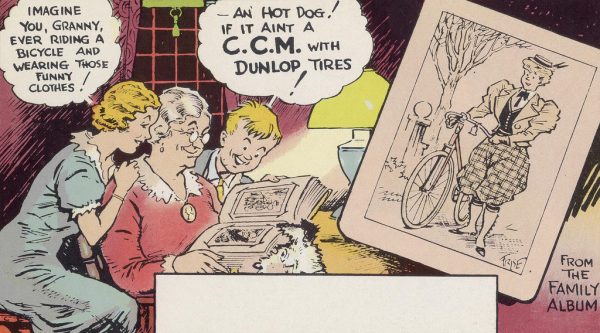

A fun fact to bring up at parties is that cycling helped get women the right to vote. Sort of. At the end of the 19th century, women had been demanding equity for decades, but the public sphere still largely belonged to (white) men. Then came the bicycle, and with it came both independence and community.

Now, women cyclists could visit friends and run errands outside of their immediate neighbourhood without relying on men to escort them, and they could also attend activist meetings on their own. Many women began wearing pants in order to ride more easily, a clothing switch that was both utilitarian and symbolic of how the narrow world of women was beginning to open up to resemble the wider world of men. They faced immense criticism and sometimes violence for daring to act unladylike, but with their greater freedom of movement came a greater ability for women cyclists to meet and rally together in common spaces, take on leadership roles in their communities, and organize for political causes, including voting rights.

Eventually, Susan B. Anthony said, “I think [bicycling] has done more to emancipate women than anything else in the world.”

For me, a century and a half later, my bike has been a lifeline to that same independence and community. I first started riding every day because I couldn’t afford to take transit, and cycling allowed me to say “yes” to dinner invitations, volunteer commitments, and public protests without weighing the cost of a token or cab ride. It was a relief to be able to choose when to leave meetings or parties, even late at night, without relying on someone else to drive, and without fearing the kind of discomfiting and inescapable harassment that I used to face in the closed spaces of the TTC. At one point, amidst news reports of multiple sexual assaults on sidewalks near my workplace, I rode my bike as conscious self defence. It still sometimes feels safer for me to be on the road, on my bike, than anywhere else — and that sense of safety has afforded me the ability to build relationships, explore the city, and become a participating member of society.

Of course, part of the reason I feel so safe on my bike is that I live and work in a part of Toronto that has numerous bike lanes. In my bike-friendly census tract, 19.8% of employed residents bike to work and about half of them are women, according to the 2011 National Household Survey. I think that we can reasonably expect that there are even more cyclists in the area now, six years later. Across the whole city, though, only 2.2% of employed Torontonians bike to work, and women are much less likely to ride than men. While women riding in the 1890s faced their own barriers, they didn’t have to deal with the dangers of fast-moving motorized vehicles that hadn’t yet been invented. Now, for a variety of reasons, women are less likely to ride on streets that don’t separate us from cars, so a lack of safe bike infrastructure poses a huge deterrent to women considering cycling.

What does this mean for our present-day ability to get involved in the public sphere? In parts of our city where bike infrastructure does not exist, it means that many women are not able to choose to bike to visit friends, run errands, or attend activist meetings. And just as 19th-century men often monopolized the family horse, if the family were wealthy enough to own a horse, modern-day men often monopolize the family car, if the family is wealthy enough to own a car. So women lacking both the option to drive and the option to bike must instead consider the cost of a token or cab ride, rely on others to offer a drive, and leave gatherings early in order to avoid nighttime harassment on the bus.

These are real concerns. I can attest that it’s much harder to commit to a volunteer commitment or political campaign without true freedom of movement. It’s much easier to become isolated from friends when leaving the house feels cost-prohibitive or unsafe. In other words, when we as a city do not ensure that Torontonians have reliable and safe forms of transportation across the board, we are effectively blocking many women from participating in public life as fully as men do. More specifically, we are blocking women who lack the wealth and resources to overcome transportation barriers — women whose voices are already vastly underrepresented in our political discussions.

Toronto City Council recently passed a motion supporting a gender equity approach to the City budget. Much of the discussion about gender equity in municipal affairs has focused on important issues surrounding shelter, support and housing, childcare subsidies, and poverty reduction. These City services and programs disproportionately affect women, and it’s an excellent step forward for us to apply a gender informed lens when making decisions about their funding. It is worth considering ways to apply a gender lens to other parts of the budget, too. When we don’t prioritize building safe bike infrastructure across the city, we are denying women equitable access to our public sphere, and Torontonians deserve better.

This Article originally appeared in Spacing’s summer 2017 issue.

This Article originally appeared in Spacing’s summer 2017 issue.

2 comments

Bicyclists requested that streets be paved for a smoother and less dusty ride. Then the automobile came along, demanding even more paved streets, wider streets, and eventually demanding that the streets belong ONLY to the automobile and no one else.

Yes, veliberation. Though I don’t think we need to go to the full extent of ‘only separated bike lanes’ as that’s almost an excuse to just do a few signature/profile projects eg. Bloor pilot for $500,000 vs. all of Bloor/Danforth for the same sum. Paint is a good start, and provide the connected network vs. only bike safety where the Councillor approves of it – and that usually isn’t Ward 18, ironically with a woman Councillor Ms. Bailao, who’s doing some good work on housing, yes.

If there’s an attempt to link biking to the right to vote, puh-lease… especially if there’s no mention of what the Pankhursts and supporters did. Mere rationality didn’t work. In that vein, I’m unsure what a cyclists resistance might look like however – stopping at all stop signs and crosswalks?

More seriously, the place to start for equity is car subsidies. According to an older figure from Vancouver, they calculated every car had a $2700 annual avoided cost/subsidy. vtpi.org may be a good source for updated info on that topic.