1962 was a rough year for kids. In the 12 months between January and December, 20 young people under the age of 14 were killed on Toronto’s streets, and more than 1,700 were injured in incidents involving automobiles.

Among those who lost their lives was 4-year-old Patrick McNally, whose toboggan slid beneath the wheels of a truck in Scarborough, four-year-old Perry Chung, who was struck and killed when he stepped out between parked cars on Phoebe Street, and 9-year-old David Rankin, who was knocked from his bicycle against a concrete curb in North York.

October was the worst month for both adults and children. “We averaged more than one death every two days last October [1961,]” said Sgt. R. M. Johns of the Metropolitan Toronto Police Traffic Safety Bureau. “People just don’t adjust to the early darkness in the fall,” he said.

Johns also pinned the deaths of three children in October, 1961 on the parents’ failure to keep their kids off the streets.

“Children aren’t careless—they’re carefree,” he said.

As they had done in the past, local officials responded to the high number of deaths with public education campaigns.

Inspired by a similar scheme in Detroit in 1946, Toronto mayor Robert Hood Saunders co-created the road safety drive that invented Elmer the Safety Elephant. The anthropomorphic cartoon pachyderm, designed by former Disney artist Charles Thorson, first appeared in the Toronto Telegram newspaper in 1947 and was later adopted by Toronto Police as a mascot.

Fines for jaywalking—failing to cross the street at designated crosswalks, which were officially added to Toronto streets in 1958—were added to local bylaws, and features appeared in local newspapers advising motorists against applying make-up in traffic and driving with dirty headlights.

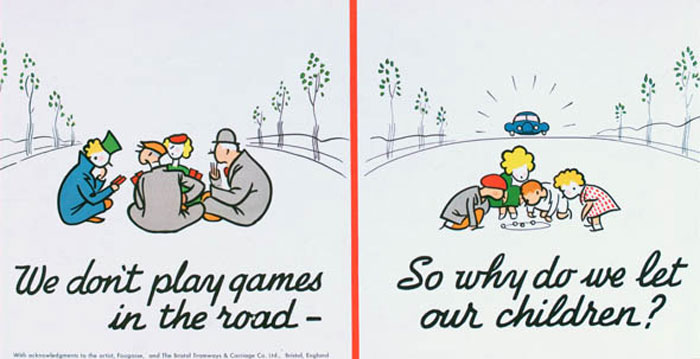

Advertisements posted in TTC streetcars and subway reminded parents to not let their kids play out in the street, but in 1963, Toronto cops hit on a really unusual idea—put kids behind the wheel.

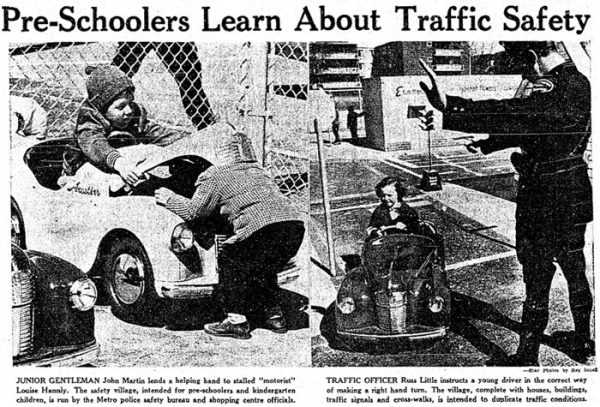

Plans for the Don Mills Safety Village were revealed to the public in February, 1963. A $5,000 model town was to be built in the parking lot of the Don Mills shopping centre. It would include miniature plywood buildings, realistic streets with functioning traffic lights, and little battery-powered cars.

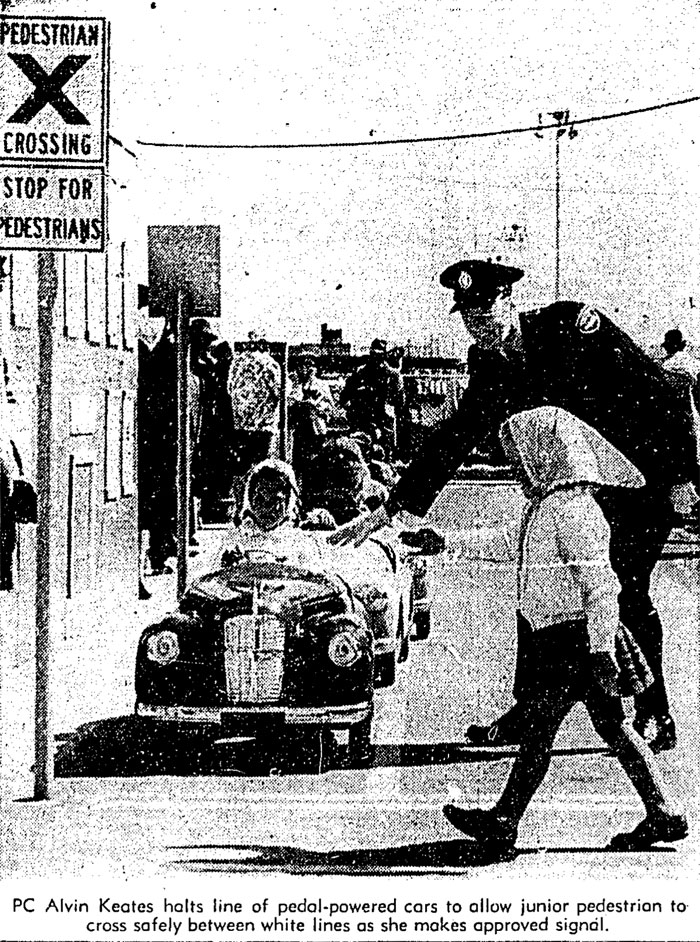

When it opened a few months later, the village consisted of five streets, two houses, eight stores, a service station, bank, schoolhouse, and church. The electric cars were replaced with pedal-powered alternatives, perhaps as a cost saving measure, but no expense was spared on the design of the roads.

The 780 square metre site—touted as the only one of its kind in the country—had functioning crosswalks, stop signs, and almost 200 metres of painted yellow and white roadway.

“No one expects a child to understand all the intricacies of traffic problems,” said Inspector Charles Pearsall from the Metropolitan Police traffic safety bureau. “But the age they learn to walk is the age they should be getting acquainted with the basic safety rules.”

Kids were taught how to understand basic crossing signals and react in potentially dangerous circumstances. If a ball rolled into the street, for example, officers told the youngsters not to run out after it. The curriculum also included advice on how to safely wait for and board the school bus.

Putting kids at the controls of a pedal car was supposed to illustrate how adult drivers see the street. Photos published in the Toronto Star and Globe and Mail show youngsters lined up in traffic at a red light, navigating turns under guidance, and learning to follow hand signals at intersections while their mothers stood like giants on the sidewalk.

At the end of the hour-long instruction, each of the children received a report card with a rating and notes for the parents on how to improve their child’s knowledge of the street.

Unfortunately, the efforts of the police didn’t immediately decrease the number of road deaths.

The Globe and Mail, which kept track of traffic fatalities throughout the year, put the final toll at 113—a new record by a hair. Ironically, the last death of 1963 was caused by a police cruiser.

51-year-old restauranteur Aaron Borkwitz was struck and killed near King and Spadina by a police officer returning to Scarborough after collecting a breathalyzer kit from downtown.

Numbers gathered since the amalgamated Toronto police forces combined their data in 1957 showed there had been no significant increase or decrease in the number of road deaths, though the number of lives lost compared to the number of vehicles did fall.

In 1957, 2.7 people were killed for every 10,000 vehicles on Toronto’s streets. By 1963, that number had dropped to 1.8 deaths for every 10,000 vehicles.

In 2015, 64 people—38 of them pedestrians—were killed on Toronto’s streets.

The numbers are currently at a five-year high.