The very first legendary home run ever hit in Toronto was hit in 1887. More than a century before Joe Carter’s famous World Series walk-off at the SkyDome, Cannonball Crane hit a homer into the sky above the Don Valley to end a game at Sunlight Park. It was made all the more impressive by the fact that it came during extra innings in the second game of a double-header — and that Crane had pitched all 20 innings for the Toronto Baseball Club on that Saturday afternoon. Those two victories sparked a 16-game winning streak that brought Toronto our very first baseball championship.

Cannonball Crane fell apart soon after, spending his final days as a broke, unemployed, depressive alcoholic who met his end by drinking a bottle of a chloral at a seedy motel across the lake in Rochester. But thanks to that home run, he’d already written his name into the history of our city. He was a hero. For decades to come, his name would be mentioned with reverent awe on a regular basis in Toronto. And it still is from time to time. In fact, next summer Heritage Toronto will unveil a new plaque on the spot where Sunlight Park once stood — at Queen & Broadview — and it will include a mention and a photo of Crane. Nearly 130 years after his game-winning home run, the name of Cannonball Crane is still remembered.

Those opportunities for quasi-immortality don’t come along very often. Extraordinary talent has to conspire with a strange amount of luck in front of an unusually large audience. Cannonball Crane was one of the greatest pitchers and sluggers of his time, brought to the plate at just the right moment in front of a record-setting crowd — about 10% of the entire population of Toronto was at Sunlight Park that day.

Last Wednesday night, one of the greatest sluggers of our time came to the plate at the SkyDome during one of the strangest innings in baseball history — and more than 10% of the entire population of Canada was watching.

No one ever expected José Bautista to become a superstar. He was drafted in the 20th round. He spent years as a forgettable utility infielder. In his rookie season, he got released and traded four times in just a few months — from one terrible team to another. Finally, Pittsburgh traded him to Toronto for a middling minor league catcher.

The Blue Jays didn’t expect him to become a superstar either. But after making an adjustment to his swing — adding a higher leg kick to change his timing — that’s exactly what he did become. In 2010, he hit 54 home runs — a dozen more than anybody else hit that year. And he hasn’t looked back. Since Bautista became a slugger, no other slugger has hit more home runs than he has. On Thursday, Joe Posnanski of NBC Sports called Bautista’s career “one of the most bizarre and inspiring stories in the history of baseball.”

They say that thanks to his early struggles — along with having to face the subtle and not-so-subtle racism of the old school baseball establishment — the Dominican Bautista has always played as if he has something to prove. And that, in part, is what makes him such a perfect fit for Toronto.

Torontonians, too, feel like we have something to prove. We always have. It’s our infamous colonial mentality, stretching all the way back to our early days as a muddy outpost on a distant, snowy frontier. Our city was founded as a capital — but a tiny capital, thousands of kilometers away from the heart of the British Empire, dwarfed by the American juggernaut to the south. We’ve always been secretly ambitious (our founder, John Graves Simcoe, wanted Toronto to become a city so awesome that Americans would beg to be let back into the British fold), but we worry that if we’re honest with ourselves we’ll find that we’re largely irrelevant. That inferiority complex was already in place long before Cannonball Crane stepped to the plate on that September afternoon in 1887. It was, I suspect, part of what drove the crowd’s frenzied reaction when he crushed his game-winning home run.

As the fans lifted Crane onto their shoulders and paraded him out of Sunlight Park and onto Queen Street, the team’s owner scrawled a triumphant message on the scoreboard: “CITIZENS, ARE YOU CONTENT? TORONTO LEADS THE LEAGUE.”

The crowd went nuts. In Toronto, we’re always looking for signs that we really do deserve our place as one of the most important cities on the continent — even if those signs come from something as random and trivial as the outcome of a baseball game. On that day, it must have felt like our city was finally coming into its own: a booming metropolis in a brand new nation… and now a famous baseball star to call our own and a fresh championship pennant to hang in our brand new stadium.

It felt like that again in the early 1990s, as Joe Carter wrote his own name into our city’s history with his own game-winning home run. We were still a booming metropolis, even bigger now, playing on a bigger stage, proud of our country and our place in the world — of peacekeeping and of Heritage Minutes and of top spot on U.N. lists — with yet another fresh pennant hanging in yet another brand new baseball stadium. Those Blue Jays seemed like us, the way many in Toronto were beginning to see themselves back then: cosmopolitan, multicultural, professional, elite…

But since then, of course, our sports teams haven’t exactly helped with the whole inferiority complex thing. At this point, no North American city with as many major sports franchises as we have in Toronto has gone this long without at least appearing in a championship final. And while sports are supposed to be a silly distraction that ultimately doesn’t mean much, it does do something to a city — there is a civic toll that comes with being a city full of Leafs fans. Especially here, where sometimes it still feels like we live on a forgotten, snowy frontier, where blowing a 4-1 lead late in a hockey game seems to confirm our worst fears about ourselves and our place in the world. Even if that’s really quite silly.

In Toronto, we’re used to getting our hopes up only to have them immediately dashed in spectacular, heartbreaking fashion. We’re used to feeling embarrassed by our sports teams, and that feeling spills over into other areas, too: we’re embarrassed by our sports teams, by the new name of the SkyDome, by our transit system, by our racist Prime Minster, by our crack-smoking mayor…

For most of the Division Series, it felt like it was all happening again. As far as talent is concerned, the Blue Jays are a juggernaut — some say they’re one of the greatest baseball teams ever assembled. But in a short playoff series bad luck can bring down even the greatest of baseball teams. And Toronto is used to bad luck.

When the Jays lost the first two games at home, there was a familiar sinking feeling. And as they clawed their way back into the series over the next two games, hitting thrilling home runs in the distant heat of Texas, we were reluctant to get our hopes up again, a city full of Charlie Browns sick of trying to kick that football.

For most of that Wednesday night, in the sudden death of Game Five, it seemed like we were right to be suspicious. For the first six-and-a-half innings, disaster loomed: the Jays quickly went down by two runs, fought their way back to tie the game with a mammoth home run from another lovable Dominican slugger — Edwin Encarnación, walker of the parrot, bringer of hat tricks — and then, almost immediately, there was that bizarre fluke throw by Canadian catcher Russell Martin, the ball clanking off Shin-Soo Choo’s bat and sputtering down the line as the go-ahead run dashed home from third base. This was how we were going to end our season? This confusing mess of a run?

The pathetic, childish, dangerous rain of beer cans that followed wasn’t just about that specific moment in the game, it was about 20 years without a Blue Jays playoff appearance, about half a century without a Stanley Cup, about Vince Carter and Chris Bosh and Andrea Bargnani. It was disgust not just with the umpires or the rules, but with all of sports in general, with the whole concept of random chance, with the very nature of the universe itself…

But luck is a funny thing.

Baseball — like life — is at its best when it feels like magic. It’s a long, unfathomably complicated thing, a baseball season. It’s impossible for a mind to wrap itself around all the pieces and interactions involved: the hundreds of players, the thousands of games, the hundreds of thousands of individual plays that can be broken down into millions of distinct elements. It can be an awe-inspiring experience, watching it all unfold. The almost quantum-like fluctuations of individual pitches gradually build themselves into larger structures over the course of the summer, into the baseball equivalent of planets and stars: games, seasons and careers. At times, luck and human agency come together in a sequence of events that seems to defy the laws of reason and logic and chance — producing moments that seem nearly miraculous. Cannonball Crane hits a walk-off home run on a day he pitches 20 innings. Joe Carter becomes the only player in the history of the sport to hit a come-from-behind home run to win the World Series. We are reminded that amazing, wonderful, stupid, lucky things can happen. Even to us.

No one has ever seen anything like that seventh inning. Posnanski called it, “The craziest, silliest, weirdest, wildest, angriest, dumbest and funniest inning in the history of baseball… There has never been an inning like it.” That thought has been echoed over and over again in the days since it happened — not just by people in Toronto, but by baseball fans everywhere. On her CBS Sports Radio show, Amy Lawrence promised, “We will never forget what happened in that seventh inning.” It was, without a doubt, one of the most memorable 53 minutes in the entire history of a sport that has kept records since before the American Civil War… since before Canadian Confederation… since before Toronto’s first skyscraper was so much as a glint in an architect’s eye… Talent and good luck conspired on an international stage in a way that no one has ever seen before. And it happened in Toronto. To Toronto.

Russell Martin tries to throw the ball back to the pitcher and it hits Choo’s bat. The Rangers make three straight errors. José Bautista comes to the plate…

No current Blue Jay has been a Blue Jay as long as José Bautista has. No Blue Jay has waited longer for the team to make the playoffs. For years, Jays fans have worried that bad luck and the lack of talent around him would conspire to waste his years here. That he might be doomed to share the fate of Carlos Delgado and Roy Halladay: superstars who never played a playoff game with a blue bird on their chest, who will always be remembered fondly in Toronto, beloved, but never had a chance to write their name into the history of our city in one instant, with the indelible ink of a miracle in the postseason or during the final days of a pennant race. They never had the chance to do something extraordinary with our whole city watching, our whole country, our whole continent… the kind of moment that turns you into more than just a baseball player, that makes you, in some very small way, immortal.

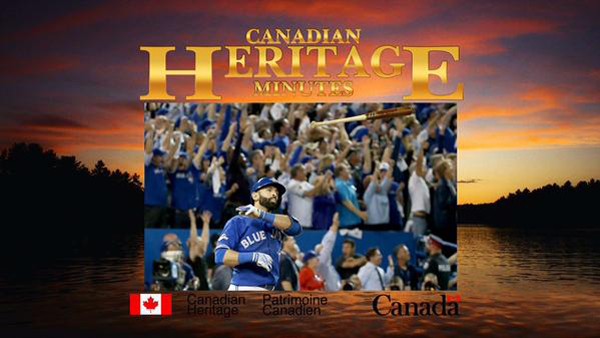

You could see it all in that bat flip. The years of struggle. The years spent playing for Toronto teams that were never quite as good as he was. The years of being ignored in favour of the Red Sox and the Yankees. The years without a playoff berth. Gone. In an instant. In one blazing miracle of a home run.

Gone for Bautista and gone for Toronto, too. We’re happy to have that bat flip speak for all of us — which is part of why I think we fell so deeply and instantaneously in love with it. It’s the swagger Toronto is learning to have. The swagger we want to have. The Toronto of Drake and of #The6ix. Of a giant TORONTO sign in Nathan Phillips Square. Of one of the world’s great music scenes. Of Nuit Blanche and First Thursdays and Friday nights at the ROM. Of a city that is slowly realizing — despite all the real and serious problems we still have to solve — that we really are pretty great, y’know.

We’re a city coming to the realization that more than 200 years after Simcoe founded our muddy town, we actually have lived up to our original promise. And if we still doubt it, Bautista’s home run gives us another chance to get the external validation we want so badly. For this moment at least, we can forget about them flying our flag upside-down and about whatever Harold Reynolds thinks. Toronto, the scribes of NBC Sports remind us as they marvel at that miraculous inning, is “one of the world’s great cities.”

Now, whatever happens, we’ll always remember these Blue Jays. These Jays who feel in so many ways like a reflection of our own city. Of the Toronto of 2015. A cast of characters drawn together from all over the world. Truly multicultural. The young, social media savvy pitcher from Long Island. The rookie closer, the youngest player in baseball, who quit school as a kid to work in the fields of Mexico. The oldest player in baseball, who loves the members of his fan club so much that he goes to their weddings. The quiet Dominican slugger who bought an entire block of his poor, corrupt-sugar-company-run hometown so the residents can still keep living there. The nerdy veteran pitcher from Nashville who has battled depression and struggled with childhood sexual abuse, who mastered the mysterious art of the knuckleball when it seemed like his career was over. The Australian reliever. The Japanese goofball. The Italian-American who spent years playing in the independent leagues before finally getting his big break. The catcher from Montreal who gives press conferences in both official languages. The rookie from Mississauga who runs like the wind. The whiz-kid Canadian General Manager, who got his start with the Expos, who is usually reserved but who parties, gets drunk, and curses with his team on the night they clinch the pennant.

Even if the season ends this week, even if the Jays don’t win another game, people in Toronto — people all over Canada — will remember Donaldson and Tulo and Price and Sanchez and Papa Buehrle and Pillar’s crazy catches and the beaming smile of Ben Revere…

But most of all we’ll remember José Bautista. And that bat flip. And the night it felt like Toronto really could live up to our spot on the big stage. Just like we did in 1993. And in ’92. And in 1887.

A version of this post originally appeared on the The Toronto Dreams Project Historical Ephemera Blog. You can find more sources, images, links and related stories there.

One comment

Wow, Adam. Great writing!