By Ed Jackson

In June, 2016, U.S. President Barack Obama proclaimed the Stonewall Inn, a gay bar on Christopher Street in New York City, as an American National Historical Monument. The designation was a long-overdue recognition of the Inn’s historic importance. The June 1969 riot by the bar’s working-class patrons which erupted in reaction to police oppression has come to signify the symbolic launch of the modern LGBTQ liberation movement.

Is it time for Toronto to memorialize the location of an equally historic queer protest in this city?

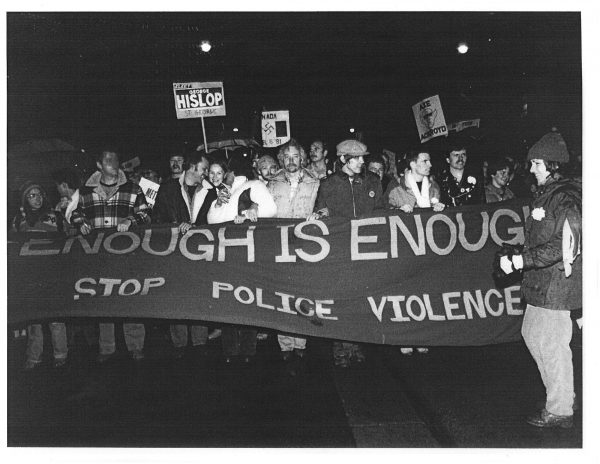

I’m thinking of the spontaneous demonstration on February 6, 1981, which converged at the intersection of Yonge and Wellesley to protest the brutal police raids on five bath houses that occurred the previous night. The protest that night marked a seismic eruption of queer visibility into public space in Toronto, and launched a new chapter in the LGBTQ community’s relationship with the police.

Why does identifying and preserving historical queer sites matter? Many young people growing up continue to struggle as they come to terms with their same-sex attractions and different gender identities. Finding tangible evidence of queer history in a public place can help to affirm their vital connection to a community with an historical past. It is easy to forget that the LGBTQ communities in this city, now so prominent with our June Pride celebrations and corporate rainbow signage, grew out of a marginalized and nearly invisible past often marked by painful and ugly encounters with police and other institutions. As Toronto’s built environment grows and changes at an astonishing rate, there is an increased need to document the historical palimpsest within which its various communities have struggled and survived.

Until the 1970s, some queer men were only able to meet each other while cruising Toronto parks and public washrooms while other men and women made connections in low-key bars and clubs operated by exploitative owners in economically marginal areas.

These spaces played an important part in our history. Bars and clubs have come and gone as the city changed, and the current surge of real estate development is rapidly eradicating these historical meeting places with alarming speed.

One such bar was The Continental, a tough working-class joint in Chinatown at the corner of Dundas and Elizabeth Streets, one of the earliest lesbian bars in Canada. The building has long since been replaced by a non-descript commercial building with a Starbucks.

Another popular gay bar in the 1950s and 60s was Letros Nile Room, at the corner of King and Toronto Streets, the site of popular Halloween balls which drew a curious crowd of straight on-lookers. A developer now has plans to retain the ornate 1886 Renaissance palazzo-styled Quebec Banking building as part of a larger office development, but the building’s historical background is completely silent about its queer past.

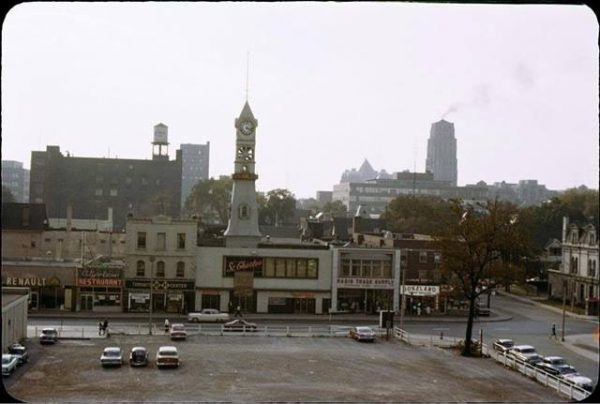

The Halloween balls moved north in the 1960s to the popular St. Charles Tavern, at 480 Yonge St, a former Fire Hall with a striking clock tower (“Meet me under the clock” was the bar’s slogan). Once one of Toronto’s best known gay bars, it closed long ago, replaced by nondescript retail stores. A developer plans to build a large condo on the site, retaining only the tower as a rump reminder of its earlier physical history. This developer has at least highlighted the historical role of St Charles Tavern in promo for the building, perhaps seeing this as a lucrative branding hook for sales.

Both developers should be encouraged to erect prominent historical plaques which include details of their buildings’ queer heritage.

But these are hardly the only places that merit recognition. In the 1970s, LGBTQ activists started organizing newspapers, bookstores, support organizations, churches, communes and protest demonstrations. These were significant places, worthy of memorialization. Here are just a few:

- Community Homophile Association of Toronto, 58 Cecil Street: The city’s first Gay Pride Week, in August 1972, was launched from the steps of this building, now the Cecil St Community Centre, but in its early years variously a protestant church, a synagogue and a Chinese-Catholic centre.

- The Body Politic/Glad Day Books, 4 Kensington Ave. The gay liberation newspaper and the still-surviving gay bookstore shared space in a drafty shed at the rear of 4 Kensington Ave in the early 1970s

- Three Cups of Coffee/Lesbian Organization of Toronto (LOOT), 342 Jarvis St. This space became an important location in the late 70s for several women’s and lesbian organizations, including The Other Woman newspaper and Wages Due Lesbians, the Three of Cups Coffeehouse and the Lesbian Organization of Toronto (LOOT).

- Kentucky Fried Chicken, Wellesley and Church. In July 1983, the AIDS Committee of Toronto, the first HIV organization in Eastern Canada, moved into a run-down second-floor office above this KFC; the building will soon be razed for a major new condo complex at the Church-Wellesley intersection.

- Metropolitan Community Church, 115 Simpson Ave. On Jan 14, 2001, two men and two women became the first same-sex couples to be legally married in Canada. The ceremony was conducted in this church by Rev. Brent Hawkes, under police guard and wearing a bullet-proof vest, having resorted to the rarely used strategy of “publishing the banns of marriage” to make it stick. It took two more years of legal wrangling in the courts for their marriages, along with all subsequent same-sex marriages in Ontario, to become officially recognized by the state.

- Allan Gardens, Carleton, and Sherbourne. As far back as 1882, when the dandy Oscar Wilde lectured on aesthetics there during his North American tour, the Gardens have been a contested queer space. Whether it was men arrested by undercover cops while cruising for sex under the cover of night, or LGBTQ activists launching Pride rallies, Dyke marches or sex worker protests, the Gardens have played a central role in our communities’ changing visibility.

Ontario Heritage Trust and Heritage Toronto are the main organizations that administer historical plaque programs in Toronto. So far, Ontario Heritage Trust has memorialized only one queer heritage site, at University College. In 2011, at the instigation of the Mark Bonham Centre for Sexual Diversity Studies, the Trust erected a plaque honouring the history of sexual diversity activism and the founding of the University of Toronto Homophile Association in 1969, the first organization of its kind in a Canadian university.

Public heritage memorialization costs money and often tends to privilege the history of more establishment figures, often white. Toronto’s LGBTQ communities are racially and culturally diverse, so campaigns to honour queer history sites need to be inclusive of these traditionally marginalized communities.

In fact, to be true to our history, queer public memorialization should include places and events that highlight political activism, sexual transgression and social dissidence. They should honour episodes of resistance and rebellion, as well as more traditional signposts of integration and acceptance.

In line with this thinking, here’s a prediction to consider: A prime candidate for queer public memorialization could eventually be the spot near Yonge and Carlton where the queer and trans members of Black Lives Matter halted the 2016 Pride parade. Although It remains to be seen what lasting social change will result from that protest, no one can deny it was a spectacularly successful use of public space, and has helped shine a light on anti-Black grievances within Pride. It has also helped to demonstrate that, while relations with the police in this city have changed dramatically if you are white and queer, they remain far from resolved for those who are Black or Indigenous as well as queer.

It could eventually rank up there with the bath house raid protests as a turning point — and place — in Toronto’s queer history.

Ed Jackson, a former editor of The Body Politic, is one of the co-editors of the queer Toronto history anthology, Any Other Way: How Toronto Got Queer, published this spring by Coach House Books. Follow him on Twitter: @edjacksonator

One comment

all of the sites mentioned – and many others – are featured in the free locative history app Queerstory. http://www.queertory.ca