Interview by: Ilana Altman & Melanie Fasche

Bonnie Rubenstein has been a director at the Scotiabank CONTACT Photography Festival since 2002 and is responsible for the festival’s artistic programming. In 2003 Rubenstein established CONTACT’s public installation program and since then has overseen well over 100 projects by both emerging and established artists from Canada and around the world. Each year she curates several high-profile, large-scale installations of photography in public spaces throughout the city, from street billboards and subway platforms to building façades and architectural spaces. In addition, Rubenstein has curated numerous solo and group exhibitions of photo-based works for the festival at major museums and galleries throughout Toronto, some of which have toured internationally.

Bonnie Rubenstein holds a Master of Fine Arts Degree from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and studied Art Education at the Philadelphia College of Art. She has held positions at the Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago. While Special Projects Director at Lisson Gallery, London, UK, she represented international artists and coordinated major public art commissions, exhibitions and publications internationally.

Ilana Altman: The Scotiabank CONTACT Photography Festival is embarking on a major milestone – its twentieth anniversary — how did the festival begin and how has the festival evolved over the last twenty years?

Bonnie Rubenstein: CONTACT was founded in 1996 by four gallerists – Stephen Bulger, Linda Book, Judith Tatar and Darren Alexander. At the time, there were large photo events occurring internationally – Le Mois de la Photo in Montreal, Houston FotoFest, Les Rencontres d’Arles, but few galleries were showing photography in Toronto. They decided to found a festival here as a means to celebrate the medium, educate the public and create an economy for artists. The idea, from the beginning, was that it would be democratic, that anyone could participate. They anticipated having a couple dozen partners presenting exhibitions and events related to photography, and to their surprise there was enormous interest from the beginning. In the first year of the festival, 1997, there were over 50 participating venues.

I started at CONTACT in 2002, three months before the festival was due to open for the year, so it was a tough initiation. Five years into the festival the budget was very limited and there were only two of us working full-time; yet participation had increased dramatically—over 130 venues–so logistically it was quite challenging.

Twenty years on we still maintain the democratic aspect of the festival through our open call to participate, and we will always encourage open exhibitions. It is really important to us to engage the whole community – students, emerging artists, all kinds of people active with the medium and its many different forms, as well as established artists and galleries. In 2004 we added the category of featured exhibitions, which are submissions selected by a jury, based on the quality of the artist’s work, the presentation, and the curatorial concept. In 2006 we co-presented our first major international exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Canadian Art, and since then have continued to develop primary exhibitions at major museums and not-for-profit spaces. This year there are twenty throughout the GTA.

Melanie Fasche: When did the festival begin staging public space installations and why did you consider it important to bring work out of the gallery and into the public realm?

BR: My directive for the 2003 festival was to develop curated exhibition programming and we did not have a gallery at the time, so I initiated the public installation program. I had worked internationally on public art and knew this direction offered many exciting possibilities.

Actually, it was the artist Robyn Collier who planted the seed in my mind about a month after I started at CONTACT. He wanted to present his photographs in the subway, similar to something he had done in Montreal. Instead I asked him to develop a new public project for the 2003 festival, along with three other significant artists, Ken Lum, Jamel Shabazz and Catherine Yass, and then we secured funding from the Canada Council.

It is reported that only about 35% of the population go to galleries, so rather than isolating works in a white cube space, we opted to bring art into the public realm and encourage an interaction with the public and the spaces that surround the work. The images are part of a larger dialogue with people’s day-to-day life, the city, and current events around the world. Photography has the ability to be intensely meaningful in so many different ways, even though we are all now inundated with photography on a daily basis. The fact that personal engagement with the medium is much more pronounced than ever before makes our endeavours to bring photographic works into the public realm all the more relevant.

IA: The medium of photography is so closely associated with advertising. We are used to seeing large-scale images across the city employed for marketing purposes. How has the festival repositioned photography in the public realm?

BR: When we started the public installations we very specifically used traditional advertising spaces; accessible sites that provided a predetermined framework for photographs, and locations where people were accustomed to seeing images. We were essentially removing the ads and replacing them with art. We have since expanded this concept but still use billboards and street level signage. Ultimately the public installations have a dual function. They are artistic projects and, like advertising – only much better–they draw attention to the entire festival.

IA: In 2015 you partnered with StreetARToronto (StART), Waterfront Toronto and Partners In Art to produce and install the Best Beach mural by Sarah Anne Johnson on the Westin Harbour Castle Conference Centre façade. This project represents an exciting new collaborative approach to commissioning, as well as a new approach to durational work. As I understand it, the infrastructure is permanent but the photographs will change on a rotating basis. Can you tell us more about the curatorial vision for this project and the partnership model?

BR: We were approached by StART. They had wanted to do something photographic for a long time. They had also been in discussion for a few years with Partners In Art, who wanted to sponsor a StART project. Part of StART’s mandate is a five-year timeframe for projects, so from the beginning it was intended to be temporary. However, a photographic mural has a shorter lifespan and would likely not last for five years because the colours fade, so it was agreed to rotate the photograph every two to three years.

Lily Zendell and I planned a hunt to find the right venue, and first met with Rebecca Carbin of Waterfront Toronto, whose offices are at the foot of Bay Street. We walked out of the building and saw the enormous blank façade of the Westin Harbour Castle Conference Centre. It immediately seemed ideal but we still went on the tour we planned, and then settled on the first site we saw, it was perfect. That stretch of Bay Street has been called the ugliest block in Toronto. It was so grey and dull—and the mural has certainly transformed its reputation.

Our installations must always articulate a relationship between image and site, and from the beginning we imagined a bold, colourful landscape image that expressed something about the lake and the islands that are beyond what the eye can see. We made a long list of artists, then a shortlist, and Sarah Anne Johnson rose to the top. We knew she would understand what was needed and rise to the challenge. Her mural is spectacular and the community has been extremely supportive.

IA: For CONTACT’s twentieth anniversary you are staging twenty public space installations throughout the city. Each installation is a marriage between site and content and therefore, each project is quite unique. What is your approach to siting the installations?

BR: Sometimes the site comes first, sometimes the work, the projects develop in a variety of ways. When I see work that seems ideal for public display, at times I immediately know where to position it. Other times we have to search long and hard to find the right site. We now have many annual sites that we return to and it can take months to find the right work for a particular site. Either way, there has to be a strong connection between the content of the work and its context, whether socially, historically, politically or conceptually, and the work must be convincingly positioned within the surrounding architecture. Though the work may have been made for a gallery or editorial context, ideally the images look as if there were meant to be there and we increasingly commission new site-specific works. We aim for a seamless fit within the parameters of the space, so the format of the images must also be right for the context.

Our approach to the selection of new sites is always changing as well. This year we have three projects that are transient and don’t have specific identifiable locations. The project by #Dysturb—a collective of photojournalists that bring current, international news stories to the streets, will be in the Chinatown/Kensington market area, an extremely vibrant and diverse neighbourhood and an ideal setting to stimulate conversations on the street. #Dysturb wheat pastes their large format, black and white images onto city walls, gorilla style, and each image is captioned with descriptive text. The photographs will be highly visible to pedestrians and provide unexpected confrontations with challenging subjects.

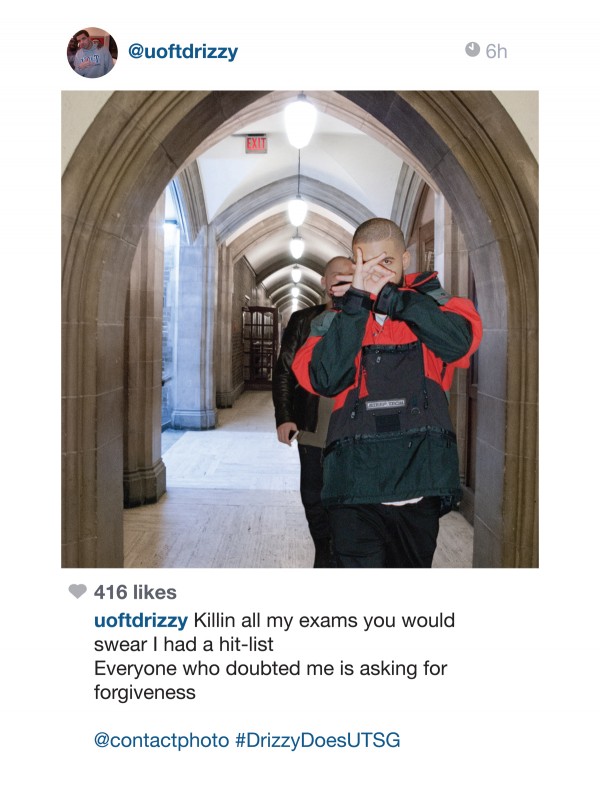

Then there’s the UofT Drizzy poster campaign on the St George campus, which is derived from an anonymous Instagram account. A virtual form of communication is presented in print form. The project bridges two highly relevant methods of spreading the word about social events and celebrity culture throughout the university.

The third is a roaming installation by Jeff Bierk, produced in collaboration with “Jimmy” James Evans, and Carl Lance Bonnici. Jeff is a former “street photographer” whose process of exploring homelessness now involves an ongoing collaboration with his close friends and their community of people relegated to the alleys. Life-size images of his friends sleeping or laying down have been printed on fleece blankets and will be used by them in the Annex area and around Queen and Church. The blankets provide both practical comfort for Bierk’s collaborators and a method of performance that will be posted on Instagram (@jeffari).

IA: Can you tell us more about the #Dysturb installation planned for Kensington market and the Stopping Point installation at the Globe and Mail building? Both are showcasing journalistic imagery and platforms for dissemination. Neither of the photographs were initially created as works of art. How does the festival re-contextualize these documentary images?

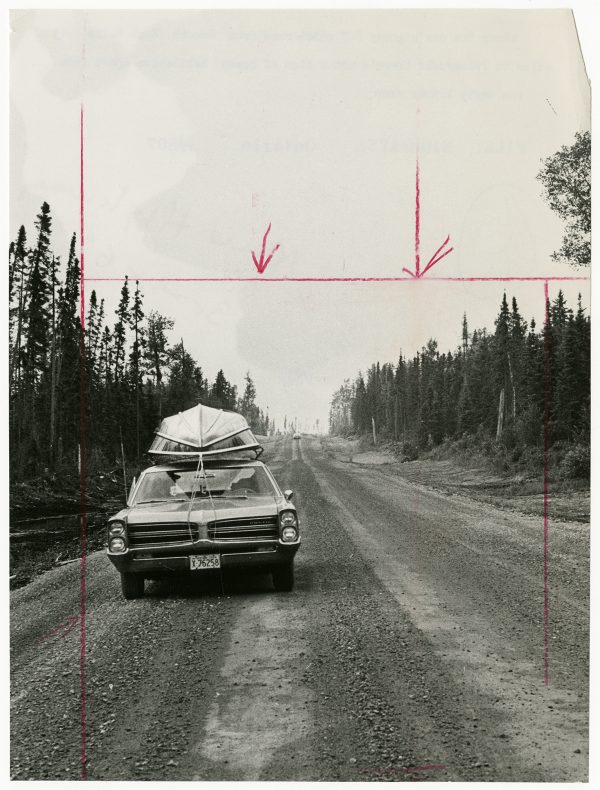

BR: That’s a really interesting parallel. The projects were conceived quite separately but raise some similar issues. With #Dysturb the group deliberately takes their work outside of the traditional news platforms, while Stopping Point comes out of a newspaper photo archive that has been donated to the National Gallery Gallery of Canada. Commissioned in the 1960’s to illustrate the opening of a new secondary highway in Northeastern Ontario, the archival image with grease pen markings exposing the intervention of editors is blown up to massive proportions on the façade of the newspaper’s former press hall. Both projects speak to the fate newspaper photography and simultaneously reveal how shifting context and scale has major implications.

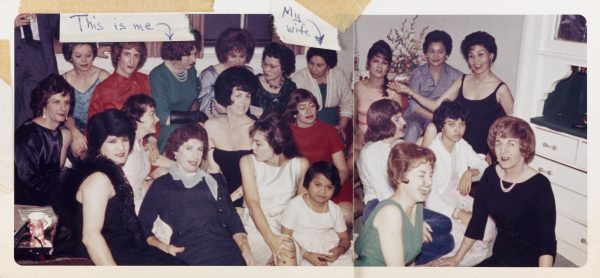

IA: I also wanted to ask about the Casa Susanna installation at St. Patrick Station. Why did you choose to install these personal images drawn from a “queer archive” on a highly public subway platform? Does the subway allow you to reach a broader segment of the population?

BR: The subway platform provides an ideal opportunity to capture the attention of a great number of people as they wait for the train. We have presented projects in the subway many times over the years and at least twice in St. Patrick’s station previously, in collaboration with the Art Gallery of Ontario. Casa Susanna is presented in conjunction with the AGO’s exhibition Outsiders: American Photography and Film, 1950s-1980s, which is just a few minutes walk down the street.

We started with the desire to do a project at St. Patrick station again – the AGO is one of the festivals main hubs this year — and our conversations about the possibilities led to the connection between the underground and the sub-culture represented in these images. Also, the proximity to the courts of law sheds light on past and present injustices. Until recently, anti-cross dressing laws were widespread. While these images may be controversial in the public sphere, presented within the context of the AGO’s collection this is a vital occasion for us to contribute to queer and trans visibility.

MF: What role does the festival play in supporting pubic art?

BR: We support the production of all the public installations we are involved in. While some projects are partnerships, where there is a shared financial responsibility, we usually work directly with the artists and curators to facilitate their work. Many projects would otherwise not have been possible. Sarah Anne Johnson is a good example; she certainly did not previously imagine an opportunity to make a massive work like the one on Bay St.

IA: I would also argue that the festivals in Toronto – CONTACT, Nuit Blanche — are bearing most of the responsibility for supporting temporary public art in the city. In many other cities there are independent associations that play this role, such as Creative Time in New York or Artangel in London.

BR: We’re very glad to have that role and extremely grateful. The program provides incredible opportunities to work with great artists and curators to develop an engagement with art throughout the city and transform everyday activity in public space. The other night while installing Edgar Leciejewski’s project at North York Centre I noticed a young boy and elderly man looking intently at the murals of birds floating in the space. They read the descriptive text on our signage and then engaged in what looked like very thoughtful conversation. I immediately felt that these two people made the weight of our enormous responsibilities feel light as air.

The Scotiabank CONTACT Photography Festival launches on April 27th, 2016 and runs throughout month of May in various locations across the Toronto. For a full listing of exhibitions and events visit: http://scotiabankcontactphoto.com/

Ilana Altman is a curator, designer and editor based in Toronto and founder of The Artful City initiative. Melanie Fasche is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Martin Prosperity Institute at the University of Toronto.

The Artful City is a bi-weekly blog series exploring the evolution of public art and its role in the transformation of Toronto, both the city fabric and the community it houses. For more information about The Artful City visit: www.theartfulcity.org