think we’ve solved the problem – that would be the first, small step in what’s needed to make real change happen.

I would really prefer a different view of how to reduce excessive speed and create smoother flow, to the benefit of both pedestrians and drivers.

I think that the tendency in Toronto is to stick in endless stop signs and traffic lights and speed humps which tends to result in my experience is frustrated drivers speeding between signs and humps in an attempt to make up time lost to same.

The desire is not stop-rapid accelerate-rapid brake- repeat.

The desire is somewhat slower speeds, more consistently and predictably, resulting in little discernible lost travel time for drivers, but much safer conditions for other users of the road.

On side streets in particular, I think a focus has to be on reducing the right-of-way, which in suburban areas can be upwards of 11M. Something closer to 7M would be more appropriate, possibly 8m if parking is permitted on one side.

Reducing widths could also allow for tree-line boulevards on some streets that now lack these.

There is also a need to address how far set-back homes are on some streets, as this leads to a ‘perception’ of greater width/sight lines and desire for speed.

**

On the subject of major roads I would argue the principle problems tend to occur on roads with greater than 4 lanes as this creates much longer crossing distances which are more difficult to navigate as a pedestrian and create much more distraction in the field-of-view for drivers.

However, one must be realistic, where we tend to see such roads, ie. the major E-W streets in Scarborough, those roads tend to be about 2km apart, with no effective through streets in the intermediate space.

To consider making Lawrence or Ellesmere 4-lanes again (down from 6) you need a new E-W road in between them, not necessarily any larger than one lane each way, plus turning lanes, but traversing most or all of the territory of the larger roads in parallel, and offering traffic an alternate route. Such new roads might also offer an easy design alternative for new bike lanes and for more pedestrian-amenable neighbourhoods.

On one hand, the above could be quite pricey, and given the need for various other infrastructure investments, such as transit, its hard to advocate for them.

Yet, in many cases there are existing streets that could form a significant part of such routes, and the expense, phased over time, might be quite manageable, and a fairly cost-efficient way of improving safety and reducing congestion, while also unlocking some land value too.