The bodies of the children were buried under the cellar floor.

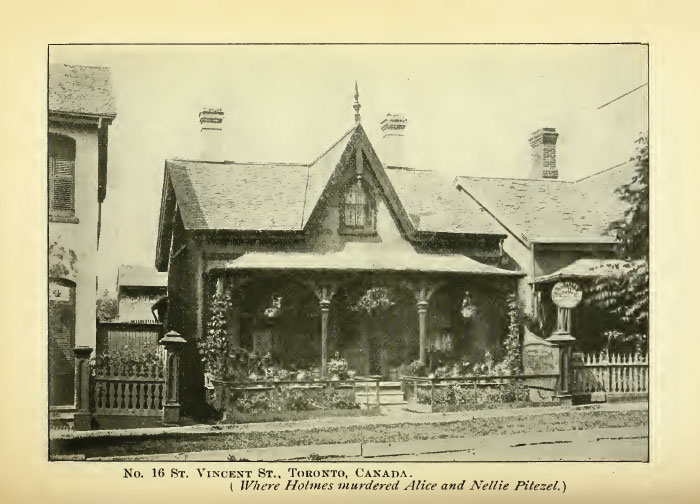

In a gloomy crawlspace beneath the home at 16 St. Vincent St. near Yonge and College, police detective Frank Geyer of Philadelphia pushed his shovel through a patch of soft soil. The stench that burst from the ground was overpowering.

With the help of Alf Cuddy, a detective from Toronto, Geyer continued down further.

“The deeper we dug, the more horrible the odour became,” Geyer would later write. “When we reached the depth of three feet, we discovered what appeared to be the bone of the forearm of a human being.”

Both immediately knew they had found. In a picturesque little two-storey cottage set a few feet back from the sidewalk, the search for the elusive final victims of America’s most notorious serial killer had finally ended.

It was July 15, 1895.

The bodies of Alice and Nellie Pitezel had been placed on top of each other. 13-year-old Alice was the deepest. Her body was on its side, her hands facing west. Nellie, aged 11, was face down, her head pointed south and her dark plaited hair draped across her back.

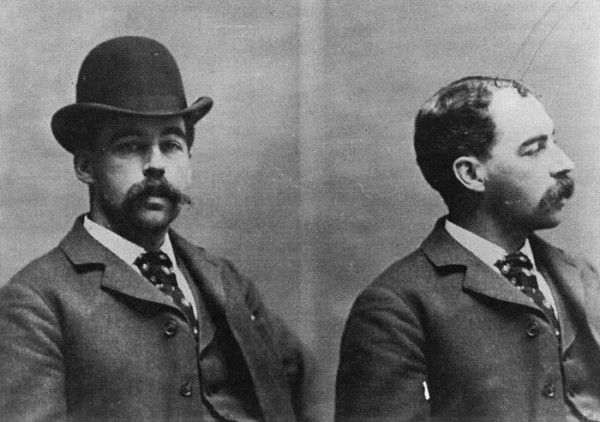

They were the daughters of Benjamin Pitezel, a close associate of Herman Webster Mudgett.

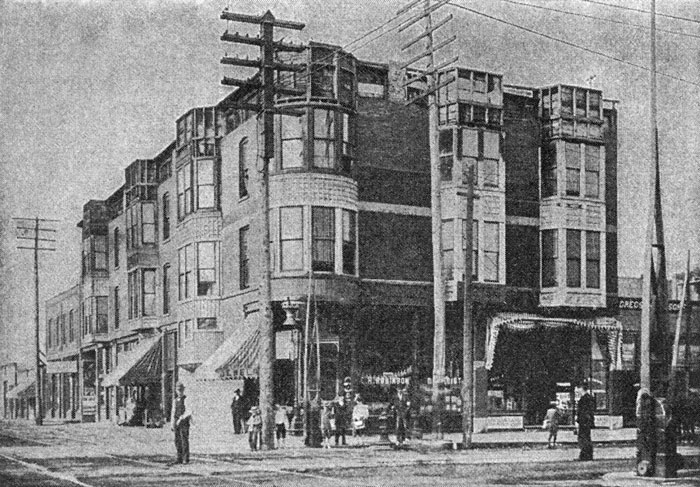

Born in New Hampshire, Mudgett was trained as a doctor and operated as a pharmacist in Englewood, Chicago. In the 1890s, he built a massive wood-framed hotel near the future site of the World’s Columbian Exposition, a World’s Fair held in Illinois to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’ arrival in the New World.

The massive six-month event drew some 27 million visitors and was a critical moment in the increasingly powerful and confident country’s history. It featured the world’s first Ferris Wheel, among other wonders of the age.

Holmes’ cavernous hotel, which was known locally as the Castle, was full of unspeakable horrors. Some rooms had doors that could only be opened from the outside, others could be filled with gas to poison the occupant. A metal vault in the basement suffocated anyone lured inside.

The owner’s access to chloroform and other sedatives made many of the murders criminally easy.

Some of the bodies were burnt, others were dissolved in quicklime. On several occasions, Holmes sold the skeletons to medial schools. His victims were sometimes guests at the hotel, sometimes his own employees, but they were almost always young women.

The Globe would later call him “a wolf in human shape.”

In 1893, Holmes devised a life insurance scam with Benjamin Pitezel, a carpenter and close associate who had helped build the Castle. The pair took out a $10,000 policy with the Fidelity Mutual Life Association and planned to fake Pitezel’s death and claim the money.

Instead, Holmes really did kill Pitezel and made the death scene look accidental. He convinced his former colleague’s widow, Carrie, to let him take three of their children—Alice, Nellie, and nine-year-old Howard—to London, England, where their father was supposedly hiding out.

The trip would be long and ultimately tragic.

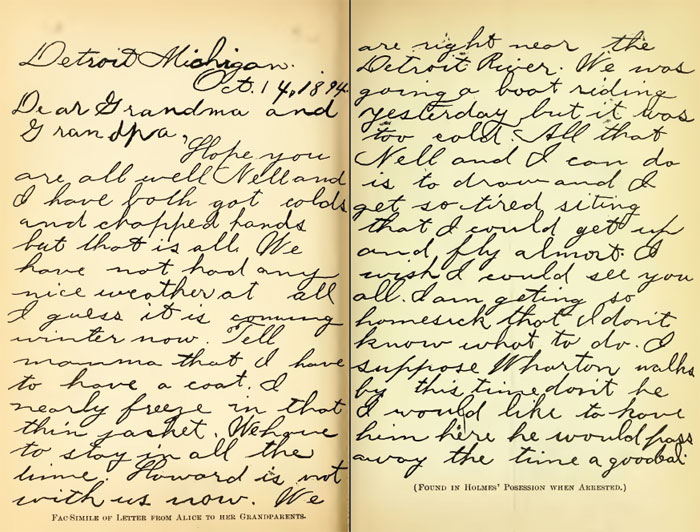

Both Alice and Nellie wrote letters to their mother as they moved across the United States, but none ever reached home. Holmes collected them in a box marked “Property of H. H. Holmes,” author Erik Larson recalls in his book, The Devil in the White City.

Meanwhile, the Fidelity corporation had grown suspicious of the Pitezel insurance claim and sent a private detective to apprehend Holmes. He was found alone in Boston, where he confessed to the fraud and was transported to a jail in Philadelphia. There was no sign of the children, save for their unsent letters.

Six months after Holmes had taken Alice, Nellie, and Howard, Det. Frank Geyer was dispatched to find them. He didn’t hold out much hope of finding them alive. From his cell, Holmes steadfastly claimed they were with a woman named Minnie Williams en route to their father.

The case would have personal significance for Geyer. Just months earlier, his wife, Martha, and daughter, Esther, had died in a house fire.

Using hotel registration books and geographical references in the letters, Geyer followed the trail to Cincinnati and then to Indianapolis. As he traveled, the extent of Holmes’ manipulation began to unfold. At one point, he had been moving the children, Carrie, and Georgiana Yoke, his young wife, around the country separately via different hotels.

As Larson writes, in Detroit Alice and Nellie were just blocks from their mother without being made aware of it. In one of Alice’s letters from that city, she noted, ominously, that “Howard is not with us now.”

In July, the search bought Geyer to Toronto, where he was paired with local detective Alf Cuddy. Together they checked hotel guest books and showed real estate agents photos of the children. 120 years ago this week, they got a break.

After days of intense media attention, Geyer and Cuddy got a tip from Toronto resident Thomas Ryves, who said Holmes matched the description of a man who had briefly rented the house next to his on St. Vincent St.

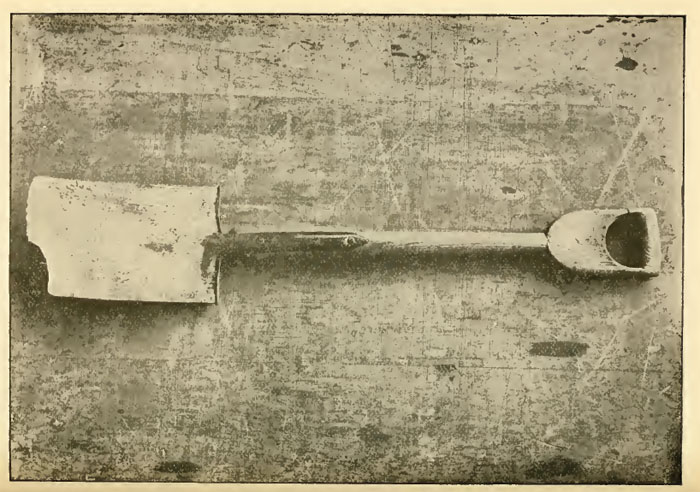

Ryves said the man had arrived with little furniture and borrowed a shovel to dig a hole in the basement for the storage of potatoes. Armed with the same shovel, Geyer and Cuddy made their first exploratory turns of the soil in the basement where they would find the bodies of Alice and Nellie.

The detectives became sure of the identify of the decomposed remains when the son of the current tenant of 16 St. Vincent St. produced a toy egg he had found while moving in. It was made of wood and inside was a toy snake that sprung out when the egg was opened. It matched a description of a toy the girls’ mother had provided.

The home owner also reported finding partially burnt girls clothing stuffed inside the chimney.

The basement was extensively excavated, but no trace was found of Howard, the final missing child.

Geyer had long suspected the boy had been murdered earlier and buried in Indianapolis, and that assertion would ultimately be proven correct. The burnt remains of Howard, a few pieces of jaw, some teeth, and a mass of organs, were found in the flue of a chimney of a property Holmes had rented. Again, it was a toy found in the house that helped police identify the young victim.

Meanwhile, police began searching Holmes’ Englewood hotel, where they found countless bones: ribs, hips, a scapula, and vertebrae. Several of the complete skeletons Holmes had sold were also tracked down.

It will never be known how many people Holmes killed, though the number may be in excess of 200. He was convicted of the first degree murders of Benjamin, Alice, Nellie, and Howard, and six counts of attempted murder. During his trial, Holmes testified how he had locked the girls in a trunk and left for dinner, returning “at [his] leisure” several hours later to kill them by forcing gas into their prison.

He was hanged on May 7, 1896, and buried at Holy Cross Cemetery in Philadelphia.

To deter grave robbers, Holmes’ coffin was encased in 10 feet of cement.

The Toronto Evening Star called the case “one of the strangest stories of a life of crime and remorseless cruelty that the continent has produced.”

“It is not possible to find in the annals of criminal jurisprudence, a more deliberate and cold-blooded villain than [Holmes,]” wrote Det. Geyer in an 1896 book detailing the case.

Today, the home and St. Vincent St. are gone. The residential road became part of Terauley, then Bay St. in the early 1900s. Were the building still standing, it would be at roughly 852 Bay, where there’s a condo tower and bagel shop.

One comment

The little girls are buried in Saint James’ Cemetery, Toronto, just north of the entrance. There is no marker.