Canadian bike and walking advocates have been working to try to get the federal government to engage with, and provide financial support to, cycling and walking. Even with a supportive government, that goal can be a challenge because active transportation does not fit obviously into the federal government’s transportation mandate (focused on air, ports, and heavy rail) and possibly because the sums needed are almost too modest for the usual size of federal programs.

So it was very interesting to attend a session at the International Transport Forum on “Good national governance for sustainable active mobility,” where activists from three of the most cycling-friendly nations in the world (Denmark, Netherlands and Germany) discussed the value and challenges of getting their national government engaged in cycling issues. While their situations are quite different from Canada’s, there were nonetheless useful insights to be gleaned.

The session kicked off with an international overview that noted the many international agreements signed by national governments that relate to active transportation, including on climate change, sustainable development, the New Urban Agenda, and sustainable mobility. Yet most action on active transportation happens at the local level, leaving a disconnect — a missing middle level of national policies — between these international agreements and local programs.

Such international commitments signed by national governments can provide a lever to get national action, which in turn can encourage and enable local action. Examples cited include Mexico, where bike sharing programs were supported by the national climate fund, and Brazil, where a national urban mobility law (2012) prompted some cities to create cycle plans.

Germany, with its highly federal government structure and strong state governments, was perhaps the closest analogue to Canada’s system of governance at the session. But federal support for active transportation in Germany is even more constrained – its federal government is constitutionally forbidden from spending money in areas of state or local jurisdiction.

The solution lay in identifying other areas of responsibility where it could spend money. One federal initiative was aimed at reducing congestion on federally-controlled highways. A study was initiated that showed that most of that congestion was caused by trips of less than 10 km, which gave an opening for a successful push to get the federal government to fund separated cycle tracks alongside these highways between towns, in order to divert some of these trips to bikes.

This intercity cycle track network also feeds into Germans’ love of cycle tourism, which accounts for 10% of all tourism. This tourism has the beneficial effect of spreading the economic benefits of cycling to rural areas.

The German federal government also has a mandate to fund climate protection, and so is now funneling support for local cycling infrastructure through its climate fund.

Denmark has one of the most cycle-supportive political environments in the world. The Danish presenter emphasized the value of regular affirmative statements on the value of cycling, and leadership by example, on the part of political and social leaders. This visible support maintains the positive environment and generates a vision that crosses the political spectrum and can survive political change.

But even in Denmark, explicit policy leadership from the national government showed its value. In the 1990s, cycling as a percentage of trips started to decline in Denmark for various reasons. This decline was reversed when the national government introduced a national fund for cycling infrastructure in the 2000s, and a national bicycle strategy in 2014. The fund helped expand key cycling infrastructure such as bridges, and the strategy focused on encouraging everyday cycling and creating a new generation of cyclists. Thanks to this national initiative, the share of cycling in transportation is once again increasing.

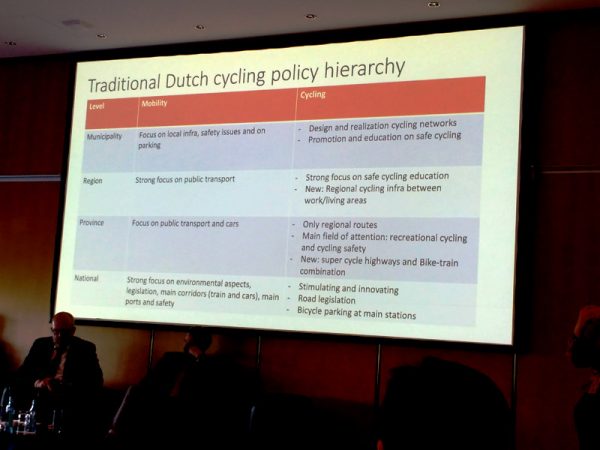

The Netherlands, too, has faced some struggles despite a very positive political climate for cycling. Not long ago, the national government decided to decentralize cycling policy and move responsibility for it more towards local governments. However, it turned out that local governments often did not have sufficient funds for the most intensive cycling projects, such as bridges or massive bike parking facilities near train stations, and the push towards expanding cycling lost momentum. So the national government is now working on a new national plan with targeted goals to increase cycling.

Another role of the national government in the Netherlands is establishing legislation on liability. Under Dutch law, the driver of a motor vehicle is by default liable in any collision with a vulnerable road user – in part because they are in control of the more dangerous vehicle, and in part for the more practical reason that they have insurance (liability can be reversed if the cyclist/pedestrian is proven to have behaved dangerously). As well, cities can be held liable if they failed to act on a piece of dangerous infrastructure that had been subject to complaints and was a cause of a collision. Such national legislation helps to set a standard and overall direction for policy.

While none of these cases are a perfect match for Canada, a few overall lessons stand out. Even if a national government does not have the primary role for cycling infrastructure, it can set a tone that encourages the expansion of cycling through explicit affirmative statements and related legislation. It can find ways to support cycling indirectly through areas where it does have jurisdiction (a recent example in Canada was a failed attempt to enable more railway crossings, including along walk/cycle desire lines, through regulation and funding). These elements can come together in a national strategy that fulfills international commitments and sets an overall vision for the nation.

3 comments

Very interesting. Thanks for reporting on the cycling aspects of the conference.

Great article, agree we must all do better. New Federal Infrastructure money permits and in fact funds cycling and active infrastructure. Issue of capacity building in advocacy capacity and avenues to support partnership models is work to be done.

For example in many cities it’s Business Improvement Areas that enhance pedestrian areas. Allowing these groups to access federal funds may be a way to achieve better infrastructure

What is actually needed is the political will to dedicate a specific percentage of funds to a better bike and pedestrian infrastructure, and the money won’t flow unless it’s done, and to good standards. (In the US, there was a program called ISTEA which might be a model). We have a horrendous set of issues of ward-by-ward bike ‘planning’ when we need a continuous, safe and smooth network vs. patchwork. The City by itself, (at least Caronto), seems completely unable to provide that continuity in a sensible and safe way eg. the Bloor pilot (duplicating Harbord, tho it’s nice to have the domino fall, and better safety in the Annex). The Bloor pilot misses the big gaps west of Ossington and the bit of Bloor St. E between Church and Sherbourne. However the more egregious eg. of how pathetic things are is in Scarborough where the 2001 Bike Plan’s on-road targets are perhaps only 10% done, the off-road being more costly, and completed. Old-style bike lanes of simple lane-line repainting are about $25,000 a km to do, which is relatively reasonable compared to other constructs, and while imperfect etc., at least something would be done.