Nothing epitomizes space age urbanism quite like the revolving restaurant.

Imagine sitting at the top of a modern skyscraper, the lights of the city twinkling below, enjoying a rib eye steak or prawn cocktail served in a wine glass. In the background, there’s light piano music and the faint clink of cutlery over hushed conversation. Out the window, a civilized world of traffic-free highways, supersonic air travel, and missions to the moon drifts gently by.

For a brief time in the late 1970s, Toronto had three revolving restaurants, making it particularly well endowed with futuristic dining options. Today, just one remains, and the concept is firmly out of fashion.

The earliest concept for an elevated, moving dining room can be traced to an unbuilt design prepared for the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair. That year, industrial designer Norman Bel Geddes proposed a restaurant shaped like a dumbbell turned on its side. Cars would park in the base and the restaurant would be perched atop a giant elevator column. Had it been built, guests would have enjoyed panoramic views of the exhibition grounds from the spiral-shaped upper levels.

The first realized revolving restaurant opened a little over 25 years later in Dortmund, Germany. The 209-metre Florianturm, which opened to the public in 1959, was primarily a communications mast, but shrewd designers included several public features in an effort to spin the concrete column as a tourist attraction, much like Canadian National did with the CN Tower.

The idea quickly spread to other cities. A tower inside the Ala Moana mall in Honolulu, Hawaii sprouted in 1961 and the famous “Eye of the Needle” atop the Space Needle in Seattle opened for the 1964 World’s Fair. It was this restaurant that captured the public imagination, at least in the U.S.. Elvis dined there in “It Happened at the World’s Fair,” and queues were routinely hours long.

Toronto’s first flirtation with a revolving restaurant concept surfaced a few years later, in 1966, with North York’s plan to reverse engineer a downtown.

A roughly 300-metre telecommunications tower was conceived as part of a massive Yonge St. development proposal that was to include a new city hall, apartments, hotels, and theatres. Mayor James Service was particularly enthusiastic about the tower; he hoped it would attract TV and radio stations as tenants.

Murray Chusid, the chair of the North York property committee, wasn’t convinced, however. In 1968, he worried that the tower would remain “pie in the sky.”

“If it’s pie in the sky then he’ll be eating it in the sky, in the revolving restaurant on the tower,” Service said.

As it happened, it would take until 1972 for Toronto to get its first revolving restaurant. The principal attraction of the Holiday Inn-Downtown on Chestnut St. was a 27th-floor panoramic lounge called “La Ronde.” It boasted views of City Hall, Nathan Phillips Square, and the midtown skyline. The room could seat 200 and included a stationary cocktail lounge, dance, and music hall.

“You’ll turn on a stunning new perspective of the city as you enjoy the fine food, wine and attentive service,” advertisement copy promised.

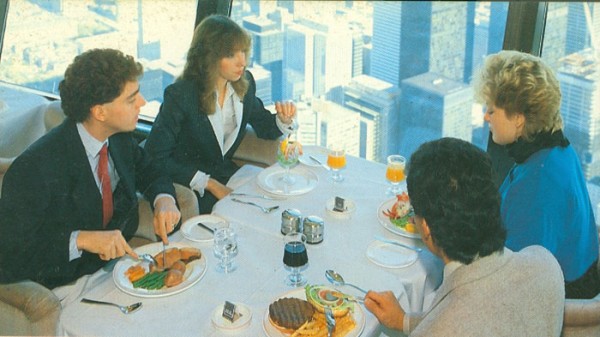

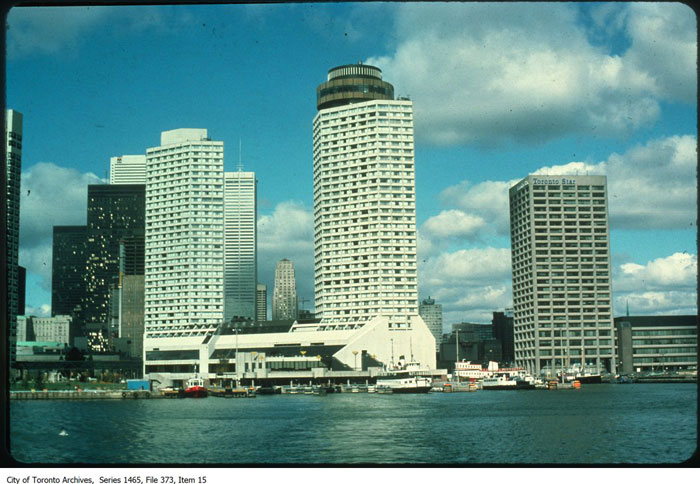

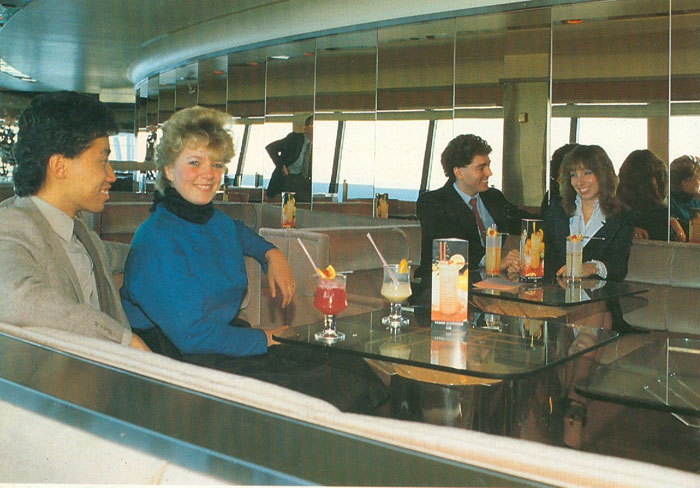

A year later, Ottawa-based developer Campeau Corp. promised the city’s second rotating eatery atop the Harbour Castle hotel at the foot of Yonge St. When it opened in 1975, the Lighthouse, a two-storey, disc-shaped rooftop addition to the roof of the luxury waterfront hotel, trumped La Ronde for height and size. The dining room was spread over two floors and was accessible by a glass-walled elevator that ran on the outside of the south tower. A full revolution took roughly an hour.

The Harbour Castle became a Hilton in 1977, partly due to the fact the 960-room luxury hotel had been steadily losing money since it opened. Campeau blamed stiff competition and a drop in convention business for backing out of the hotel they had built just two years earlier. Today, operating under the Westin brand, the Harbour Castle’s revolving restaurant level is stationary.

The last active restaurant of its kind in the city is also the newest. At 351 metres above the city, the 400-seat Top of Toronto restaurant in the main pod of the CN Tower sat the equivalent of 115 storeys above the ground.

The extreme altitude did little to boost the restaurant’s popularity, however. A scathing review in the Globe and Mail ripped into the bland styling and low-quality food.

“The restaurant feels about as space age as a golf club lounge.” journalist Joanne Kates wrote. “It feels like a mile-high womb.”

“It has been designed to be cosy and comfy so that guests would never feel overwhelmed by the sky-high enormity of it all. Which is, of course, a neat way of avoiding capitalizing on the very thing that is most exciting about the place.”

The food, she wrote, was “pleasant” but underwhelming and expensive. Perhaps the reason was due to the CN Tower’s stringent fire safety rules, which required food to be cooked at ground level and bussed up in an elevator, making the tower the largest dumbwaiter on the planet. Diners turned their noses up, and the tower struggled to attract visitors in its early years.

(In 1982, the original decor was captured in the movie Highpoint, starring Christopher Plummer. The picture received mixed reviews, but it became famous for stuntman Dar Robinson’s astonishing leap from the CN Tower—the highest stunt fall in movie history to date.)

CN Tower 360 Restaurant gun attack by Retrontario

In 1984, the Top of Toronto was given an art deco-style makeover and attendance began to climb. In 1995, it was renamed “360” and in 1997 a new, 9,000-bottle wine room was marketed as the highest cellar on the planet.

Like the city’s observation decks, of which there were once several, the CN Tower was likely responsible for killing its competition. 360 is three times taller than Toula, the Harbour Castle’s rooftop offering, and the Holiday Inn on Chestnut St. has since been converted into a University of Toronto student residence.

Who knew marketing a restaurant in the clouds could be such a tall order?