Tulips, windmills, and all those salacious, smoke-filled thoughts aside, Amsterdam is internationally regarded as a haven for urbanism and as a hub for design and technology. I recently had the pleasure of spending several months living in and exploring the Dutch capital and was continuously surprised at how history and innovation collide to create one of the world’s most interesting cities. Based on my travels, I’ve compiled a list of the top five features of urbanism in Amsterdam to perhaps shed light on some areas where Toronto could learn a few things by going Dutch.

Embrace the bicycle

As someone who is notoriously scared of cycling in Toronto, the fact that I spent everyday on my bike alongside those seasoned Amsterdammers must mean the city’s infrastructure planners got a few things right. The city is largely flat and compact with many narrow streets, and it would be easy to say that just based on its geography Amsterdam fits better with cycling than Toronto ever could. However, it’s thanks to committed political protest, years of investment, and a delicate mix of public pressure and political decisions, that Amsterdam became one of the most bike-friendly cities in the world. Most recently in Toronto, new fines have been introduced for drivers passing cyclists too closely as well as an increased fine for opening a car door on a cyclist. Hopefully, these developments, along with the roll out of more separated bicycle lanes in the city core, will get me and other cautious cyclists out on bikes soon.

Temporary urbanism keeps a city lively

Amsterdam is a city that seems to be constantly reinventing itself and one of the things which reinforces this perception is the trend of pop-ups. While pop-up shops and restaurants appear in cities all over the world, in my short time in Amsterdam I couldn’t help but notice how fast events or business ventures come and go. Fuelled by the Internet and a culture enthralled by social media, the trend of temporary spaces creates the sense of an ever-evolving and fast-paced environment and forges a vibrant city from cultural and economic perspectives. Even as I was heading back to Toronto, a pop-up beach was being constructed right in front of the central train station, in one of the city’s busiest districts. The trend is so alive in Amsterdam that its spawned its own cultural festival dubbed Pop Up Week Amsterdam. Although Toronto dabbles with pop-ups in the form of markets, restaurants, and shops, the sheer number and magnitude of this urban trend in Amsterdam leaves much to be desired here at home.

Height restrictions create an intimate city

Perhaps one of the most visible differences between Toronto and Amsterdam in terms of the built environment is the lack of high rises in this Dutch capital city. The proximity of Schipol airport and the historic city centre impose strict height restrictions, which means no high-rises, at least for the city centre. In fact, the question to construct high-rise buildings in Amsterdam is the subjected of quite a heated public debate and it’s almost comical how sensitive Amsterdammers are to buildings that are more than four stories high. There are pockets of Amsterdam, outside the core, where high-rise developments are springing up fast, a phenomenon well known to every Torontonian. While many cities, Amsterdam and Toronto included, are pressed for space and expecting more inhabitants to come as the decades roll on, greater densities become a fact of necessity and the question of high-rises development will continue to be a prickly subject for this low living city.

Preserve and re-purpose

Like many European cities, Amsterdam has a rich history which is reflected in its architecture. Recognized as a UNESCO heritage site, Amsterdam’s Canal District dates back to 17th century and features homogenous rows of narrow, gabled houses with iconic facades that have become synonymous with the city itself. For contemporary Amsterdam however, the city’s history and a desire to preserve its visual integrity has created limitations on changing the city’s built form. This in effect has fuelled a culture of innovation and re-purposing of space, with many historic buildings being retrofitted with modern design elements to house the needs of the 21st century city. Meanwhile, to the dismay of many citizens in Toronto, there has often been an underwhelming sense of urgency to protect historical buildings. It’s only quite recently that architects and planners are taking bolder steps to protect heritage sites and incorporate them into new building designs.

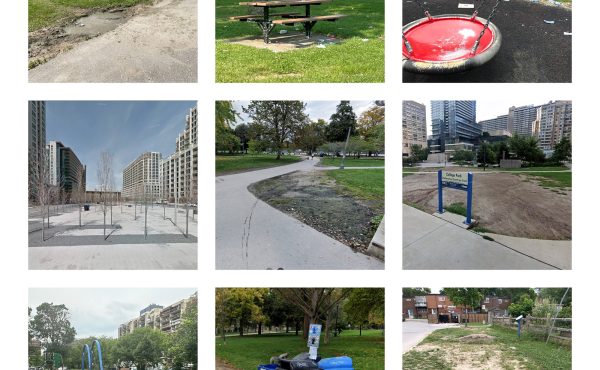

Spend more time on the streets

Square footage is scarce in Amsterdam, and despite smaller apartments its residents have adapted ways to maximize on urban space. One of the most fascinating features of city life in Amsterdam for me, was seeing how the city’s residents are not shy about using public spaces. It wasn’t uncommon to see people set up a table and sit on the street outside their front door to enjoy a family dinner or bring out stools to the side of a canal. For many residents, public parks also act as an extension of their living spaces, which becomes very clear on those rare warm and sunny days. It seems as though in Toronto, people are much more reserved when it comes to occupying space outside, opting for private patios or backyards instead. It was refreshing to see people making the most out of what limited space there is in Amsterdam, because it gave off the feeling that the city’s residents really feel a sense of ownership over the streets and public spaces.

Katerina is an urban geography student at the University of Toronto

photos by Veronika Gribanova, Katerina Ryabets, Mariano Mantel, Zapdelight