Interview by: Ilana Altman

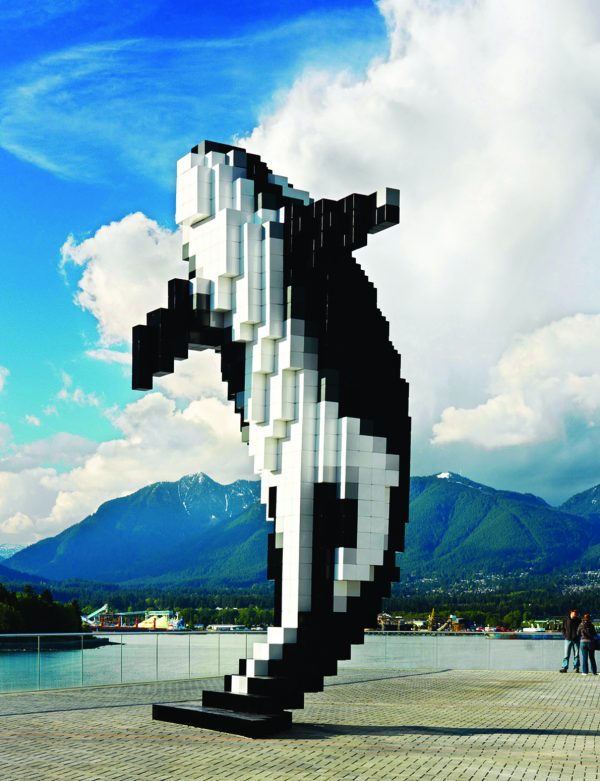

Public Art Management (PAM) is one of Canada’s leading public art consulting firms. They have been actively curating and managing projects across the country for the last 30 years. PAM connects urban developers in both the public and private sectors with internationally renowned artists to create dynamic and lasting public art installations.

We spoke with founder Karen Mills and her son Ben Mills, who serves as PAM’s Vice President. Collectively, they describe the evolving role of the public art consultant and some of their most challenging and rewarding projects to date.

Ilana Altman: Public Art Management has been curating and supervising the development and implementation of public art across Canada for 30 years. How did you first become involved in the field of public art?

Karen Mills: Through attending a fundraising dinner for young farmers as part of the Royal Winter Fair. Really. I went with my business partner Robin Anthony and we joined Shawna Gundy at a table and started talking about a whole range of things. Shawna had been asked to prepare a public art proposal for Metro Hall and asked us to help her (Robin and I were working with corporate collectors then). We spent a lot of time doing research and actually made the final three, but did not win the contract. I however, felt I had found my calling. My dad had been a builder and a foundry man and I spent time on construction sites with him as soon as I could walk. So my passion for art turned into a career centred on working with artists building art. Incredibly lucky really.

Ben Mills: I always loved going on site with Karen as a kid as there were big machines around and they were “building stuff”, but at that time the gallery and museum side of the “art world” wasn’t really up my alley. After graduating university I pursued a different career path, but a few years in I wasn’t feeling motivated or fulfilled. At the same time, and ever since I was about 18, I collected art – mostly prints and photos and art books which piqued my interest – mostly work that would be considered “Outsider” or “DIY”. Whenever I came across an artist I thought was interesting or had ideas that I thought could be translated to an urban scale environment I would pass this information along to Karen to get her opinion based on her many years of experience. Over the years, some of these artists ended up being considered for public art competitions, several of them were awarded public art commissions and with a couple of these projects, I started assisting on a part-time basis in order to learn the ropes. I eventually made the career switch and it was the best decision of my life.

IA: How has the public art landscape in Canada changed over the last 30 years?

KM: When asked what I did, most people said, “What is public art?” Now they ask about the projects we have done. There is an extraordinary interest in the work — not just from artists and the public, but from fabricators and trades that work on the construction and installation of these things. I feel very happy about that because it is a story about boosting the economy through good jobs for artists and many building, fabrication and construction trades — engineers, crane operators, stone suppliers, specialty metal fabricators – even folks who build boats have been involved in projects.

IA: Can you describe the role of the public art consultant? How does it change from project to project?

KM: Someone once called us the lynch-pin of a project. We are dedicated to seeing a project through, so once we have completed the public art planning process and managed the selection process, we are involved in contracts, helping find and work with fabricators, engineering teams, design teams and the clients. We have to watch for any potential problems and try to flag them in a timely way. Sometimes projects run smoothly and occasionally they do not. The most important thing is to be a good communicator, be patient and be firm when needed. We can be mom one day and your high school principal the next.

BM: We’re also there to inform and educate our clients. All clients have varying degrees of understanding of what contemporary art is and can be. Our job is to show them what can feasibly be done in order to get the best possible outcome for the project and the surrounding community.

IA: You have worked extensively in both Toronto and Vancouver, making significant contributions to each city’s public art portfolio. How has your experience in each city differed?

KM: Boy that is a tough question. Every project has expected ups and downs. In both cities we have been so fortunate to work with amazing city staff — people on the other side of the table but with the same interests. Well informed and committed. Red tape in Vancouver is a lot easier to get around though. In Toronto, there is less red tape.

One big difference is in the initiation of city sponsored projects for local and regional artists. Vancouver through their Culture Office are very strong in initiating temporary and longer term projects that nurture young artists. We try to introduce mentorships whenever we can, but I would be happy to see more projects — especially a temporary art program (say installations from 6 months to a year) promoted by the City here in Toronto. We have an obligation to pass on knowledge for future generations. I even think anonymous competitions have a place, just to open the opportunities to a wider audience.

BM: And on the technical side of things, in Vancouver, we don’t have to deal with snow, ice, and the drastic temperature fluctuations, which are inherent to Toronto winters.

IA: You have also been responsible for bringing many international artists to Toronto including James Turrell, Roxy Paine, Matt Mullican, Vito Acconci and Anish Kapoor. In your opinion, what is the value of bringing this international perspective to Toronto?

KM: Global city. Global art. By the way, your list is missing women!! We brought Jackie Ferrara to Toronto for Concord Adex — one of the first women working in land art.

BM: One of the most important things Karen has taught me is that we are trying to represent the art of our time, so that means not only working with artists from Toronto or elsewhere in Canada, but also working with artists from abroad. Toronto is a major metropolitan centre and the art should reflect this. We aren’t some cultural backwater, and we deserve the best just like the New York’s, the London’s, the Paris’ and so on of the world. We are also a tremendously diverse city, with communities from all around the globe, and the public art needs to reflect and celebrate this as well.

IA: I’m glad you brought up the issue of diversity. When running competitions for new commissions how do you ensure there is a broad spectrum of artists represented in the selection process?

KM: Open calls for credentials are really important. One of our last calls had some 3000 views with 700 people downloading the package. The results of a call that closed yesterday was quite interesting. For the first time we have a pretty even 50/50 split between men and women applying and we saw a much, much more diverse range of artists applying. It is quite exciting really. About a week ago I ran a workshop for artists who had never applied for public art commissions and we had 92 people who signed in and participated. Alas, we can encourage all we want but it is up to the artist to decide if they are interested in applying for public art projects and then, the client and selection panel make the final decisions.

BM: We also try to engage with artists from various communities and ethnicities through studio visits and speaking with them through various other means. Speaking with them about how the public art process works and how the projects we work on are realized is usually quite helpful, but also by asking them about how they’d approach public art (if they haven’t worked on a public art commission before) and giving them feedback on those ideas also seems to be pretty helpful. Since we’ve worked on so many projects we have a fairly extensive list of “do’s and don’ts” and helping pass on some of that experience and understanding to artists who haven’t worked in the public realm can be beneficial to their practice if they decide to pursue public art projects.

IA: What has been your most challenging project to date?

KM: The Kapoor mountain. It occupied my life for two years. From that I learned to love engineers and to believe that we can always find a solution. I also realized that genius deserves support.

BM: Every project poses different sets of challenges to overcome, but you learn with experience, so it’s hard to pick one. The first project I worked on, with Jose Parla for Concord Adex, was probably the most challenging because it was the first project I worked on start to finish, and I was constantly in fear that I was doing something wrong. Fortunately Jose and Concord were absolute dreams to work with, so looking back at it really wasn’t all that challenging. But the first time you do something is always the hardest.

IA: ARTablet, the large-scale digital and new-media wall commissioned by the Oxford Properties Group is a unique project requiring ongoing curation of the video content. Artists featured to date include: Tracey Emin, David Rokeby, Casey Reas, and Gerhard Mantz. Can you describe the development of this platform? Does this project represent a new model of involvement for the public art consultant?

BM: This project came about because Oxford was interested in commissioning a large media wall in the lobby of 130 Adelaide St West that revolved around art, but they weren’t sure how to go about it. We worked closely with them for over two years developing the idea of the ARTablet (the name came much later on in the process) and creating a platform for art of the moving image that was new, creative, contemporary, and engaging for the public.

To answer the second part of your questions I would say this represents a new branch or avenue for the involvement of a public art consultant. It’s really something we’ve been doing for years with our ongoing clients who have commissioned multiple installations across a number of projects. We want to ensure they are not commissioning the same things over and over nor are looking at the same artists over and over. Both Karen and I take a fairly eclectic approach to collecting and it’s something we try to influence with our clients. “Variety is the spice of life” and a varied collection of public installations by artists of different backgrounds, aesthetics, practices, age, etc… makes for a far more interesting and creative representation of art than a bunch of dead white men on horses.

IA: Public Art Management is committed to documenting the process behind each piece and has commissioned a series of films that offer rare artistic insight. Is there a necessity for more critical consideration of public art? More interpretive content?

KM: We think telling the story of a project through the artists’ own words is valuable and creates a legacy that has meaning and value and allows the public to hear the artists’ voice. I think the first video we ever did with Douglas Coupland is a hoot. And the film with Vito Acconci just starts to convey what an exceptional, wonderful unique fellow he is. Beyond that, art should speak to everyone in its own way — we can interpret it based on our own life experience.

IA: What projects are you currently working on? What can we look forward to from Public Art Management?

KM: We have a call to artists out for two separate hospital projects now. CAMH and the Etobicoke General Hospital expansion project are both really putting me on a steep learning curve about the therapeutic value of art. I am very interested in the whole P3 system of delivering large-scale projects and have been working on an effective and efficient management system to allow artist involvement in these kinds of larger scale infrastructure programs. We also have a couple of gorgeous projects in the production stage. And there is a large public park in North District that is going to have some new faces presented.

BM: In March we installed Toronto-based artist Niall McClelland’s first public art installation at the Biosteel Practice Facility (where the Toronto Raptors train) at the western edge of Exhibition Place. In August, we installed the first permanent public art installation in the world by Los Angeles-based artist Nathan Mabry at 51 East Liberty St in downtown Toronto. We’re also working on Toronto-based artist Jennifer Sciarrino’s first public art installation, which will be located downtown, but that is still a couple of years away from being installed. We’ve got a few other top-secret projects we’re working on as well.

Ilana Altman is a curator, designer and editor based in Toronto and founder of The Artful City initiative. For more information about The Artful City visit: www.theartfulcity.org

The Artful City is a bi-weekly blog series exploring the evolution of public art and its role in the transformation of Toronto, both the city fabric and the community it houses. For more information about The Artful City visit: www.theartfulcity.org @ArtfulCity

One comment

Karen has done a great job with public art in Toronto. Very glad to see that more projects are being done without resorting to the same names (Toronto has at least a dozen Coupland projects) and that big budget opportunties are given to Canadians. The talent is here; all that’s needed is the opportunity and funding. http://www.nu4ya.com