Lenton Williams worked in the printing department at Eaton’s department store. On the evening of June 14, 1905, the 60-year-old was jogging south along Clinton Street to catch a streetcar at College Street.

As he stepped into the street, a strange thing happened; an automobile driven by H. D. Smith, an employee of local real estate broker Frederick Robins, struck him firmly on his right side, knocking him to the ground.

Bystanders rushed to Williams’ aid and carried him unconscious to the home of a nearby doctor. His chest was bruised and there were numerous superficial cuts to his body, but a closer examination revealed the base of his skull had also been fractured in the collision.

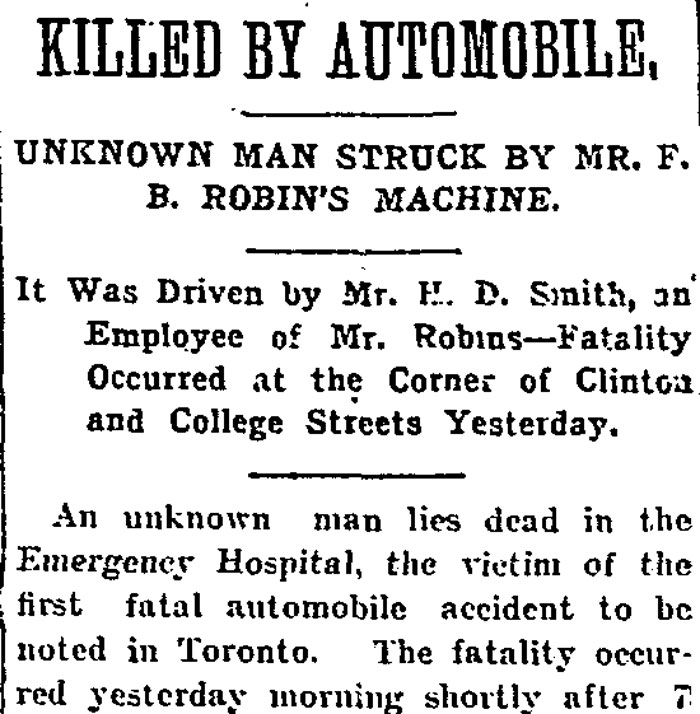

The temporarily unidentified man died a short time later in the city’s Emergency Hospital without regaining consciousness. His death was recorded as the city’s first fatal automobile accident by the Globe newspaper.

At the time, the deaths of pedestrians across the continent were still rare enough to warrant coverage from out of town newspapers. Toronto newspapers covered fatalities in New York City, for example. Williams death was the first of its kind at home, and the police reaction was unusual by modern standards.

Firstly, Smith, the driver, was allowed to continue his journey to Hamilton after striking Williams. Though the Globe described him as “greatly excited” by the incident, it wasn’t immediately deemed necessary to detain him. Authorities later changed their mind and ordered his arrest in Hamilton, but the automobile’s owner intervened and convinced police to stand down.

At an inquest held the next day, a coroner’s jury returned a verdict of accidental death. Witnesses said the auto had been traveling at a “moderate” speed and Smith had been sounding the horn for half a block prior to the collision.

Speed still may have been a factor in Williams’ death. Automobiles of the era were capable of reaching speeds of around 60 km/h. Evidence presented at the inquest showed Smith’s car was stationary about half a metre after the collision, suggesting the driver may have already been braking when contact occurred.

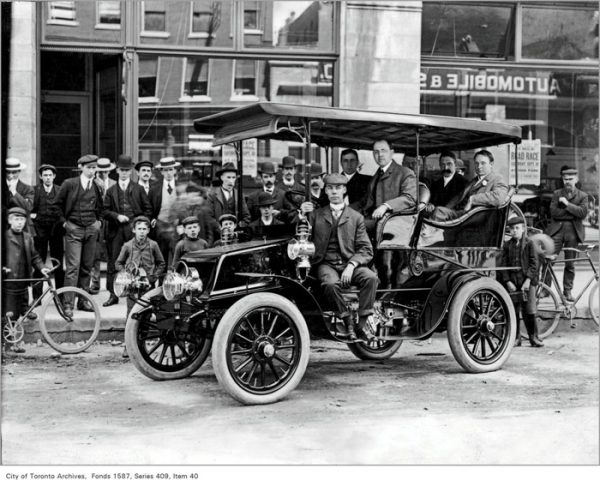

Based on witness accounts, it appears Williams entered the road to board the streetcar, saw the automobile, but was unable to hop back up the curb in time. It can reasonably be assumed he never expected to encounter a motorized vehicle at all. In 1905, autos were still a rare and controversial plaything of the wealthy.

It’s for that reason famous names tend to turn up in reports of automobile incidents. The region’s first speeding ticket was given to Cawthra Mulock, a well-known Toronto philanthropist and businessman, who was caught traveling at more than 60 km/h in Richmond Hill.

A driver employed by Ambrose Small, a theatre impresario who would later disappear under mysterious (and still unresolved) circumstances, was responsible for the city’s second auto death in September, 1906.

Just three blocks east of where Lenton Williams died, 45-year-old Jane Porter was hit at the intersection of College and Palmerston. The automobile, en route to High Park and traveling at around 15 km/h, ran over Porter and dragged her for several metres.

Porter was sitting on the steps of the College Street Baptist Church in the moments before the collision, according to the Globe. She wore a grey skirt, a silk waistcoat under a waterproof overcoat, and a white straw hat with a black-and-white spotted veil.

According to witnesses, Porter stepped into the road and proceeded to cross, unaware of the approaching automobile.

“The front wheels passed over her body, and her feet were caught between the spokes of the wheels, dragging her along until the machine was stopped a few yards from where the accident occurred,” the Globe grimly reported.

The occupants of the car—chauffeur George Seager, Ambrose Small’s parents, Daniel and Ellen, and Small’s wife, Theresa—attempted to help the mangled woman, but she died at the scene about 15 minutes after the collision. The only clue to her identity was a gold watch engraved with the initials “P. J.” There were $8 in bills and a pair of eye glasses in her chatelaine.

As in the Williams’ incident, the driver was not detained, and once again a coroner’s jury returned a verdict of accidental death.

Just before Porter’s death, Montreal recorded its first pedestrian death caused by an automobile when 47-year-old Antoine Toutant was struck and killed on St. Catharines Street. In that case, however, the driver was found guilty of manslaughter and sentenced to six months in prison.

“Everyone has a right to cross or to walk on a street,” Judge Choquet said in his ruling. “It is no excuse that the pedestrian does not see the vehicle or does not hurry to get out of the way. Unfortunately the law is not applied in Montreal. Every driver acts as if he owned the streets.”

In 1906, the public was still largely of the opinion that streets were for moving people on foot just as much as automobiles and streetcars. “In all cases on the King’s highway the pedestrian has the right of way over vehicles of any sort,” the Globe reminded its readers in an editorial that year.

“It is quite proper to blow a horn or make some other signal to get out of the way, but he may be blind, or deaf, or imbecile, and therefore his failure to get out of the way does not justify the driver who kills or injures him.”

In Toronto, deaths and injuries caused by automobiles became increasingly common. In June, 1907, an out-of-control auto struck three children on Kingston Road near Woodbine Avenue, resulting in numerous broken bones and cuts.

In that case, the driver lost control at the top of the hill near Norway Cemetery and careened towards Queen Street, knocking 14-year-old Harold Baker from his bicycle, and sending 11-year-old Eva Wharfe and her younger brother flying more than 4 metres.

Both Baker’s legs were broken, one seriously enough for doctors to consider amputation, and Eva Wharfe’s back was seriously wounded. A streetcar driver who witnessed the incident estimated the car’s speed to be close to 60 km/h.

A furious Globe editorial published the same day as the Kingston Road incident branded automobiles the “great monster of death” on Toronto’s streets.

“The eventual cure for the mad-speed crank must be the jail.”

2 comments

1905, a pedestrian (when did that word originate?) was killed was big news. By 1916, it would be moved off the front page. By 2016, such a death may not even be mentioned in the news, any news media in fact. How times have changed.

WK – Pedestrian was recorded in 1710 according to dictionary.com This isn’t really surprising: “pedestrian” “equestrian” are similar strains of words, and would have been a sensible way to describe 18th century types of traffic.