The bases were loaded. It was the bottom of the eight. This was it: first place was on the line. Toronto and Newark headed into that Saturday afternoon battling for the lead in the International League — along with the team in Jersey City. With only a couple of weeks left in the 1887 season, every win was vitally important. And with only an inning left in their second game of the day, Toronto was losing to Newark by three runs.

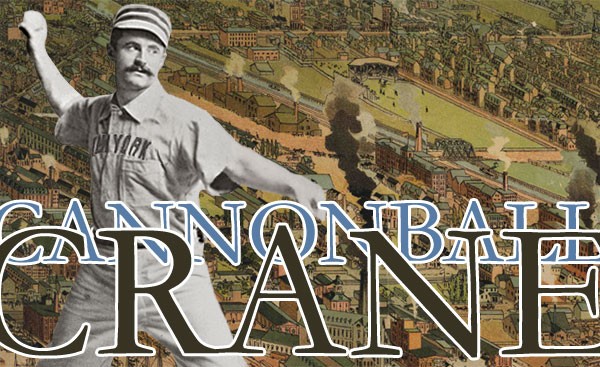

That’s when Ned “Cannonball” Crane came to the plate. He was the ace of the Toronto pitching staff; a giant of a man: big and tall and impossibly strong. He once threw a ball more than 400 feet — a world record; impressive even by today’s standards — and he could throw a ball faster than anybody else could, either. He was one of the game’s first big power pitchers. He combined the blistering speed of his fastball with a “deceptive drop ball” that baffled opposing hitters. It was a deadly combination. He won 33 games for Toronto that year — more than any other pitcher has ever won on any Toronto team.

And he could hit, too. Crane was one of the best hitters in the whole league that year. His .428 average is still considered to be the best batting average by a pitcher in professional baseball history. (If he’d hit that in the Majors, it would put him sixth on the all-time list for any position.) On the days when Crane wasn’t pitching, he was in the outfield or at second base so they could keep his bat in the line-up.

On that Saturday afternoon in September, Crane had already done more than his fair share. Toronto and Newark were playing a double-header — two games at the Torontos’ new stadium at Queen & Broadview, on a spot overlooking the Don Valley.

It was originally known as the Toronto Baseball Grounds, but it would soon be nicknamed Sunlight Park in honour of the nearby Sunlight Soap Works factory. Spectators could walk in off Queen Street or ride up in their carriages and park their horses on the grounds. Admission was a quarter — plus an extra dime or two to sit in the best seats in the house. The sheltered grandstand had enough room for more than 2,000 people, and there was standing room for another 10,000 — a capacity not that much smaller than a Leafs game at the Air Canada Centre today. But the stadium had never seen attendance like this. Those two games against Newark drew a record-setting crowd.

In the first game, Crane pitched all nine innings, keeping the Newark hitters at bay while the Toronto bats smashed their way to victory. The final score was 15-5.

But there was still one more game left to win. And now the Torontos had already used up their ace. The scheduled pitcher for the second game was a fellow by the name of Baker — and as the first pitch drew near, he was out on the field, getting ready just as everyone expected.

And then, a surprise: as the Toronto team took the field to start the second game, Baker didn’t head toward the pitcher’s box. Instead, it was Cannonball Crane who came back to take his spot in the middle of the diamond.

A reporter from the Globe was there: “As soon as it was made clear that Crane was to pitch the second game, hundreds leaped to their feet and cheered frantically, a mighty whirl of enthusiasm took everybody within its embrace and an astounding volume of sound shook the stands and swept down toward the city and out over the grounds like the march of a tornado.”

Cannonball Crane was going to pitch two games in one day.

Still, even with Crane in the pitcher’s box, the second game didn’t get off to a good start. Toronto fell behind and stayed there. It wasn’t until the eighth inning — behind by three runs — that they rallied to load the bases, bringing Cannonball to the plate with a chance to play the hero.

And that’s exactly what he did. The slugger hit a double, clearing the bases. Three runs scored. The game was tied. It would head to extra innings.

Crane kept pitching. He held Newark scoreless in the tenth. And then again in the eleventh. He had now pitched 20 innings in one afternoon.

In the bottom of the eleventh, Crane came to the plate with a chance to play the hero yet again. He crushed a pitch high into the sun above the Don Valley: deep, deeeep, gone. A walk-off home run. Toronto had won both games. According to the Globe, as Crane rounded the bases “the mighty audience arose and cheered and stamped and whistled and smashed hats… the frantic fans dashed on to the field and carried Crane aloft as his foot touched home.”

The team’s owner — a stock broker by the name of E. Strachan Cox — headed over to the scoreboard. He wrote a message for the crowd:

“CITIZENS, ARE YOU CONTENT? TORONTO LEADS THE LEAGUE.”

The team had taken first place — and they would keep it for the rest of the season, winning every single game for the rest of the year. By the time it was all over, they’d won 16 in a row. Toronto had our first baseball championship.

But our hero wouldn’t be back for the 1888 season. Instead, Crane signed with the New York Giants, helping them win the National League pennant and then the World’s Series. He threw a no-hitter that year — and became one of the very first pitchers to ever wear a glove while fielding.

Sadly, that season was the beginning of the end. Things began to unravel for the pitcher almost as soon he left Toronto.

At the end of that first season with the Giants, Crane was invited to join Spalding’s World Tour. The biggest stars in baseball signed up for a trip around the world, showcasing the sport to other countries. They played games in the shadow of the Sphinx, on the grounds of the Crystal Palace in London, outside the Villa Borghese in Rome… plus Australia, New Zealand, Ireland, Scotland, France, Samoa, Yemen, Ceylon…

The problem was that when the players weren’t on the field, they were partying. Crane had gone his entire life without ever having a single drink… right up until the days just before the tour began. “Crane,” as one newspaper reported, “did not know what the taste of liquor was like until he made the trip around the world. He got his start drinking wine at the banquets tendered the American tourists.”

And as Crane quickly discovered, he liked to drink. Far too much.

“Crane began drinking heavily from the moment he joined the tour in Colorado,” according to the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR). “By the time the men reached San Francisco, he had missed several games due to drunkenness and being hung-over.” They hadn’t even left the United States yet and Crane was already a mess.

He spent much of the tour serving as a sluggish umpire with a headache and heatstroke instead of actually playing in the games. At some stops, he never even got off the ship — choosing instead to get drunk on board with his tiny, trouble-making pet monkey, entertaining his fellow passengers by breaking into song. At one point, he even had a stand-off with soldiers at the French-Italian border when they insisted he pay an extra fare for his simian companion.

The Giants repeated as World’s Series champions the very next year. And Crane was back in the pitcher’s box, serving as their ace, winning five games in the Series. He would go on to have a solid Major League career, finishing up with a 3.99 ERA over eight seasons. But as he continued to drink, his weight ballooned and he lost his effectiveness as a pitcher. His final year in the Majors was a disaster: a 6.98 ERA over twelve games. He was released by the Giants twice, signed by Brooklyn and then released by them, too. Things were spiraling out of control.

People in Toronto still loved him, though. In 1895, he returned to play for our city. But he wasn’t the same. After an uninspiring beginning to the season, he was released for what the Toronto Evening Star called “alleged sulkiness on the field.” The team across the lake in Rochester then signed him and gave him another shot, but Crane didn’t even show up for his first game.

He made his final appearance at Sunlight Park in the summer of 1896. He was playing for Springfield now. The Toronto fans gave him a warm welcome as he came out onto the field overlooking the Don Valley, but it was a bittersweet reunion. By then, Crane weighed nearly 300 pounds. His glory days were far behind him. He was no match for the Toronto bats. They crushed him.

Once, as the Globe remembered, Crane’s name “inspired dread among all other players… But that is but a hazy memory. The once mighty name has lost its magic. It no longer inspires dread and fear… He essayed to pitch for Springfield against Toronto over the Don yesterday afternoon, and he made a sorry exhibition of himself… It would be painful to go into the details of the game.” Soon, Springfield gave up on him too.

Finished as a player, Crane tried to find work as an umpire. But even that was a failure. “Crane,” the Globe reported, “is said to be a way off in his judgment on balls and strikes.” The newspapers blamed it on whisky. At 34 years old, he was unemployed and alcoholic, his wife and child had left him, he was depressed.

“Crane sank deeper into the bottle as his prospects and money quickly ran out,” SABR recalls. “He became despondent, freely talking about his troubles and the grim outlook for his future wherever he went.”

Cannonball Crane wouldn’t live to see the end of that 1896 season. On a Saturday in mid-September — almost nine years to the day since his glorious double-header in Toronto — he spent the afternoon getting drunk in his room at the Congress Hall hotel in Rochester. He hadn’t paid his bill in ages. When he went downstairs, the owner warned him that if he didn’t fork over the $70 he owed, he would be forced to give up his room. Crane promised to settle his bill. And then he headed back upstairs.

There was a bottle of chloral waiting for him.

The next morning, the maid couldn’t open the door. A bellboy climbed up to peer through the transom. Crane was laid out on his bed. Dead. The official coroner’s report described it as an accidental overdose. But everyone assumed it was suicide.

The next morning, he was remembered on the front page of the Toronto newspapers. His life had come to a tragic end, but thanks to those two games in the thick of a pennant race one Saturday afternoon in September, Cannonball Crane had written his name into the history of our city. He’d become an indelible part of Toronto sports lore, mentioned over and over again in our newspapers over the course of the next century — remembered fondly for bringing our city our very first baseball championship.

Next summer — in 2016, nearly 130 years since the Torontos won that pennant — a new plaque will be unveiled on the spot where Sunlight Park once stood. It will include a photo of Cannonball Crane, an ace at the height of his powers. The name of our city’s first big baseball star will live in glory on Queen Street once again.

A version of this post originally appeared on the The Toronto Dreams Project Historical Ephemera Blog. You can find more sources, images, links and related stories there.