The Gardiner East Follies returns for yet another extended run at City Hall beginning on Tuesday morning, when city officials present three scenarios for relocating the highway’s eastern end to free up valuable waterfront land.

For much of this year, and some of 2014, the lion’s share of public, policy and political attention has focused intensively on the stretch between Cherry Street and the Don River. (For more on the origins of the problematic loop, read this.)

First Gulf, which wants to transform the sprawling Lever Brothers site into Toronto’s Canary Wharf, has a strong interest in the alignment of the Gardiner/DVP interchange, as do the developers who own land along the Keating Channel. In a show last spring, suburban councillors pushed to keep the highway network in tact, while downtowners fought to replace that one portion with an at-grade boulevard.

After council backed the hybrid option, staff spent the summer consulting with waterfront activists, developers and engineers to figure out how to pull the Gardiner north towards the railway yard while re-conceptualizing the interchange as a set of ramps between two highways instead of a single continuous route.

The arm-waving about the interchange, however, has meant that almost no one is paying attention to that nasty segment of the Gardiner that runs astride Lakeshore Blvd East, between Jarvis and Cherry. Indeed, the latest city staff report notes that the section west of Cherry “will largely be maintained.”

And therein lies a massive missed opportunity, according to architect and planner Calvin Brook.

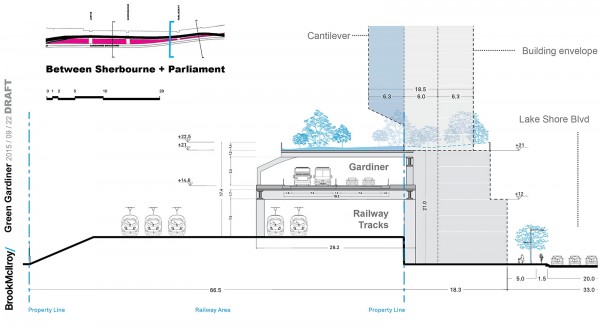

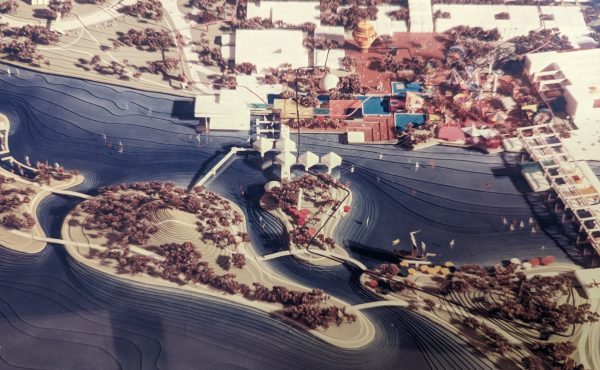

His firm, Brook McIlroy, has pitched city staff on an ambitious scheme to stack that stretch of the Gardiner above an expanded rail corridor as a means of creating a kilometre-long elevated linear park, 3.3 hectares of new developable city land and a fresh lease on life for Lakeshore Blvd East.

The plan [download it from DropBox] will be presented briefly during tomorrow’s committee meeting; city officials are sufficiently interested that they’ve commissioned a cost-benefit evaluation. Brook McIlroy’s consultants, meanwhile, estimate that the capital outlay for that new Gardiner segment will be $316 million — an amount that would be offset by land sales on 4.3 million sq.-ft of freed-up space.

Brook, who has been pondering how to unstack the Gardiner and the Lakeshore for many years, explained his proposal to Spacing last week.

Metrolinx, he says, plans to expand its GO service from 400 trains per day to over 1,000 as the agency moves to an electrified regional rail offering over the next 15 years. That means adding tracks through the Union Station corridor, and therefore widening the railway berm that has long been implicated in the waterfront’s poor accessibility. The city owns a long finger of land south of the tracks between Jarvis and Cherry, as well as the land beneath the Gardiner and the Lakeshore; the three slices are almost 70 metres across in some places.

If the City and Metrolinx can align their construction agendas, Brook says, they could expand the existing berm south to create not only additional track space, but a deck above the new tracks, upon which the four-lane Gardiner could run. The highway portion, in turn, could also be decked, creating a linear park overhead.

“The premise of this is very simple,” he states. “It’s to take two interruptions in the fabric of the city and turn them into one.”

Brooks points to several compelling arguments in favour of re-building the eastern Gardiner in this way:

- Staging: the construction of the berm, the rail lines, the decking, the highway and the green roof could all be undertaken without making any alterations to the existing Gardiner. That translates into no construction delays and additional costs related to staging, which can significantly drive up capital outlays. When the new Gardiner is finished, traffic can be re-routed onto it, and the demolition of the old one can commence.

- Unlocking city-owned land. By stacking the Gardiner on top of those new rail lines, the city frees up a stretch of land that’s about 40 metres deep and almost a kilometre long – more than enough space, Brook says, to develop point towers, mid-rise buildings and other structures along the north side of Lakeshore Blvd. East

- Public space improvements. With new development now possible along the north side of Lakeshore, that street gains a second lease on life, and can be transformed into an urban avenue rather than a surface highway. Likewise, the linear park built above the decked Gardiner will serve the residents of those buildings developed north of Lakeshore, as well as other waterfront visitors and inhabitants. It also provides opportunities to create mid-block connections and even wider land bridges across the tracks that would link the East Bayfront community to St. Lawrence.

Brook points out that the linear park will be roughly at the same vertical elevation as the deck of the current Gardiner, so this extended structure won’t serve as yet another visual barrier. “What’s really important is that it’s very porous in a north-south direction,” he says, with easy pedestrian/cyclist access between Lakeshore, the linear park and gateway points on the other side of the corridor.

He also observes that Brookfield Oxford, the Canadian commercial development giant, has deployed new decking technology at its sprawling Hudson Yards project in mid-town Manhattan, allowing an active commuter rail yard to continue functioning while a massive intensification project is constructed directly above it.

The idea requires both political will, but also a leap of faith — not because it is technically complex or financially outrageous, but rather due to the fact that Toronto, with its incrementalist political culture, has long tended to shun big moves.

Yet the railway berm, constructed back in the 1920s to modernize access to an industrializing waterfront, was a big move, as was the construction of the Gardiner in the mid-1950s. Big moves, one could argue, must be met with other big moves. And that’s what Brook will be proposing tomorrow.

With the Gardiner East EA due to be submitted to the province by next spring, municipal and provincial politicians should listen to Brook because his idea is not only plausible; it has the potential to be transformational in a highly challenged geography that requires us, finally, to make no (more) little plans.

17 comments

A brilliant, grand scale and innovative idea. Meaning it will never see the light of day in small minded, complacent, bickering Toronto.

Intriguing. I assume that part of this construction would be an opportunity to build a streetcar portal beneath the railway tracks at Cherry, to eventually extend those tracks south into the Port Lands?

I do appreciate the time and though put into these initiatives.

However with driver-less cars/transportation in the next twenty years I somehow get the feeling, that if built, it would be like all the bell phone jacks in my house (Kinda useless).

Bringing Cherry tracks south of the rail corridor needs to be done at the earliest opportunity (when Queens Quay & Cherry junction realigned). To link it to a project of this scale, the odds of which being realised are at best distant, merely adds to the excuse list to not get it (and East Bayfront LRT, and Commissioners track to link both to the Leslie Barns) done.

I see a giant wall being created in this scheme. This is a case of misguided incrementalism. The only true solution that nobody has political will and/or money to implement is burying both the railway and the highway. It has done wonder for Barcelona – why does Toronto deserve anything less?

Brilliant! Should also look at the Transbay Terminal project in San Francisco as an example of a stacked corridor:

http://transbaycenter.org/uploads/gallery/transit-center-architecture/cross-section-caltrain-north.jpg

http://transbaycenter.org/uploads/gallery/transit-center-architecture/ttc_31.jpg

It seems that people keep forgetting that we need ramps to and from the elevated Gardiner. Where will those go in this scheme? Do people just choose to ignore the research shown to us by the study team? It shows that people use this section of the Gardiner to get to and from the downtown. That means we need connections with ramps. It’s not just a bypass. This is a wonderful idea if you didn’t need huge amounts of space for access ramps. How would ramps to and from the westbound lanes work? Would they come from Esplanade if they are on the north side of the rail corridor? Go down to the Gardiner and you will see just how much space those ramps take up.

Staging is huge. Most of this can be built while the current highway and rail corridor are unaffected. That greatly reduces the wasted costs to temporarily satisfy commuters.

The Gardiner would be at a lower elevation with this, meaning the on/off ramps are less intrusive. It seems obvious that the underground Gardiner will never be feasible. It is also quite obvious that the solution lies in using the space above the rail tracks. A few years back there was the “Gardiner Waterfront Viaduct” plan which was also above the tracks.

It appears the math on this was $300M for construction and $16M in property tax revenue – a 20 year return.

@Mike, it’s not about deserts. Of course nobody deserves less–or more–than Barcelona, but that’s a big red herring.

I don’t understand the point in the article about north-south porousness though. Climbing up five or six storeys to get to a green deck, and then down again on the other side, doesn’t sound like an easy crossing.

Also how do ramps work?

First, lose the “green deck”. A linear park is not needed at such height and way too expensive. If desired, land bridges can be created in selected places with north-south pedestrian connections. Also, north-south pedestrian walkways can be created going under the gardiner, like the new one in Southcore. This scheme will not work west of Yonge because so many buildings just south of the rail corridor, so the highway would have to end at Yonge, and someone traveling through would need to rejoin the Gardiner west by traveling south on Yonge.

The boulevard option is still the best value, if money needs to be spent to improve travel time then fix the spadina on-ramp where it always gets clogged. Why add a lane of traffic to the gardiner and then remove it at spadina. there is a jam of people trying to get on and off in the same stretch. Put the money into smoothing that out by letting people off the gardiner for an exit and then add them AFTER.

“First, lose the “green deck”. A linear park is not needed at such height and way too expensive.”

Except that one of the biggest issues with the current highway is all of the salt we pour on it during the winter which destroys the structure… if we cover it we won’t need to pour nearly as much salt on it and should save HUGE money on the maintenance side.

I realize it may be south of the Downtown Relief Line study area, but I wonder if this proposal would provide an opportunity to use the same stacked right-of-way for a portion of the westward leg of a new line connecting Yonge and the Danforth.

Finally, a far reaching idea that solves many problems in one go. If only Toronto had the ambition and wherewithal to see it through! It: 1.) Significantly improves traffic staging during construction (although it may impact GO train staging); 2) removes a major barrier to the waterfront (the highway AND the tracks); 3) Gets rid of the elevated portion from Lakeshore, enabling it to become a great urban realm. I’m all in for this!

Brook isn’t the first one to imagine putting the Gardiner on top of the rail corridor. It has been looked at several times (including during the latest round of Hybrid modifications), but the biggest impediment has always been the radius of the ramp needed to connect the Gardiner to the DVP. It simply doesn’t work.

John

Why is the City only discussing the east Gardiner? A long term vision and master plan is needed for the entire Gardiner X to provide a real solution for transportation connectivity, constructibility and financing.

Please call and we will explain our proposal presented recently at the Toronto of the Future

exposition.

JFS_II – I don’t see why the connection between the DVP and the Gardiner couldn’t be done with a bit of imagination. Why couldn’t the whole curve could be rebuilt further north, maintaining essentially the same radius? It would have to cross the Don at a shallower angle, but should be doable.

Marek – I agree. To a casual observer it must seem almost criminal that High Park reaches south to within a short distance of the lake – its natural southern edge, but terminates prematurely, in part due to the Gardiner. Access to the water could put it in a whole different league of large urban parks. Other Gardiner-related crimes abound.